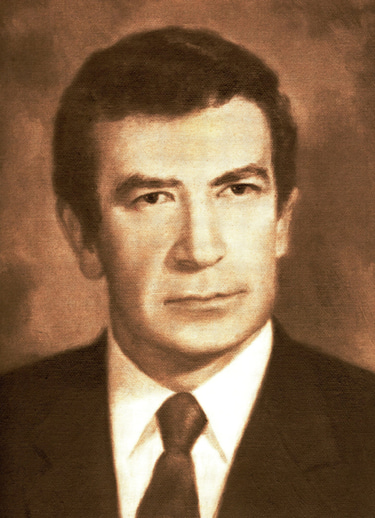

BIOGRAPHY

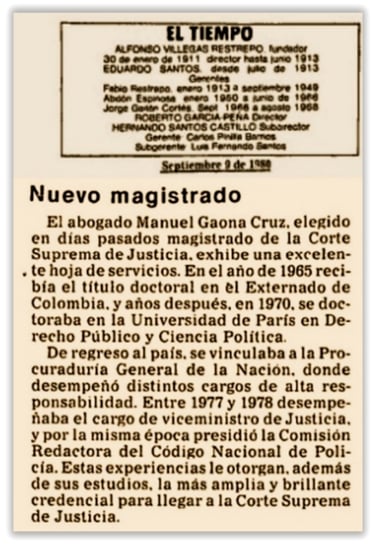

Upon his return to Colombia, the young jurist dedicated himself to teaching and public service. In the words of Colombian Professor Fernando Hinestrosa Forero, Manuel Gaona Cruz's career "was dazzling, swift, as if a premonition were driving him..." (Estudios Constitucionales Manuel Gaona Cruz, MINISTERIO DE JUSTICIA DE COLOMBIA 1988, Tomo II, page 608). Manuel Gaona Cruz served as Assistant Procurator, Advisory Attorney to the Chief of the Public Ministry, Secretary General of the Public Ministry, Constitutional Law Professor at Rosario, Externado and Boyacá Universities and at the General Santander Military School, Director of the Department of Public Law at Externado University, President of Bogota's District University, President of the National Commission for drafting the Police Code, Under Secretary of Justice of Colombia, Supreme Court Justice and Chief Justice of the Constitutional Chamber of the Supreme Court of Colombia. Both his landmark opinions on extradition and international law delivered as Chief Justice and his work on international judicial cooperation as Under Secretary of Justice both in Colombia and in Washington D.C. have been deemed influential in the development of the travaux préparatoires that led to the United Nations Convention Against Illicit Traffic in Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances of 1988.

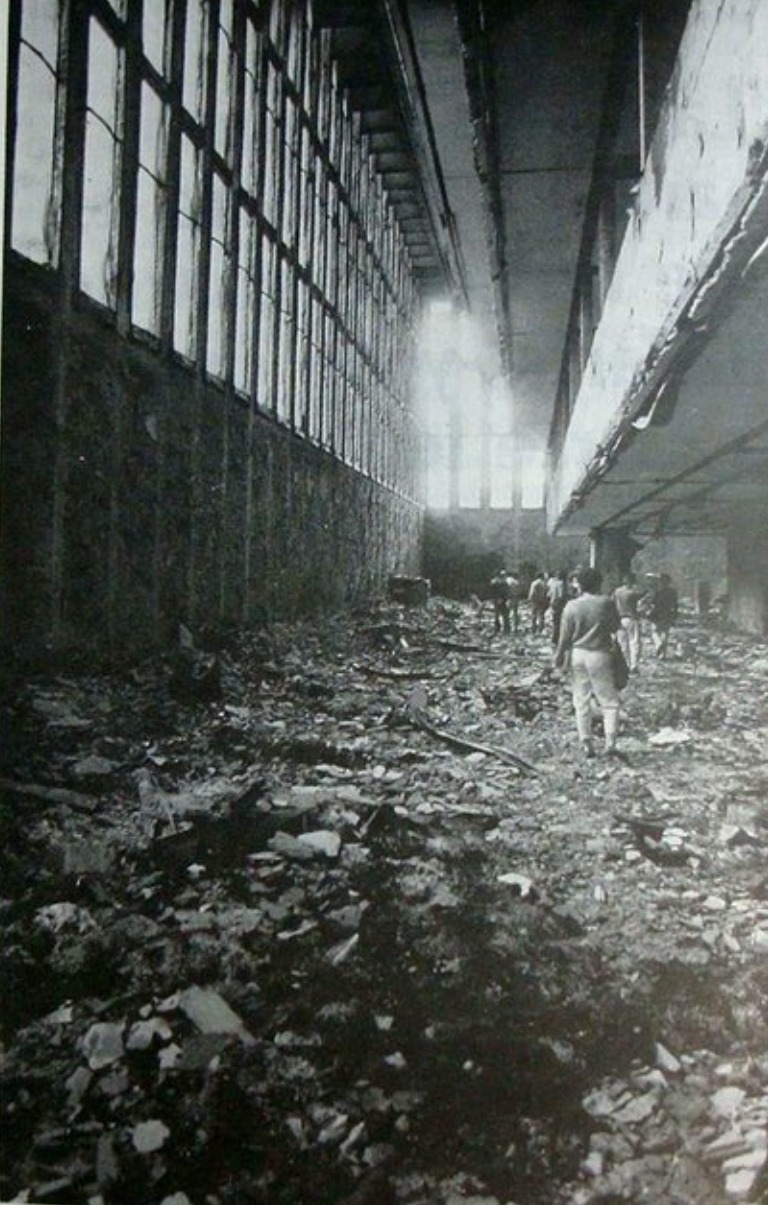

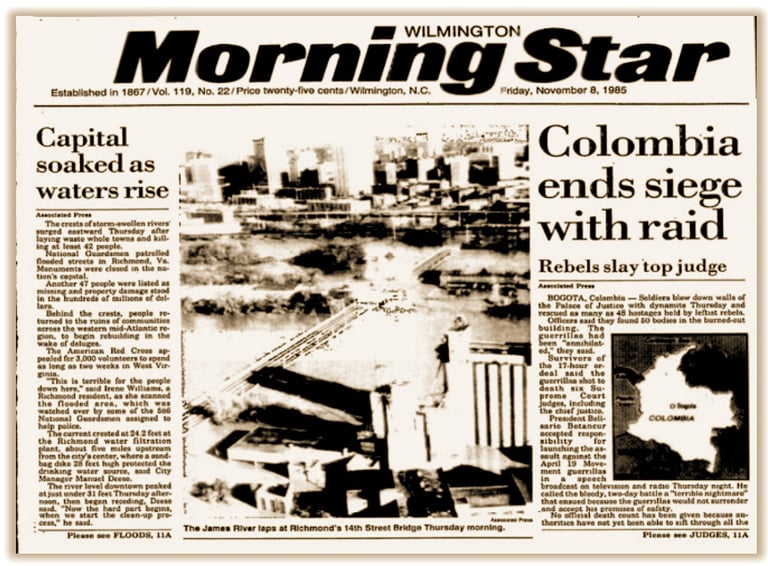

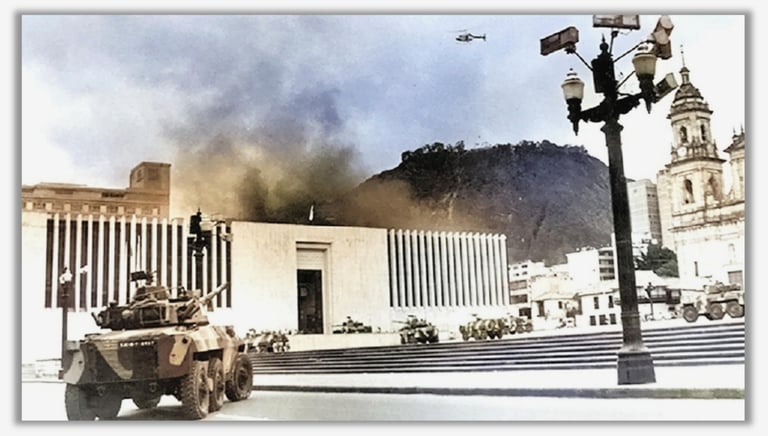

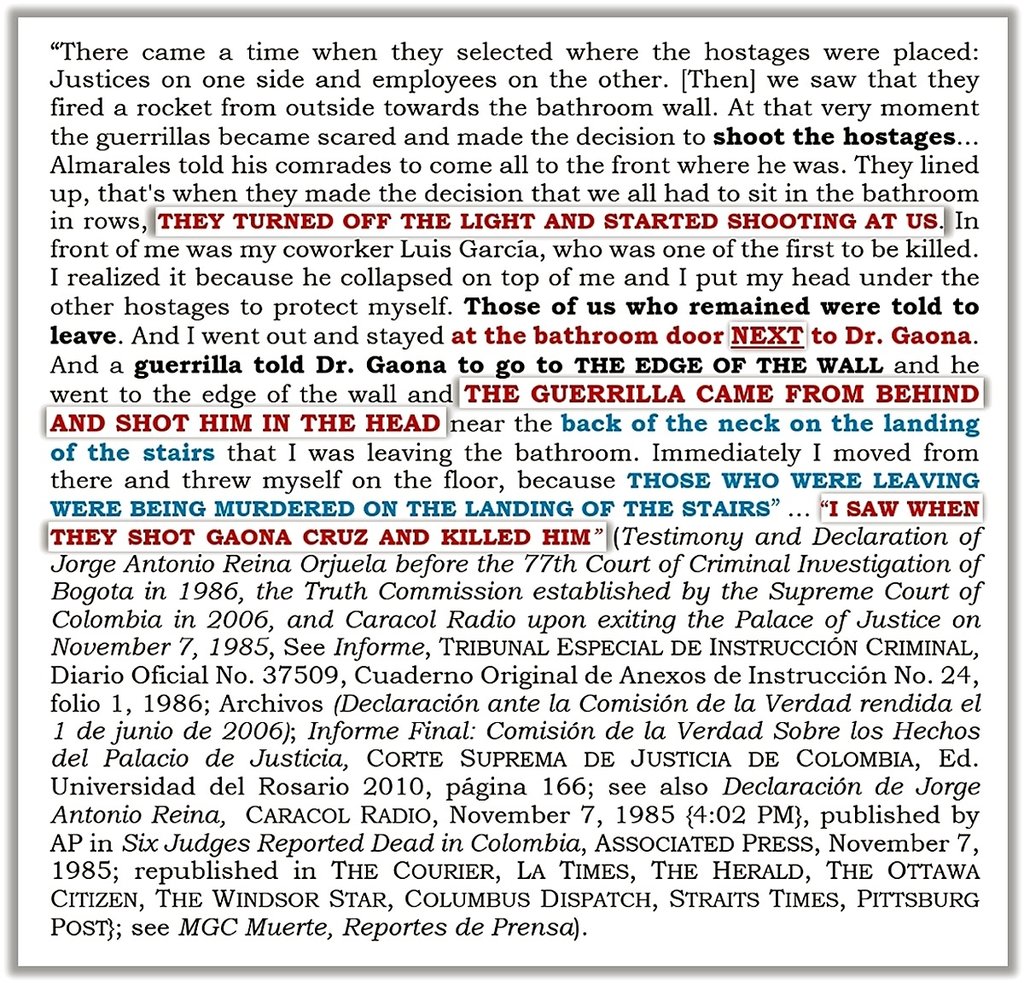

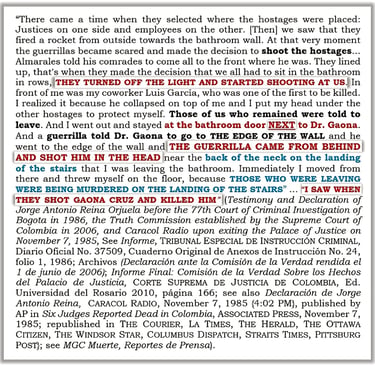

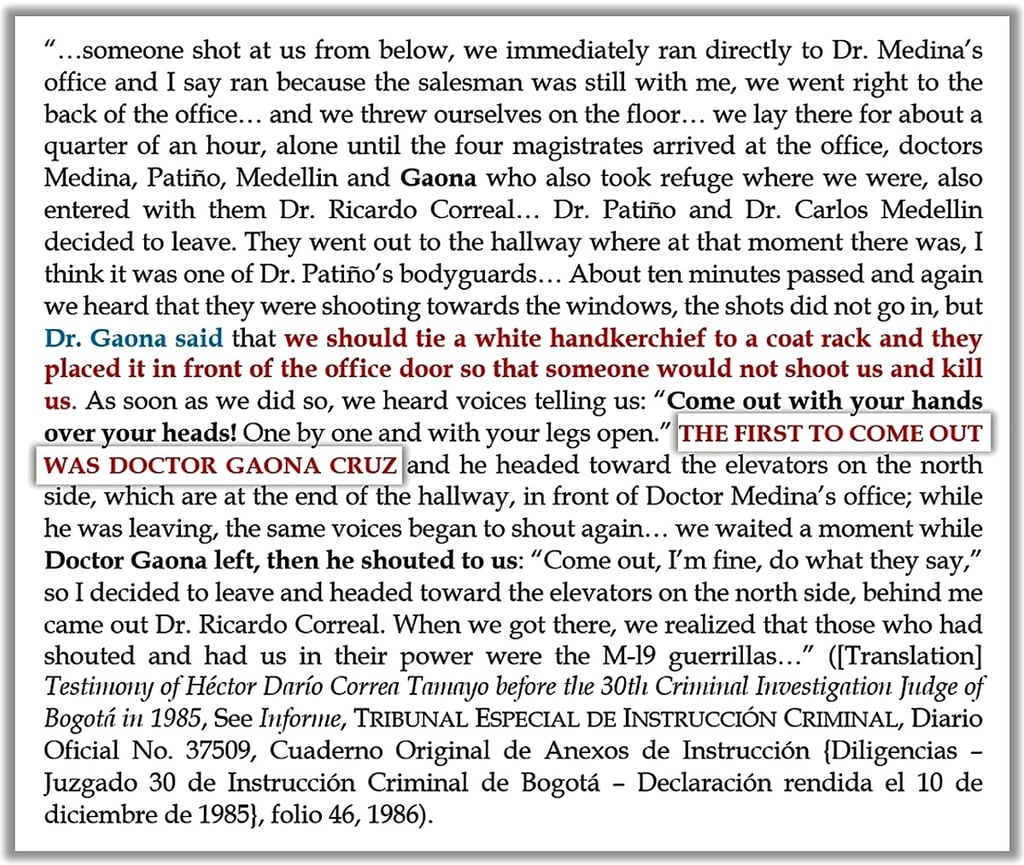

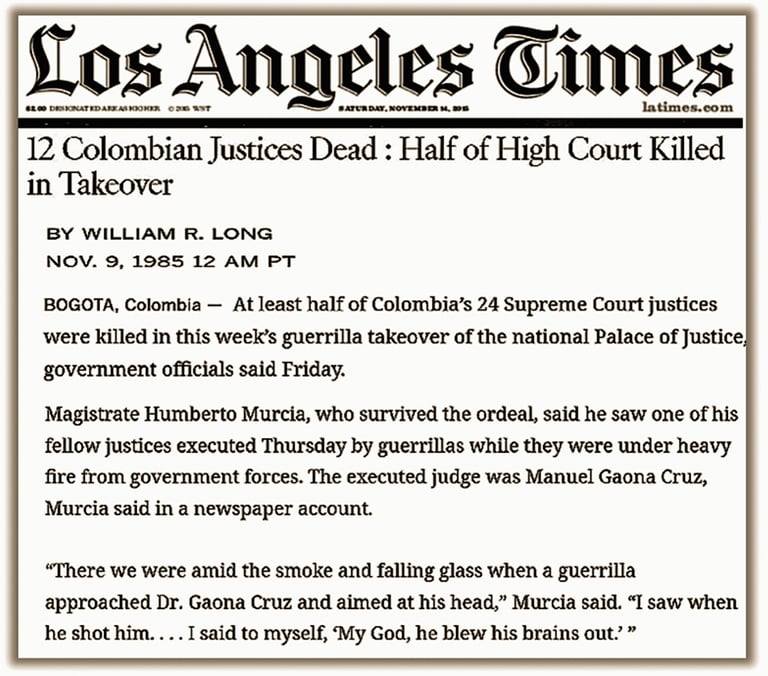

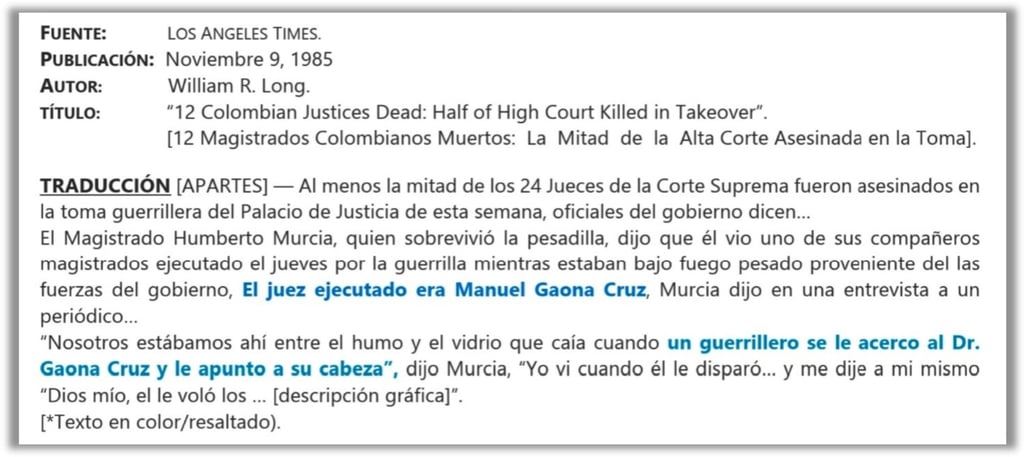

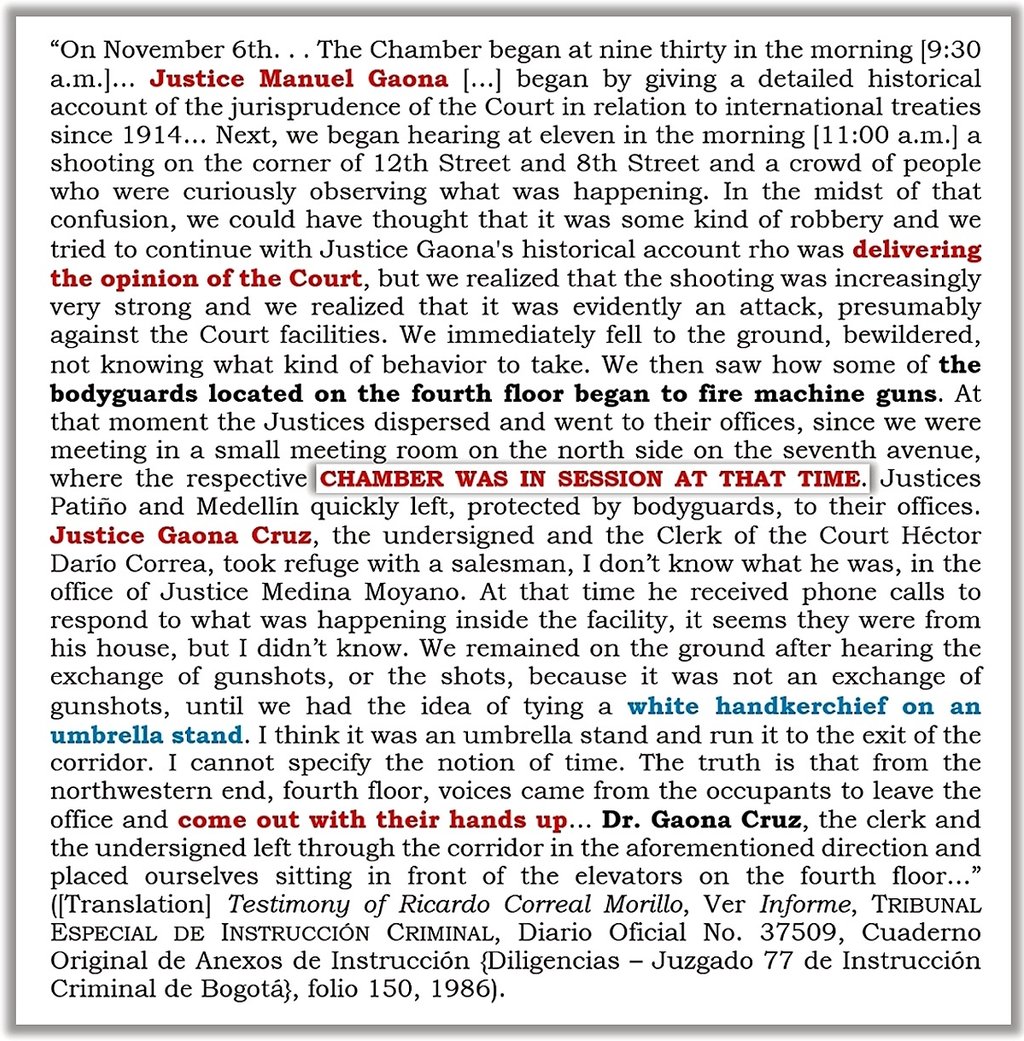

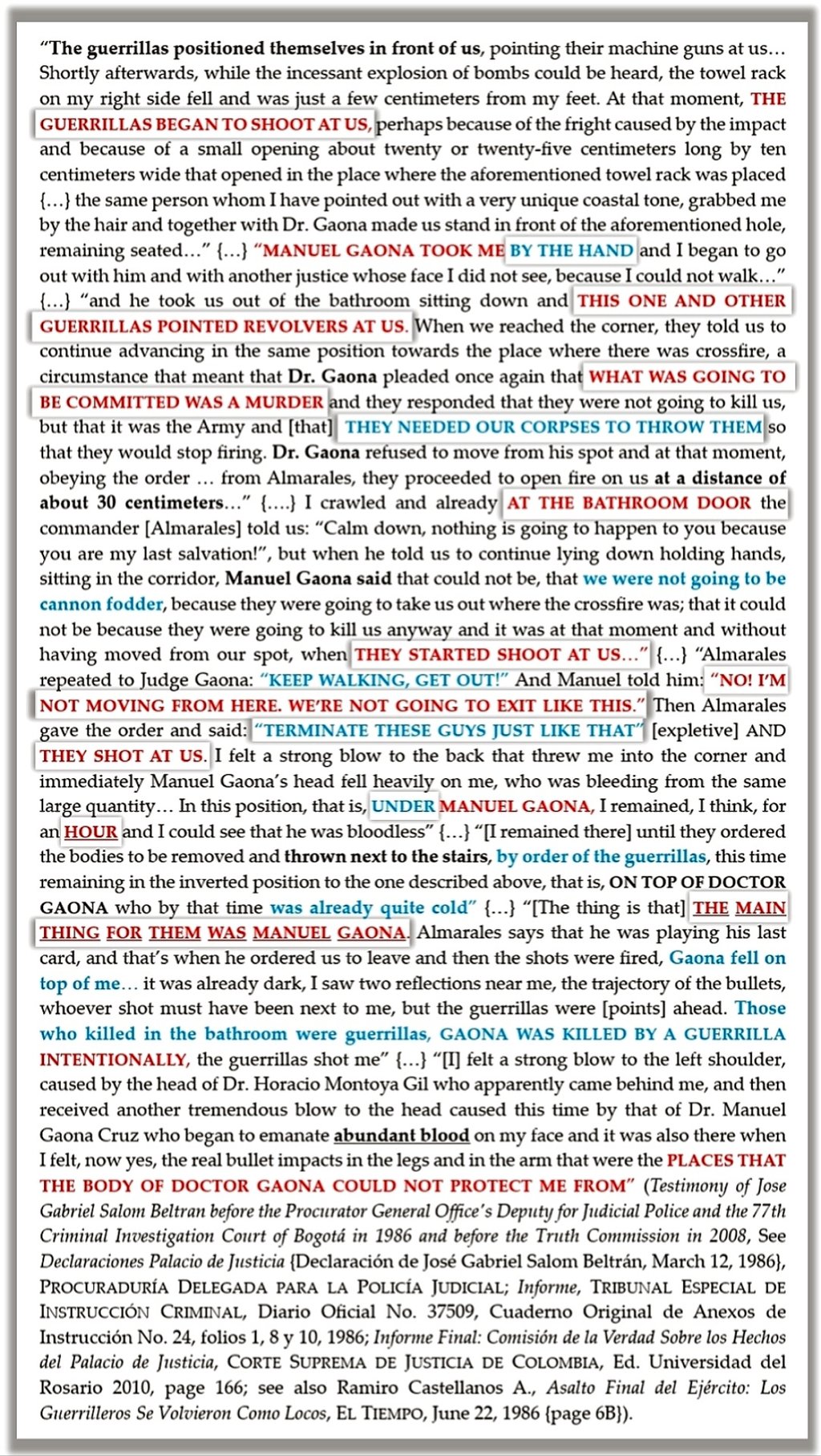

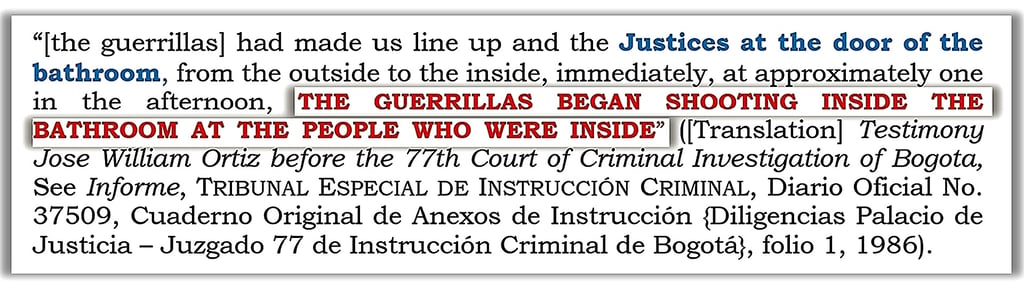

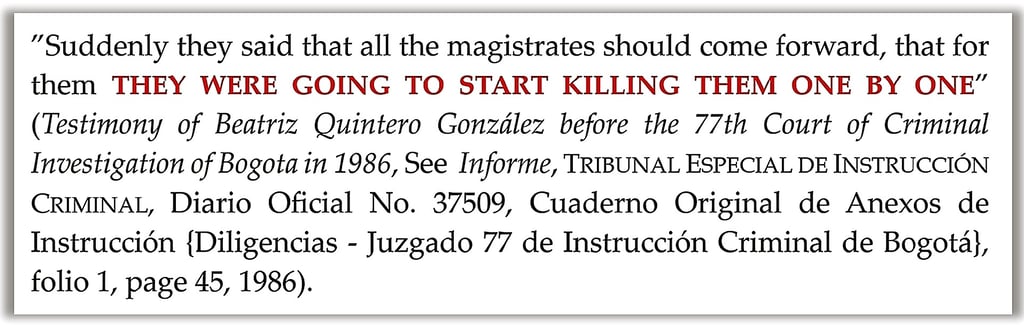

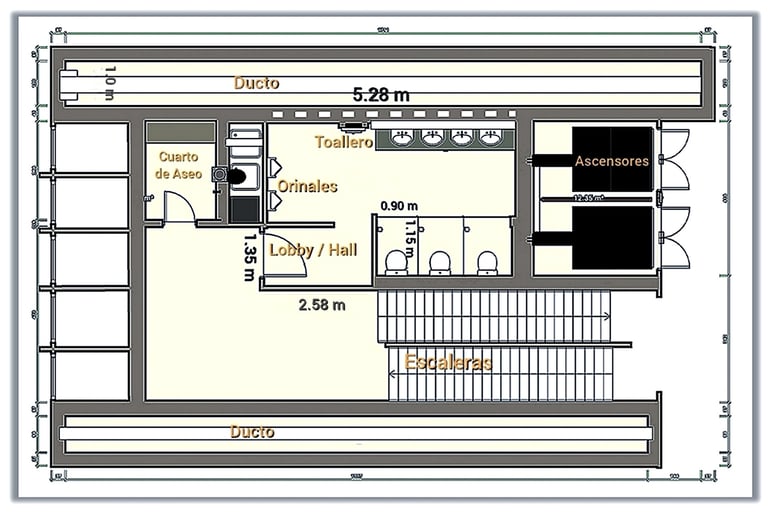

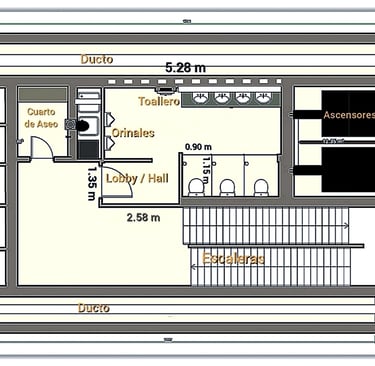

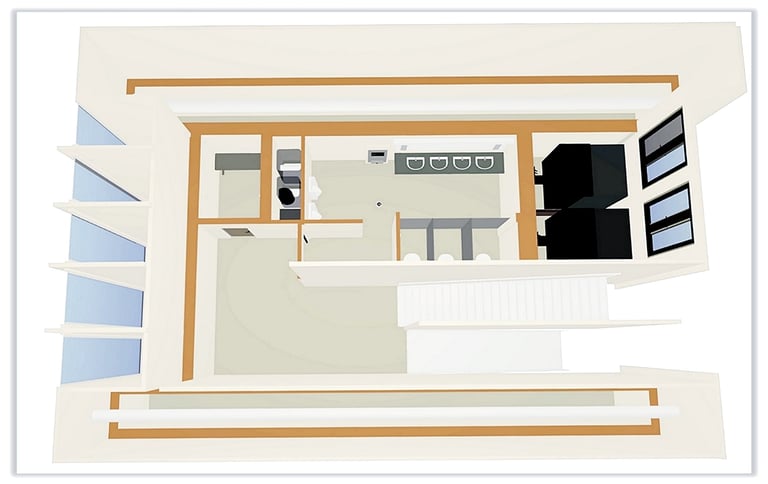

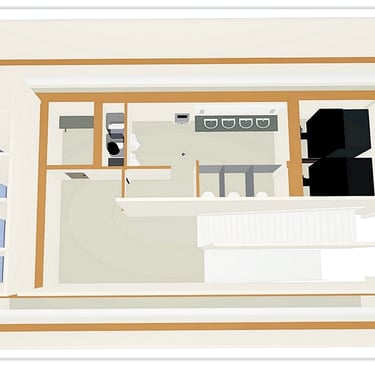

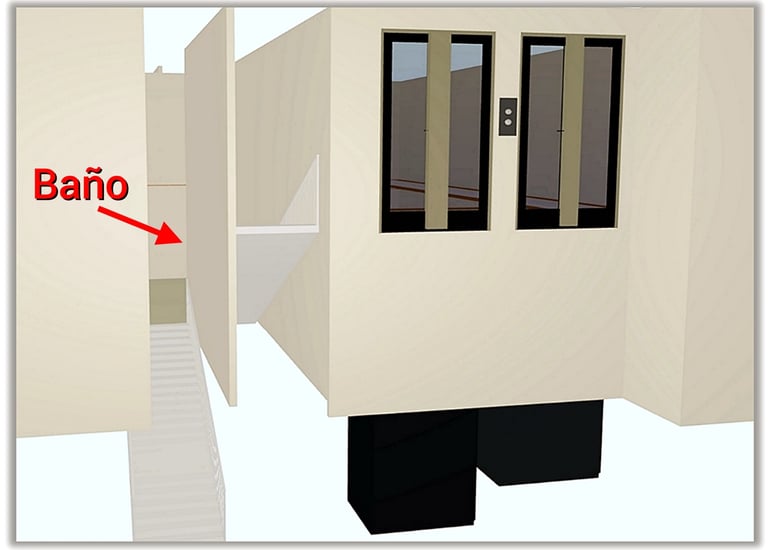

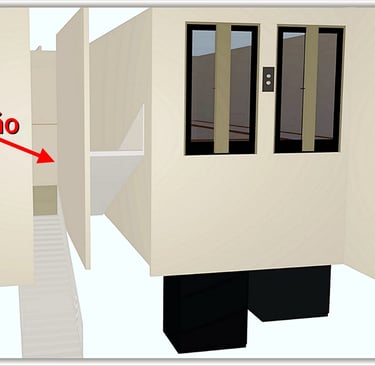

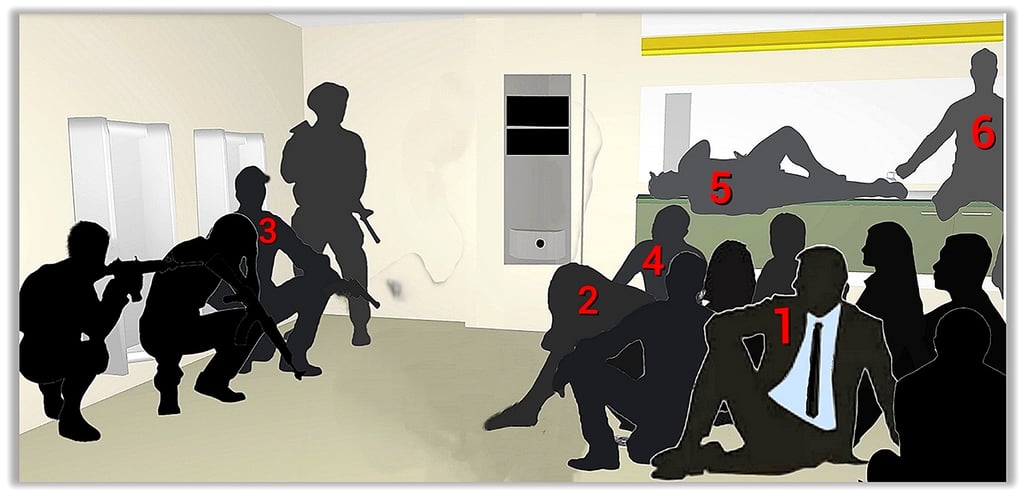

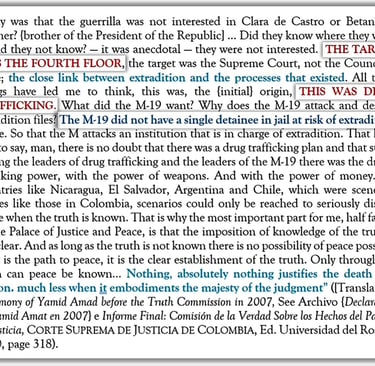

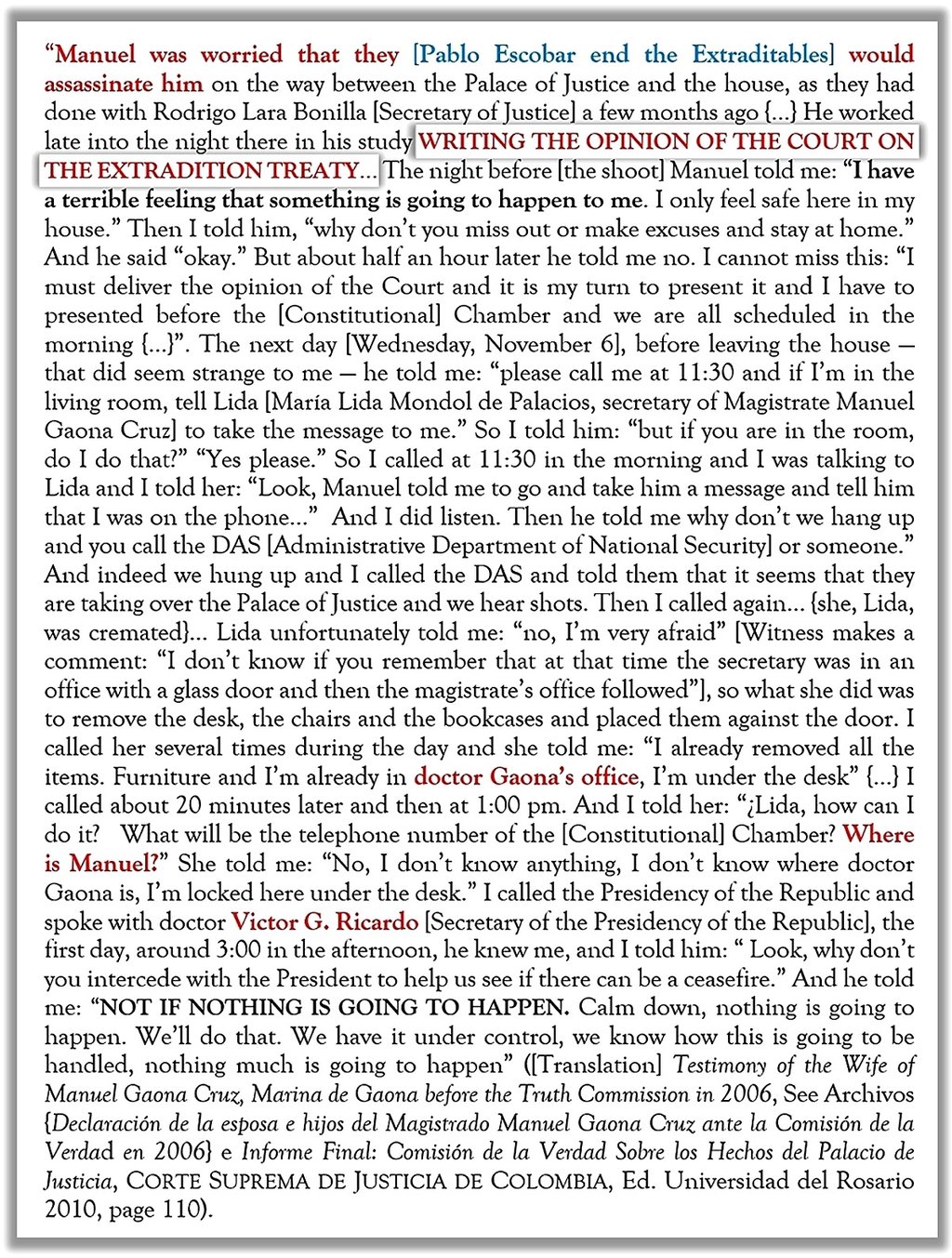

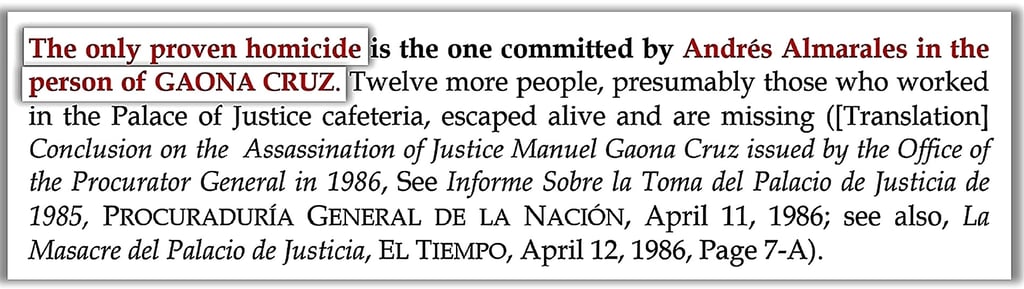

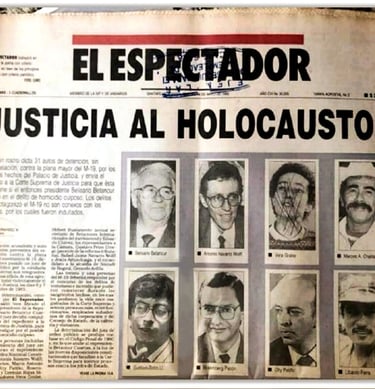

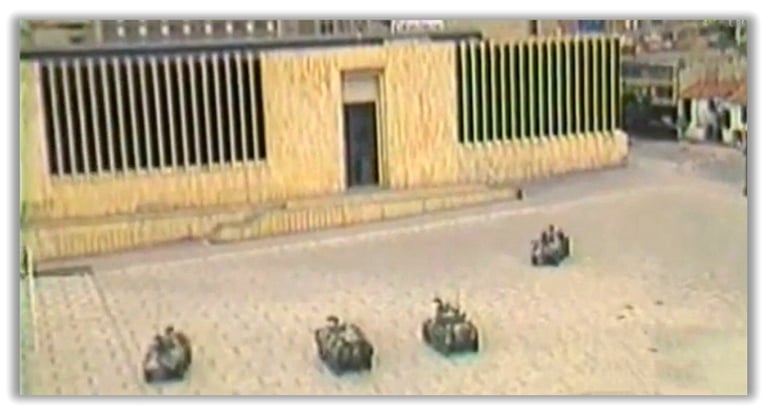

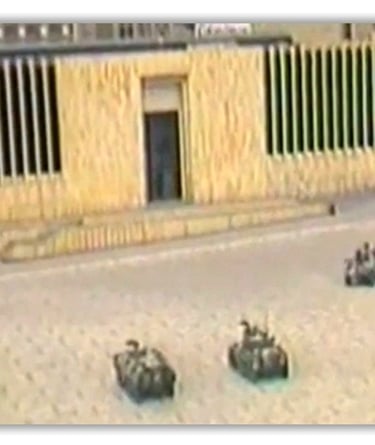

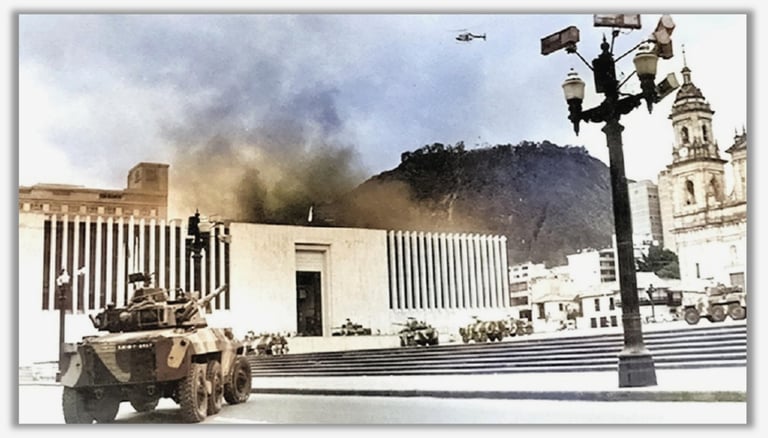

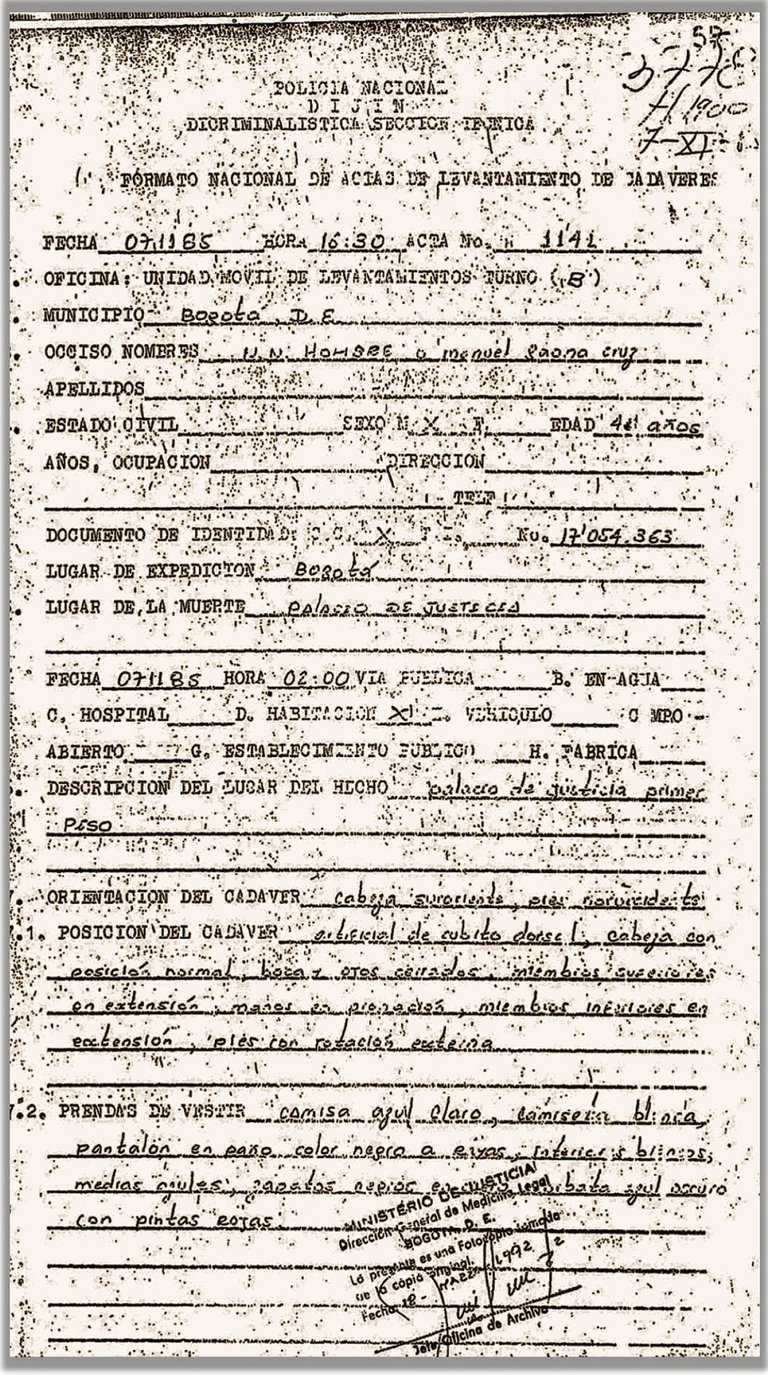

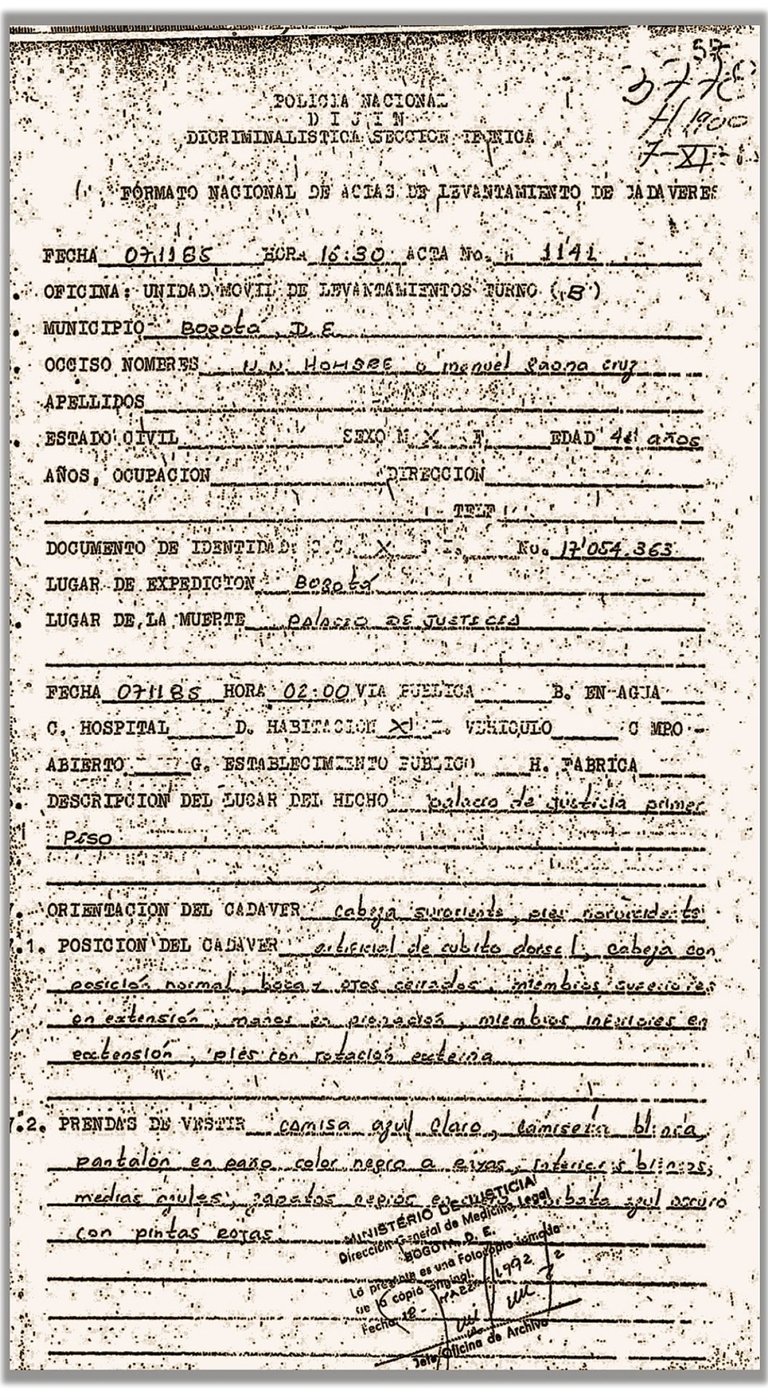

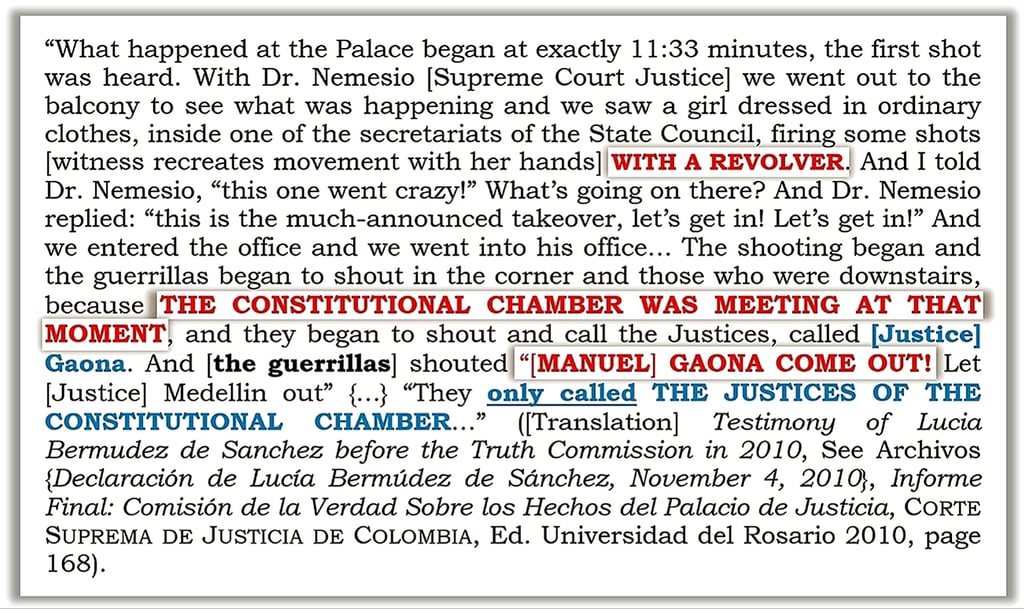

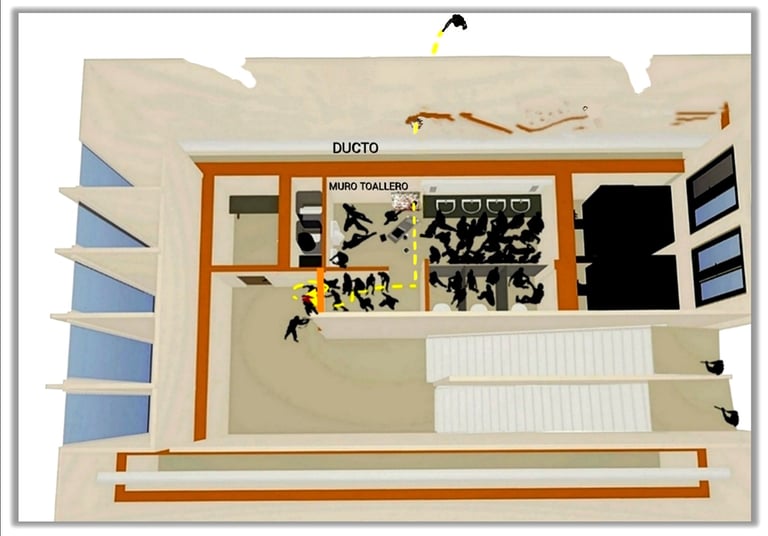

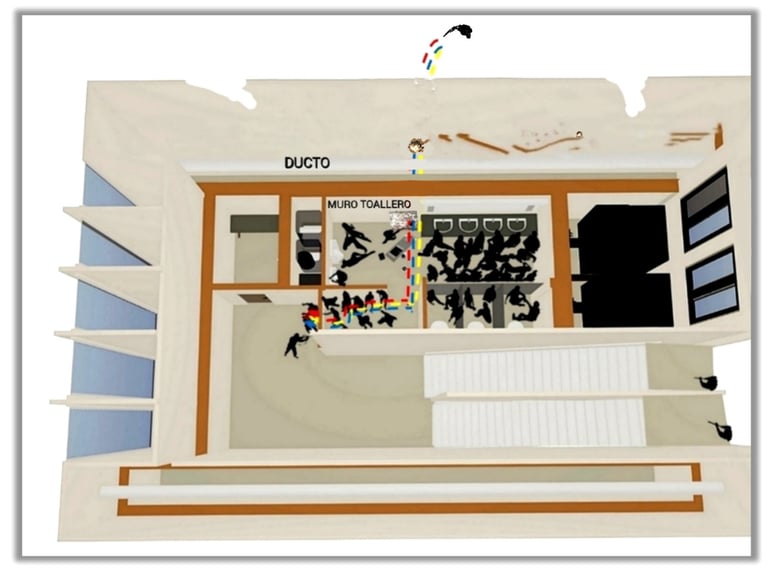

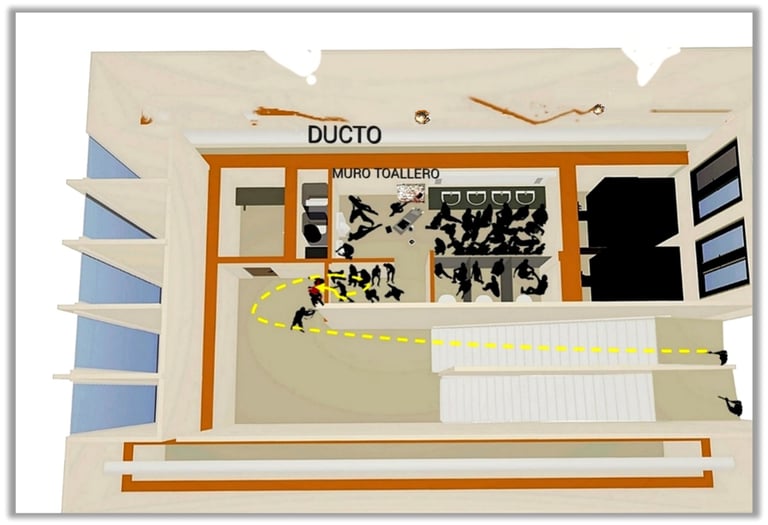

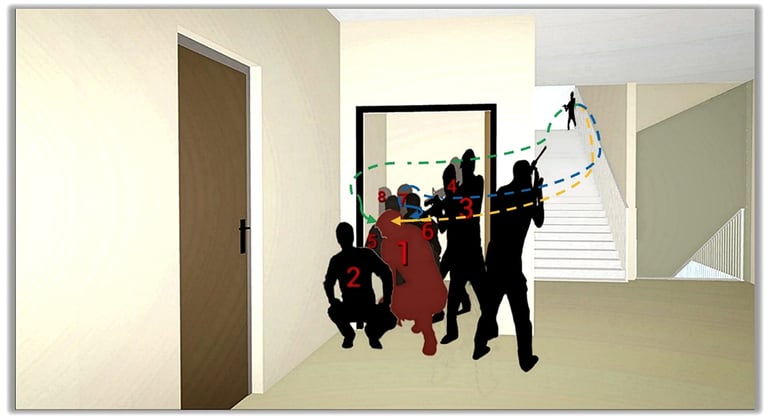

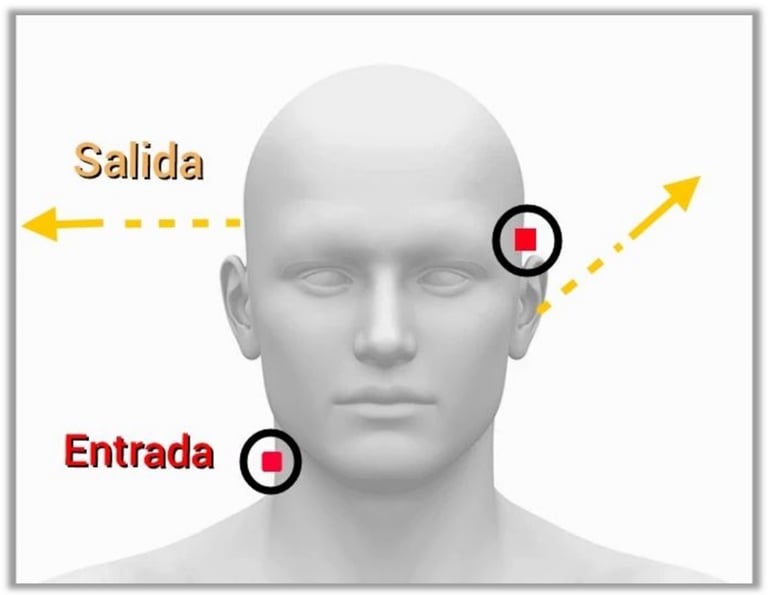

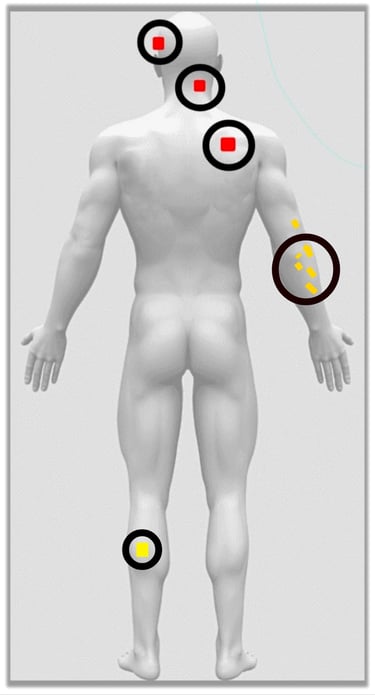

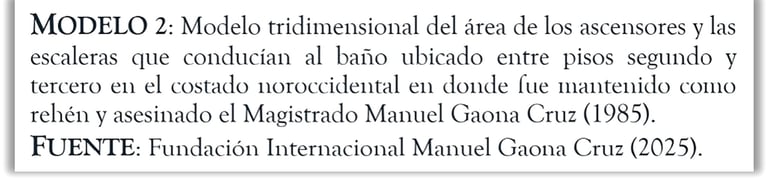

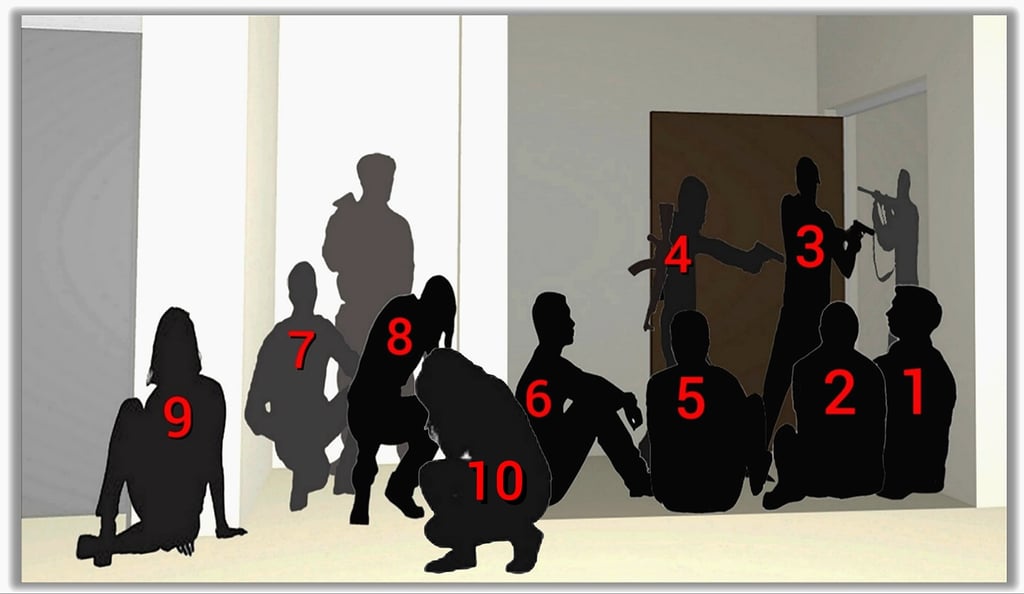

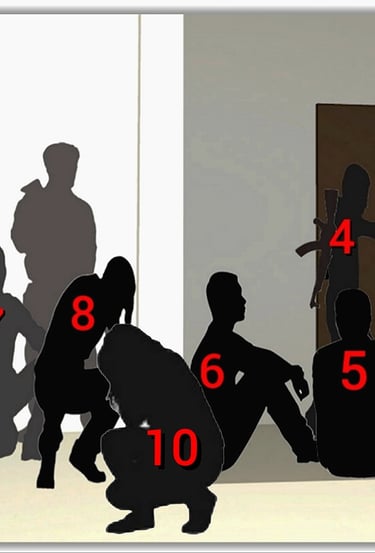

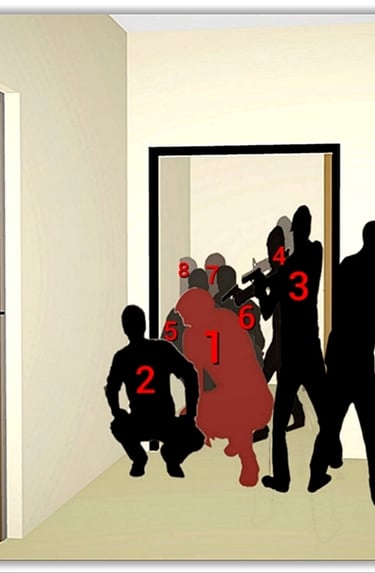

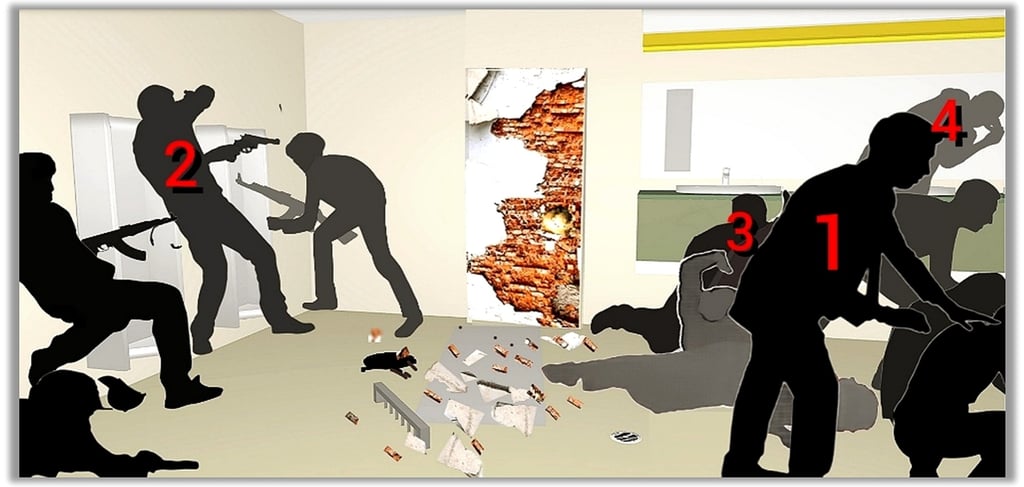

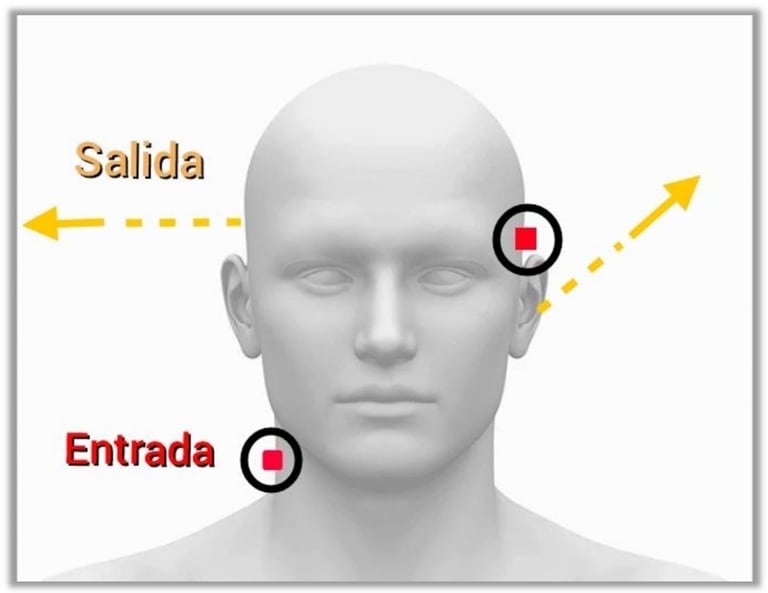

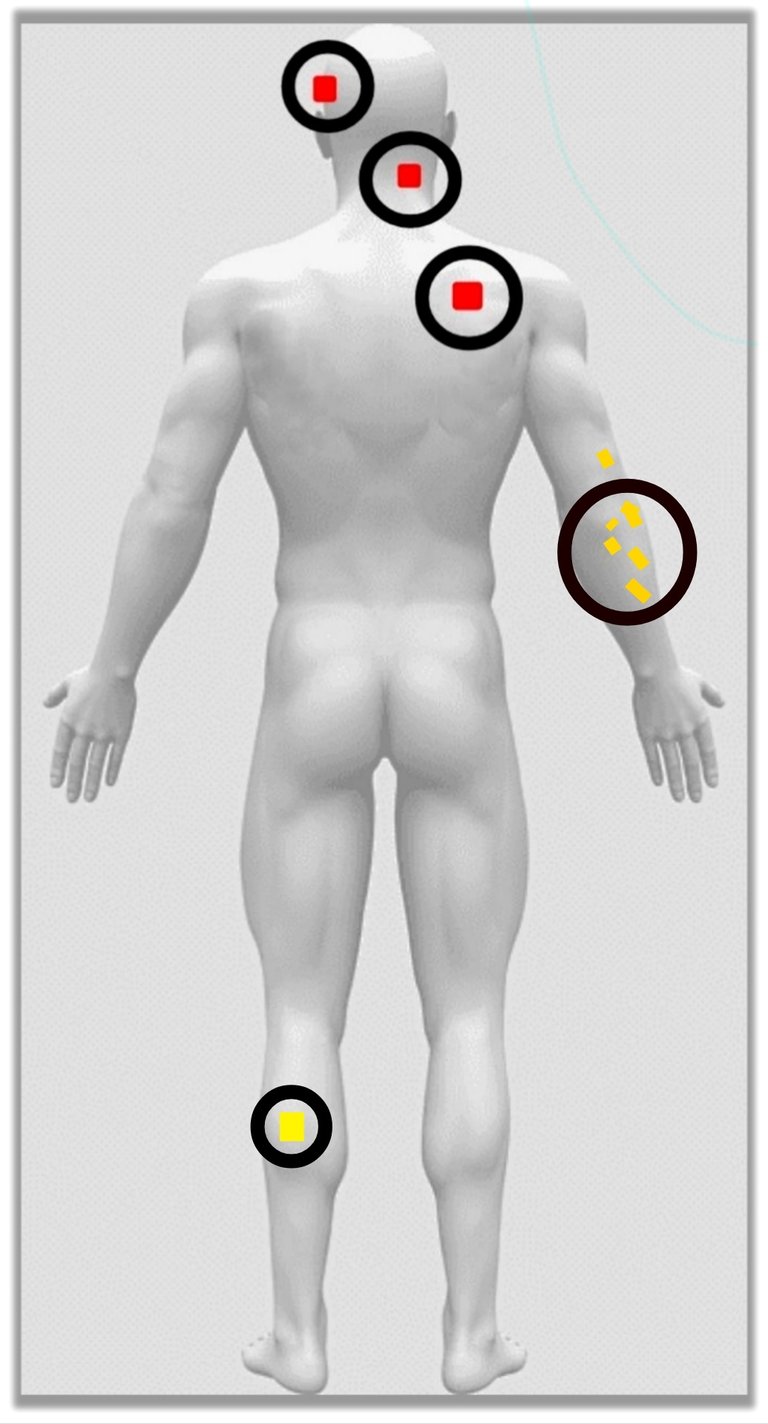

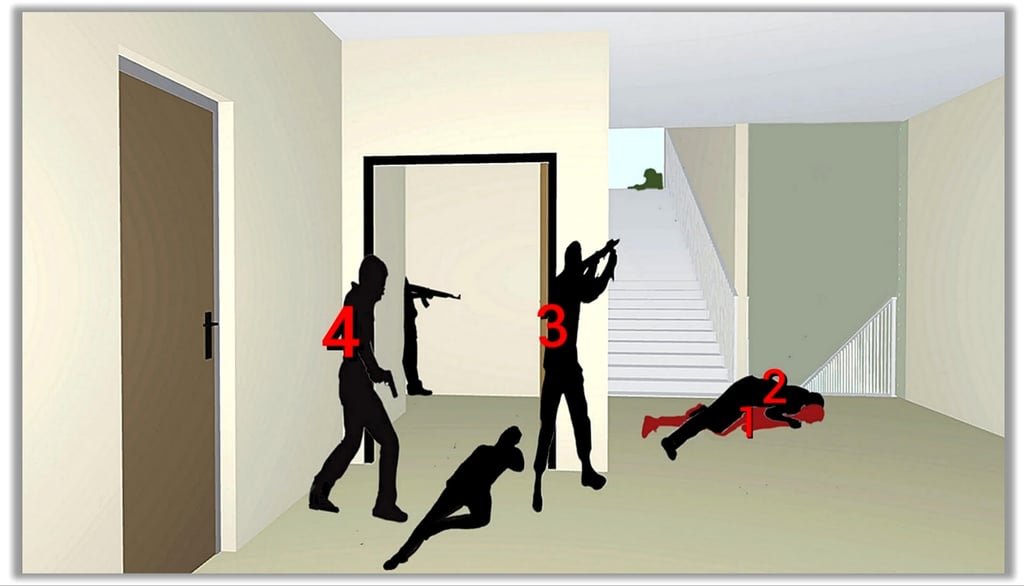

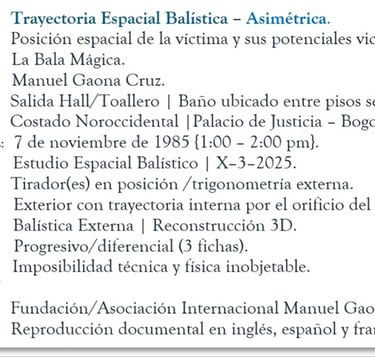

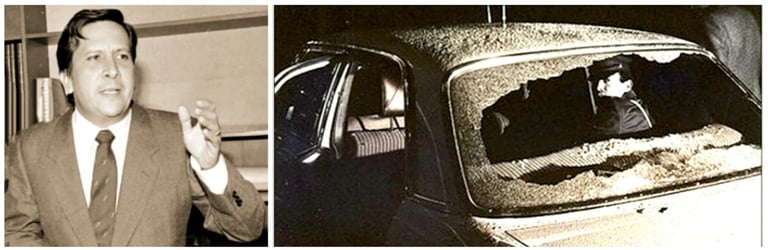

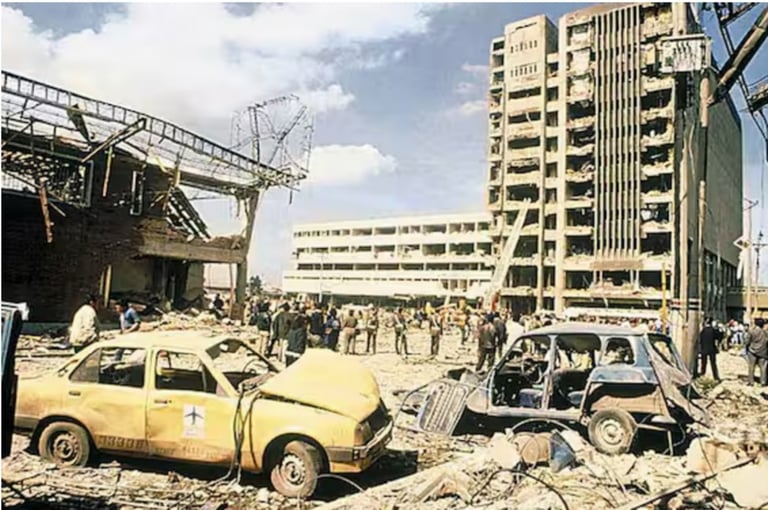

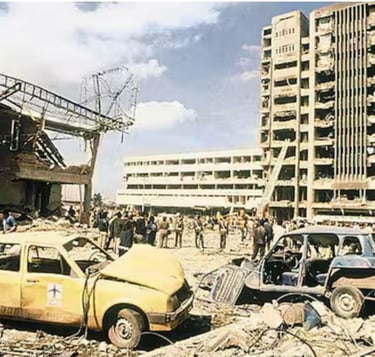

Justice Gaona was taken hostage by the M-19 guerrillas upon hearing the guerilleros calling his name and looking form him everywhere and, more particularly, after the Justices of the Constitucionalista Chamber were forced to interrupt their session and hide in nearby offices, right after Justice Gaona was, in fact, delivering the opinion of the Court on the constitutionality of the Extradition Treaty between Colombia and the United States (see MGC Death - The Kidnapping of Justice Manuel Gaona Cruz). Manuel Gaona Cruz was the first hostage that the guerrilleros sought upon entering the Court. He was assassinated by the M-19 guerrillas during the seizure of the Palace of Justice in Colombia on Thursday, November 7, 1985, after refusing to enter the crossfire and serving as a human shield for the guerrillas who were aiming at his head and back (see MGC Death - Forensic Reconstruction of the Crime Scene). More than half a dozen witnesses who were with the Justice (holding hands, behind, beside, beneath) witnessed his execution at the hands of the guerrillas and described, under oath and before the Colombian authorities who investigated his crime, the details of his kidnapping, murder, last words, and fatal wounds (see MGC Death - Testimonial Evidence; see also the Supreme Court's Truth Commission Final Report, Id., Informe Final: Comisión de la Verdad, pages 164-166).

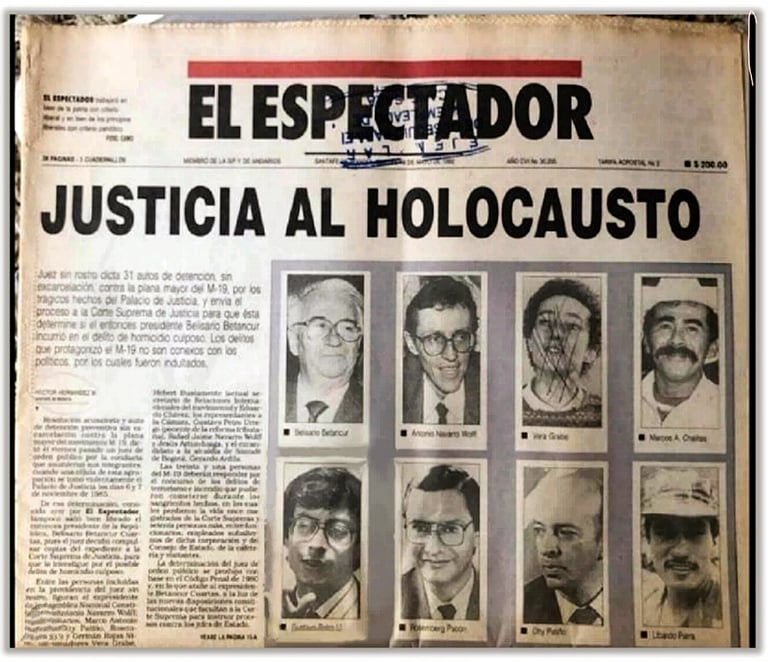

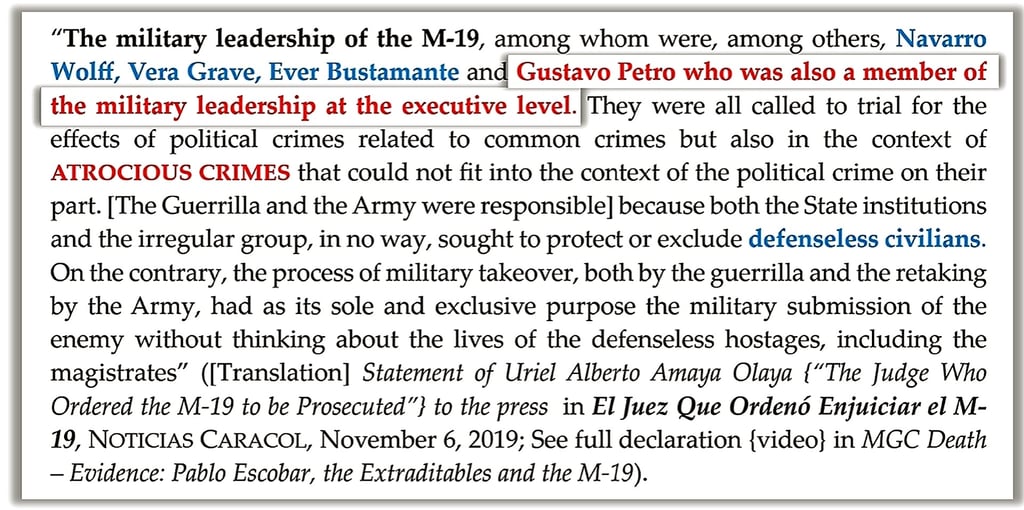

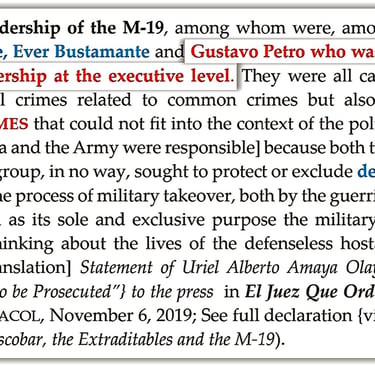

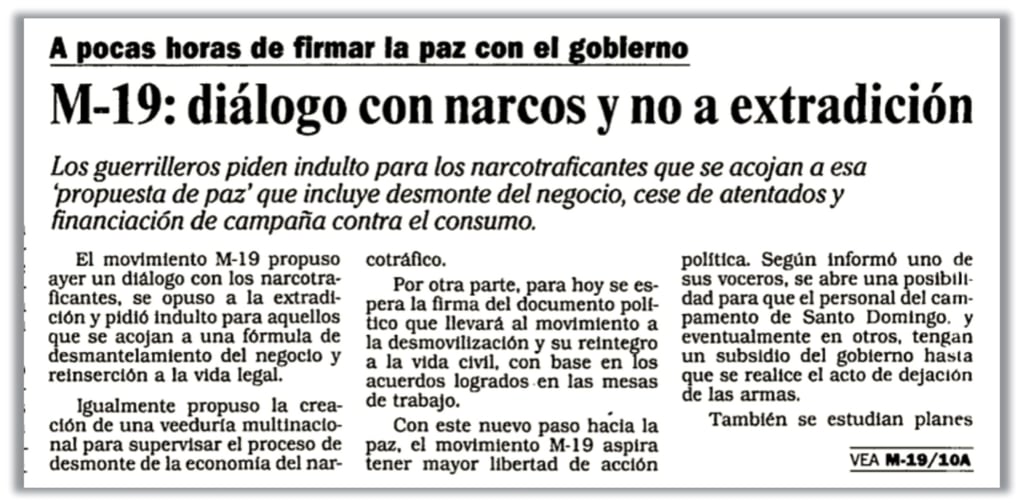

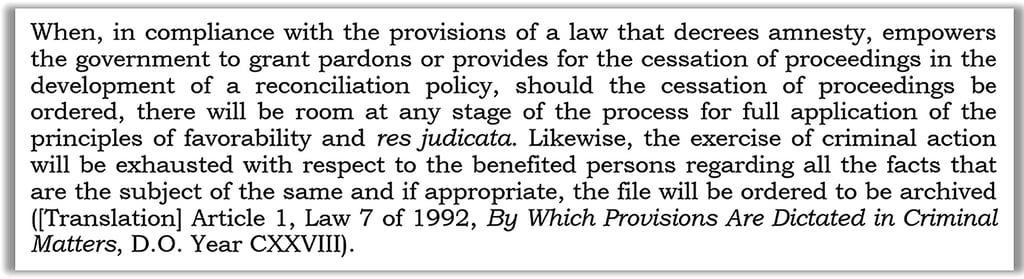

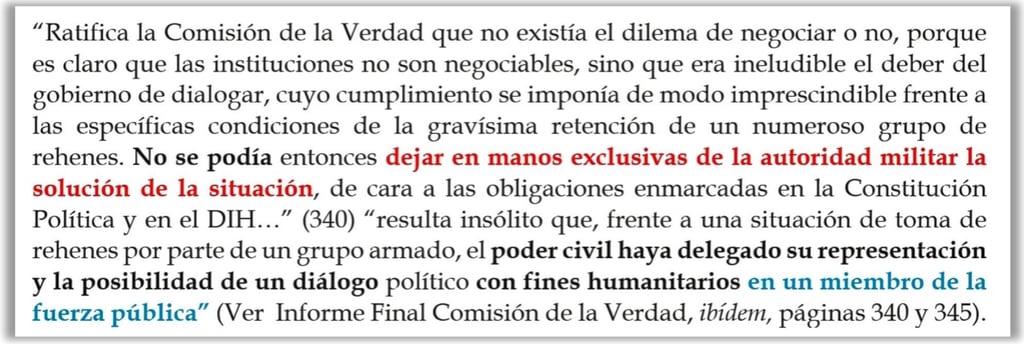

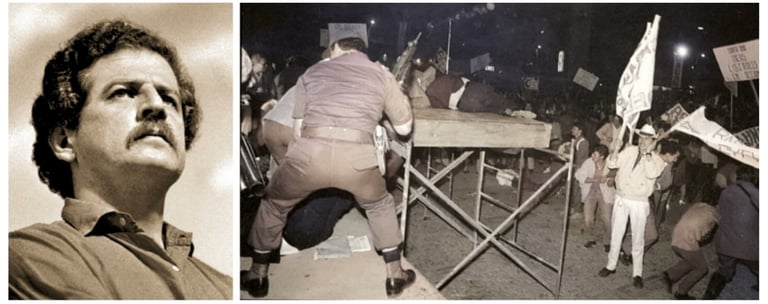

In 1989, the Congress of the Republic of Colombia approved a pardon law in favor of the M-19 guerrilla group (Law 77 of 1989). Despite the efforts of the government at the time to guarantee the impunity of the M-19 for the crimes committed in the Palace of Justice in order to facilitating the demobilization of the terrorist group, in January 31st of that year, the 30th Criminal Investigation Judge of Bogota, Uriel Alberto Amaya Olaya, filed charges against the military leadership of the M-19 for the crimes of rebellion, homicide, kidnapping and falsification of public documents as well as for human rights violations and the atrocious crimes committed by the guerrillas that, according to the Judge, were not covered by the political crime of rebellion (see Declaration of Judge Amaya in “El Juez Que Ordenó Enjuiciar al M-19” [The Judge Who Ordered the Prosecution of the M-19], NOTICIAS CARACOL, November 2019). The Judge also requested the Supreme Court of Justice to open an investigation against former President Belisario Betancur Cuartas, given the power vacuum that existed during the seizure and recapture of the Palace of Justice, and against Defense Minister Miguel Vega Uribe for human rights violations committed by the military forces that participated in the recapture.

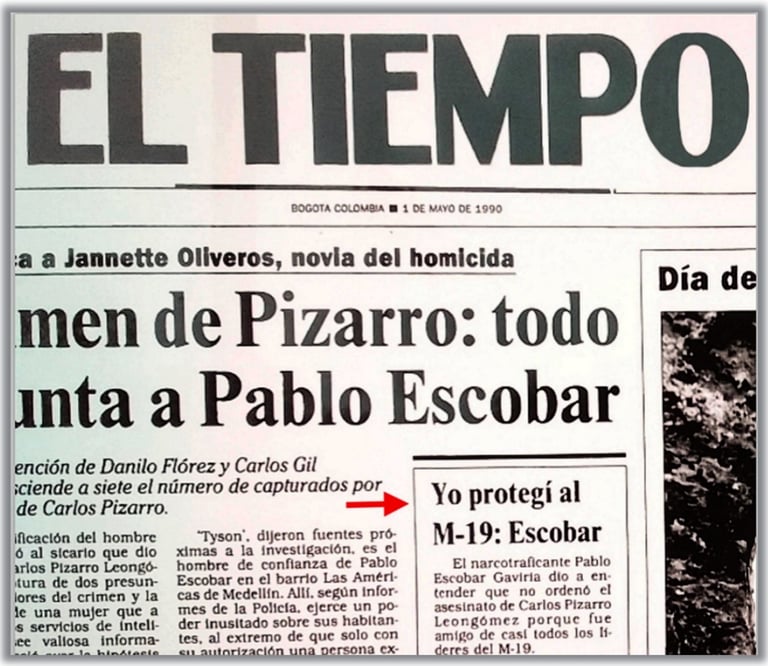

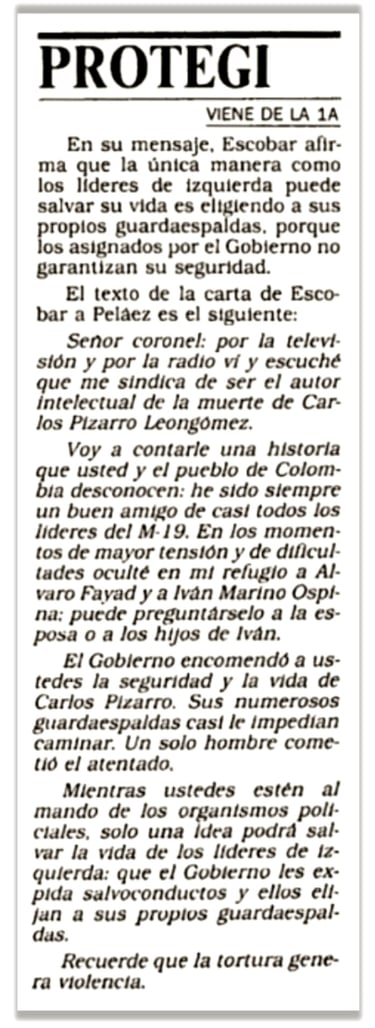

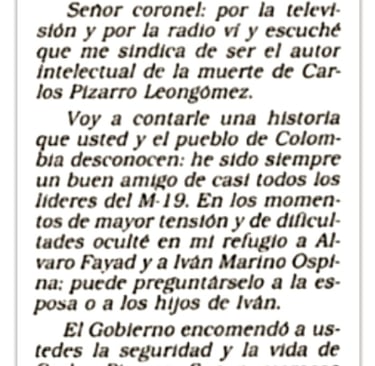

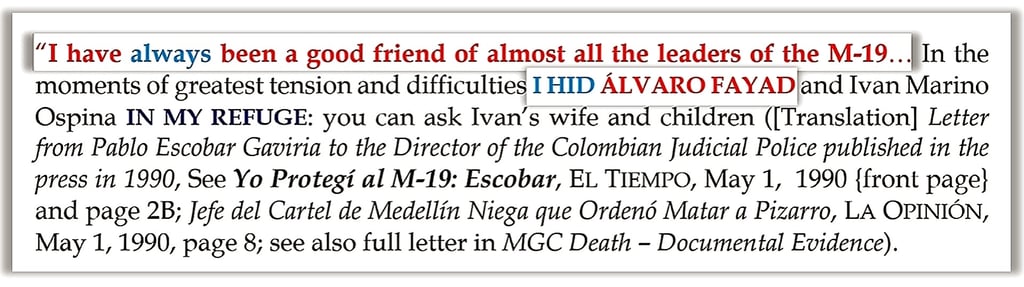

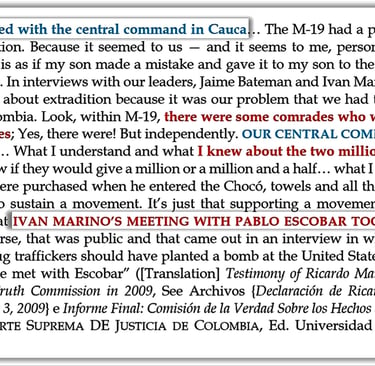

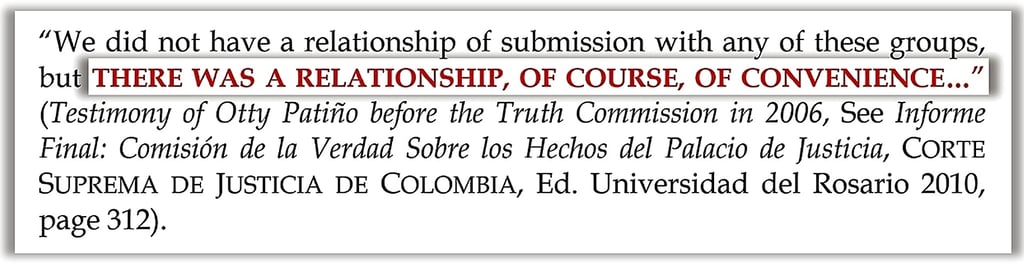

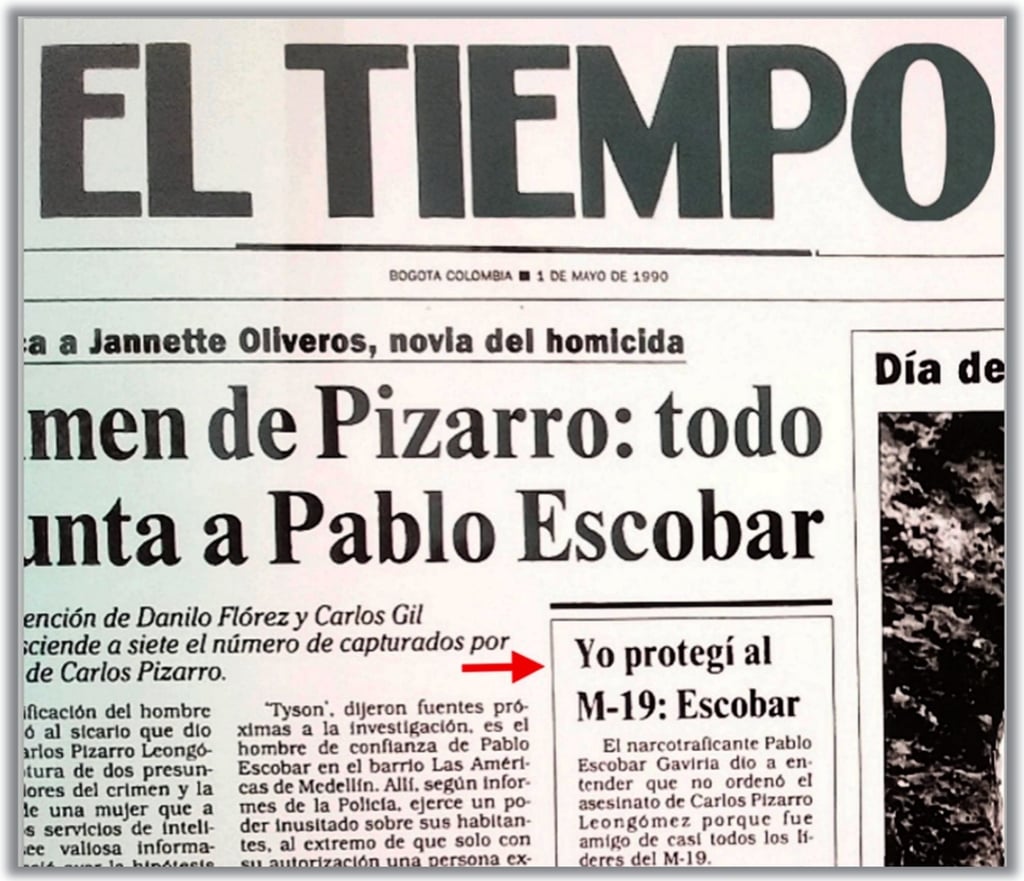

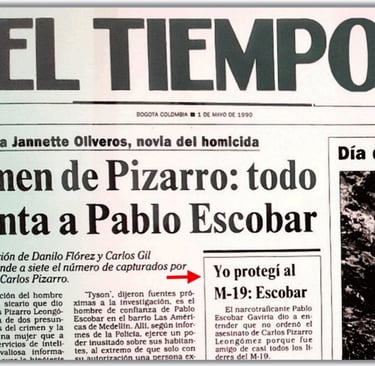

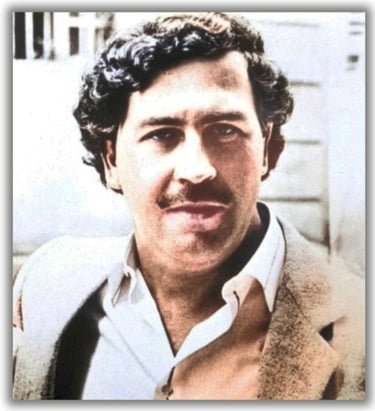

In 1990, in a letter signed and fingerprinted by Pablo Escobar, and addressed to the Commander of the National Directorate of Judicial and Investigative Police of Colombia (DIJIN), Colonel Oscar Peláez Carmona, Escobar acknowledged his relationship with the M-19 leaders, which he described as very close, stating that: "I have always been a good friend of almost all the M-19 leaders... In times of greatest tension and difficulty, I hid Álvaro Fayad and Iván Marino Ospina in my refuge" (Statement by Pablo Escobar Gaviria in 1990, see Letter from Pablo Escobar to the media and to the Commander of the Judicial and Investigative Police Directorate (DIJIN) in "Yo Protegi al M-19: Escobar" [I Protected the M-19: Escobar], EL TIEMPO, May 1, 1990, pages 1A and 1B; see also “El Jefe del Cartel de Medellin Niega Haber Ordenado Matar a Pizarro" [Medellin Cartel Chief Denies Ordering Pizarro's Killing,"LA OPINIÓN, May 1, 1990, page 8 {full letter in MGC Death – Documentary Evidence}). In an interview with Noticias Caracol, former M-19 commander and (current) Colombian president Gustavo Petro Urrego stated: "Álvaro Fayad was the one who planned the takeover of the Palace of Justice" (see Interview {video} in MGC Death - Documentary Evidence - Pablo Escobar and the M-19).

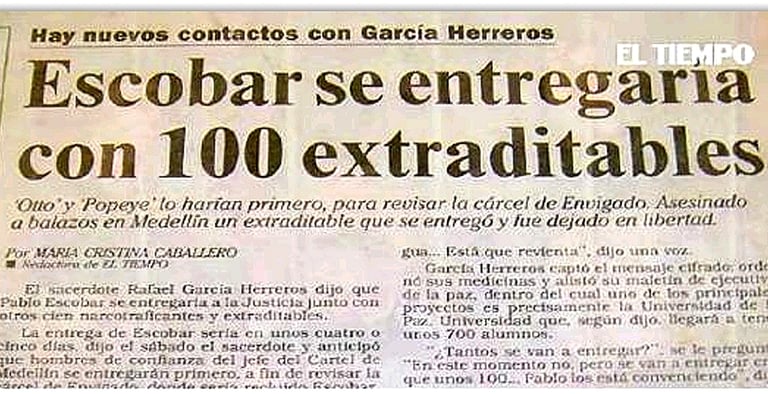

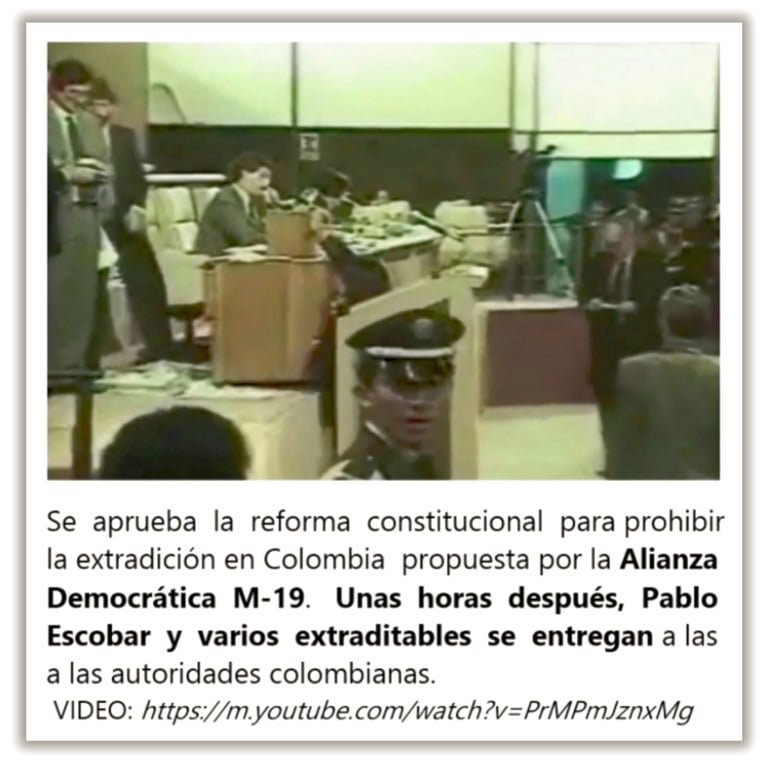

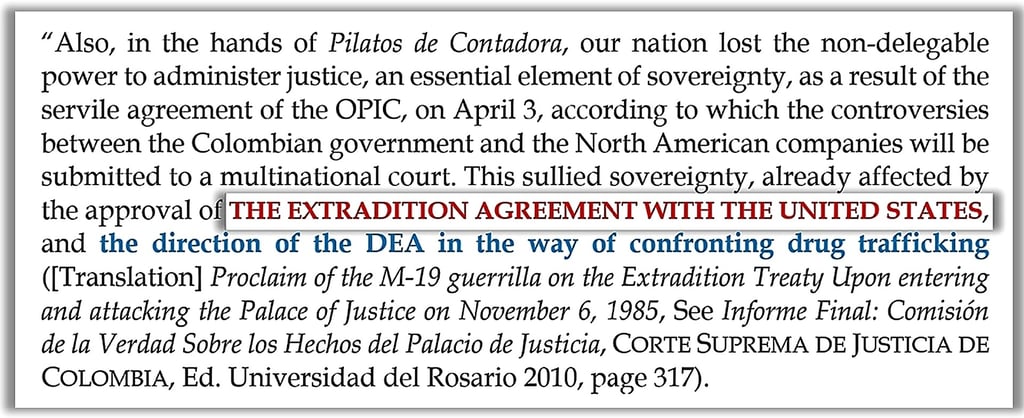

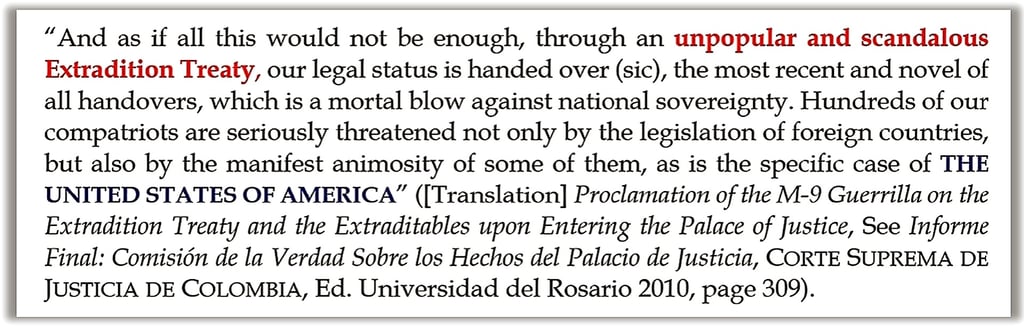

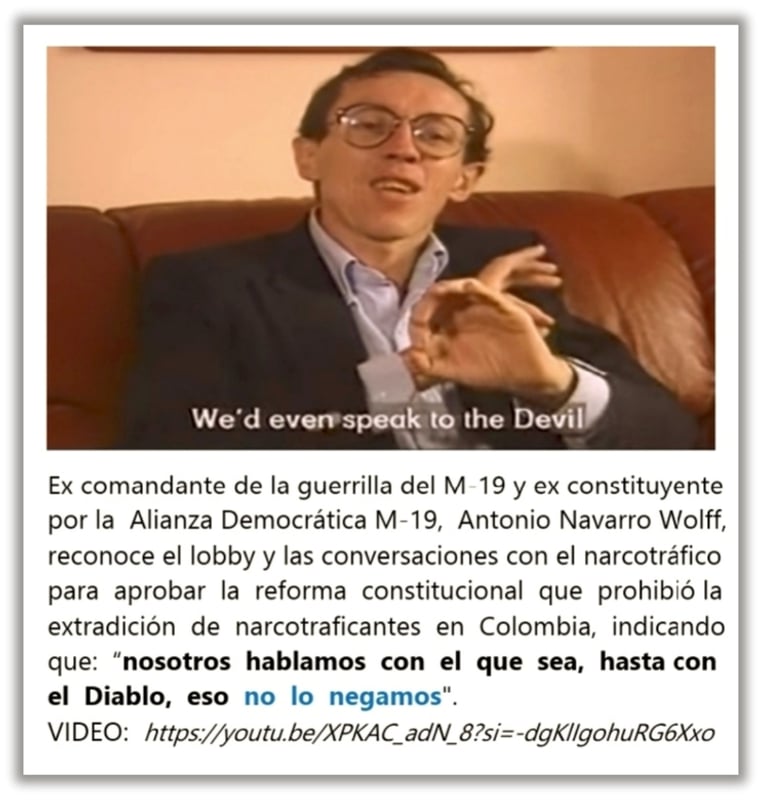

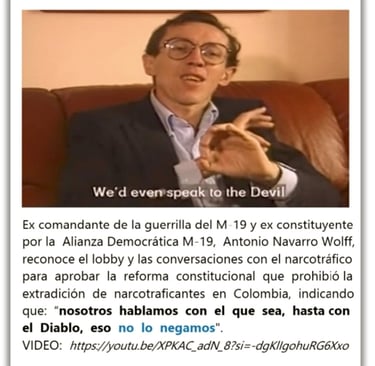

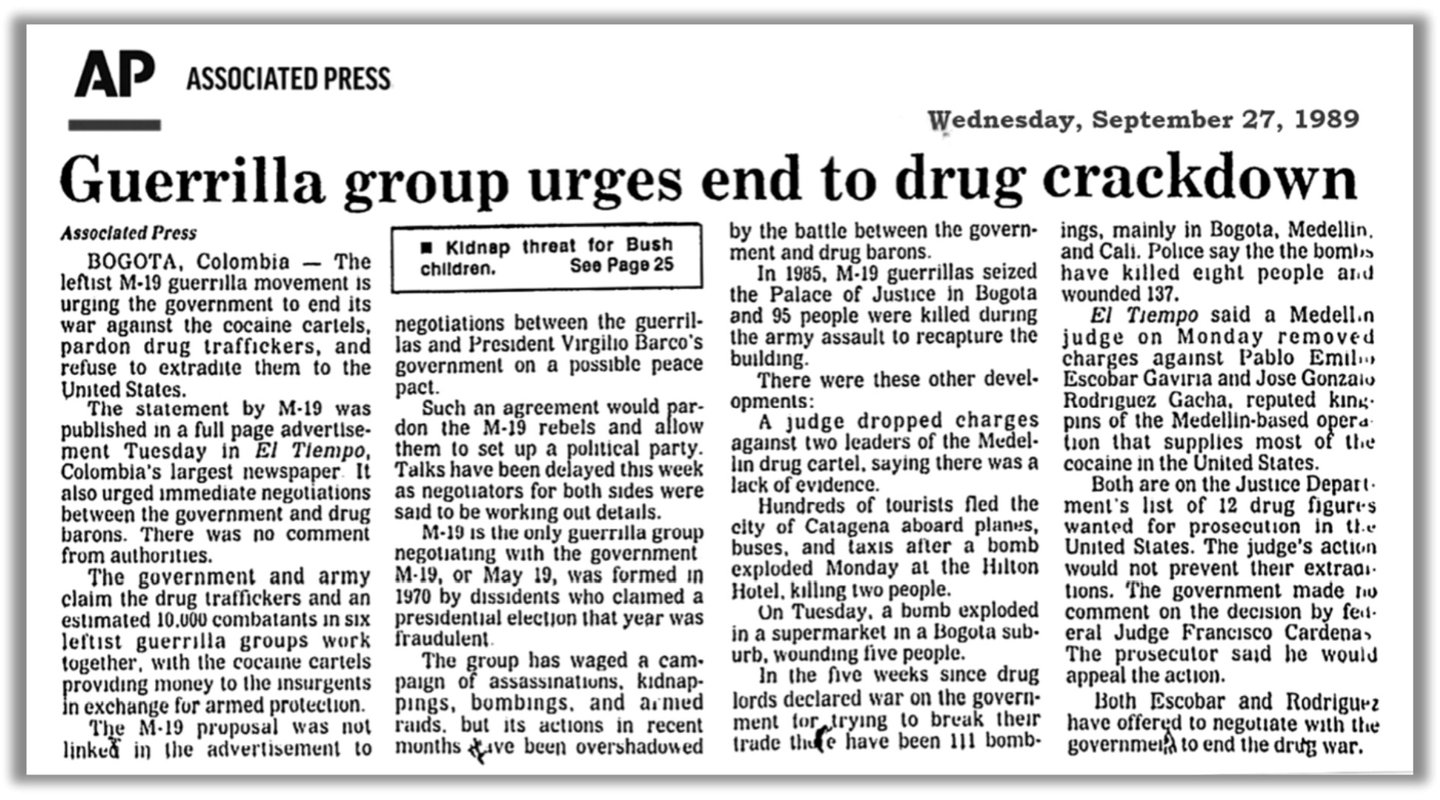

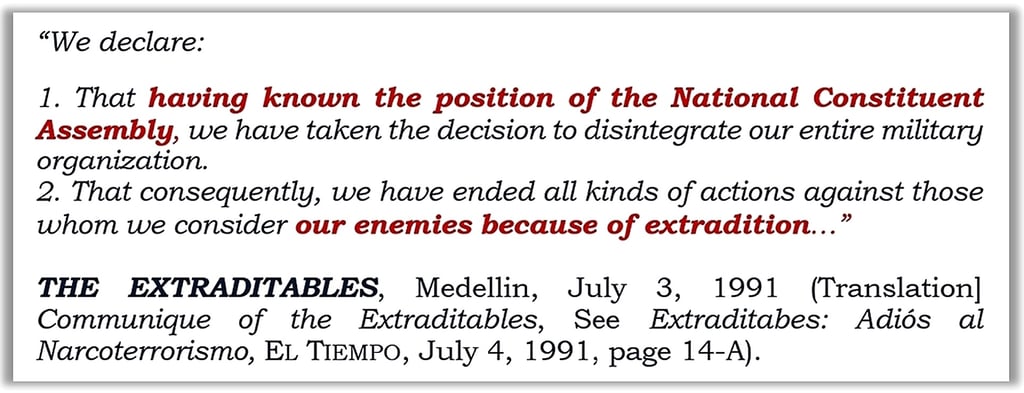

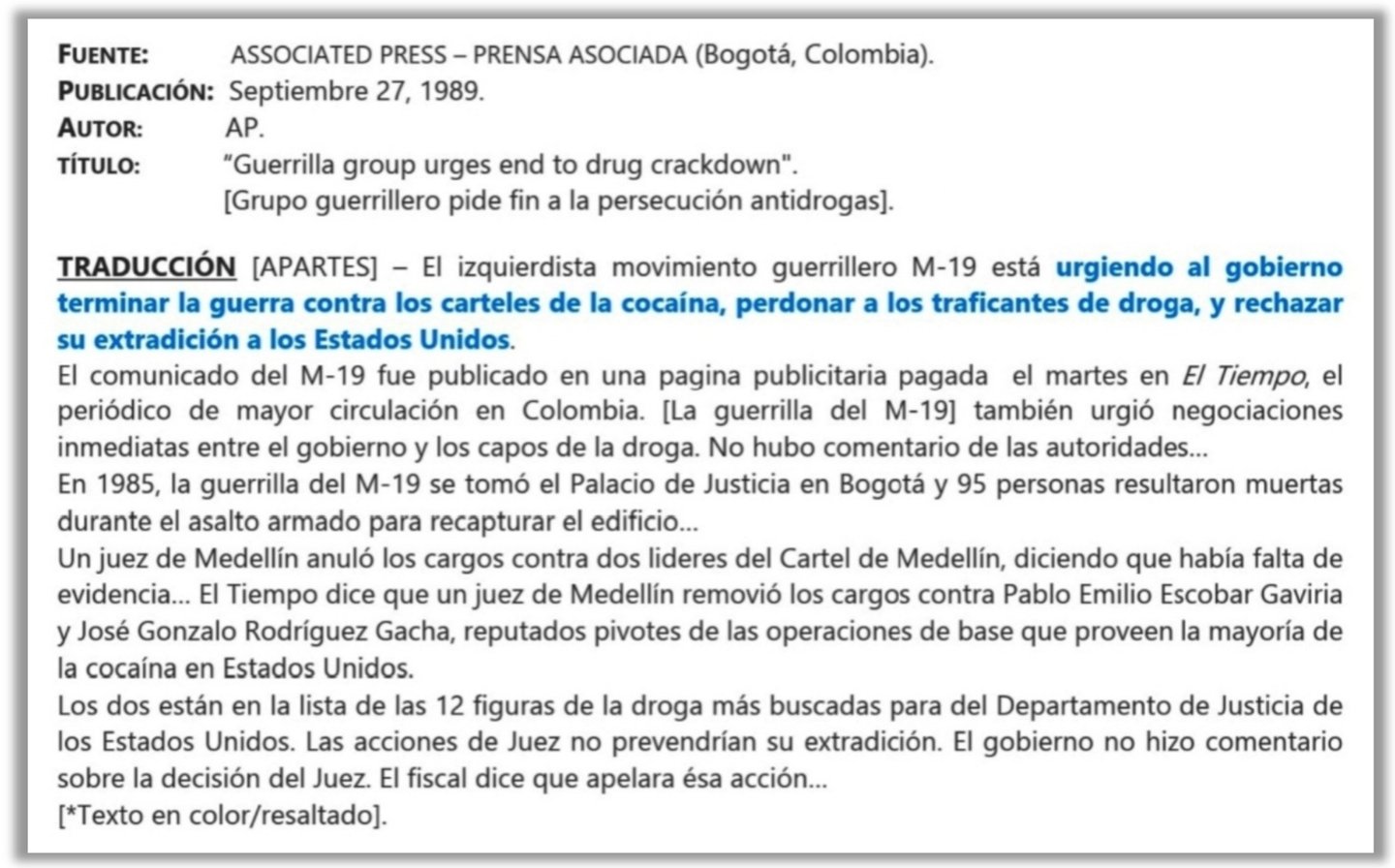

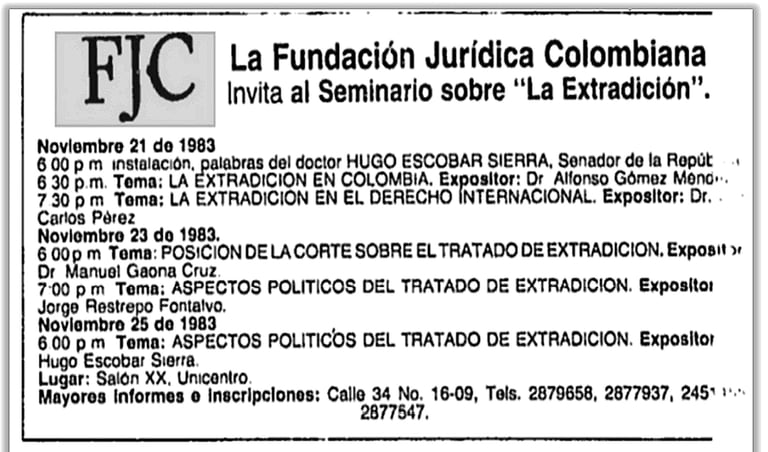

In 1991, the Democratic Alliance M-19 party, through its leader and former M-19 commander, Antonio Navarro Wolff, introduced a constitutional amendment proposal to prohibit the extradition of Colombian drug traffickers. With 45 votes in favor and 5 against, the M-19 successfully obtained a ban on extradition in Colombia. Pablo Escobar surrendered to Colombian authorities along with 100 other Extraditables on the same day the constitutional reform was passed. His surrender was subject to two conditions: first, that the recently passed constitutional reform be guaranteed, and second, that his trusted men be able to build the prison for him and the Extraditables, which he called "the Cathedral." In an interview with the international press, former constituent and former M-19 commander Navarro Wolff acknowledged the drug trafficking lobbying that helped pass the reform and stated: "We talk to anyone, I won't deny that" (see interview in MGC Death - Documentary Evidence).

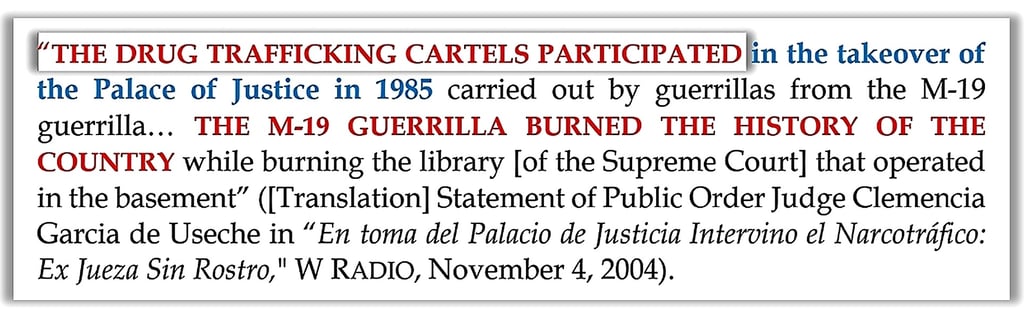

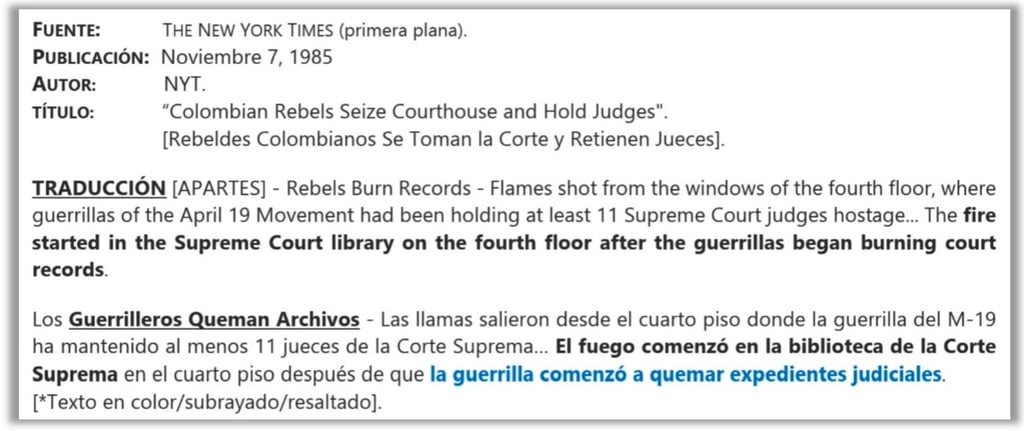

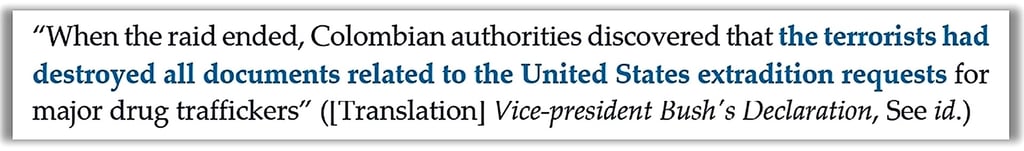

In 1992, Public Order Judge Clemencia García de Useche issued an arrest warrant without the benefit of release for the crimes of terrorism, rioting, and arson against the M-19 military leadership, including former M-19 commander and current president of Colombia Gustavo Francisco Petro Urrego and former M-19 commander Antonio Navarro Wolff. In her ruling, the Judge established a criminal conspiracy between drug traffickers and the M-19 guerrillas to attack the Palace of Justice, and formally accused the M-19 of committing acts of terrorism and rioting after burning the extradition files against drug cartels housed in the Palace of Justice's library. Incidentally, the front page of The New York Times, published on November 6, 1985, reads: "Rebels Burn Records." Shortly thereafter, the Colombian Congress approved a reform to the pardon law (Law 7 of 1992) extending the pardon to all crimes committed by this guerrilla group; thus, guaranteeing impunity for the atrocities committed by the terrorist group during the 1985 takeover of the Palace of Justice.

Giraldo Mesa, La Sencillez de la Genialidad [The Simplicity of Genius], AMBITO JURIDICO LEGIS, No. 189, 2005). His works on Latin American presidentialism and constitutional control, his fight against drug trafficking, and his most cited opinions remain in the memory of the thousands of students he educated and in the annals of the courts and institutions that nowadays preserve his legacy. The family, the Foundation, and the Manuel Gaona Cruz International Association are especially grateful for the contributions of the Government of the Republic of France, the Sorbonne University of Paris 1, Harvard University, the University of Los Andes, the University of Rosario, the University of Boyacá, the Francisco Jose de Caldas District University of Bogota, and the Supreme Court of Colombia, as well as for the acknowledgments of former Presidents of the Sorbonne University, François Luchair and Pierre-Yves Hénin. We extend our most sincere gratitude to the Judges and Justices of the Supreme Court of Colombia who, over the years, helped dispel rumors vis-a-vis the events that shed light on the assassination of the professor and Supreme Court Justice, Manuel Gaona Cruz. Our thanks also go to the researchers, journalists, experts, professors and academics, and to all those who helped us in Colombia, the United States, and France. We would like to extend our special thanks to Carmel Media Lab in the United States, as well as to Manuel Gaona Cruz's friends and students from all universities for sharing their messages, stories, and heartfelt recollections (see Investigation - Special Thanks).

In 2001, following public pressure from dozens of family members seeking to know the fate of their loved ones who disappeared during the takeover of the Palace of Justice, the Attorney General's Office opened a formal investigation to determine the criminal responsibility of the military personnel who participated in the retaking of the Palace of Justice.

In 2005, the Colombian Supreme Court instituted a Truth Commission composed of three former Chief Justices to investigate and establish the truth on what happened at the Palace of Justice considering all parties involved, that is: the government of former President Belisario Betancourt Cuartas, the Army, the M-19 guerrillas, and the Medellin drug Cartel.

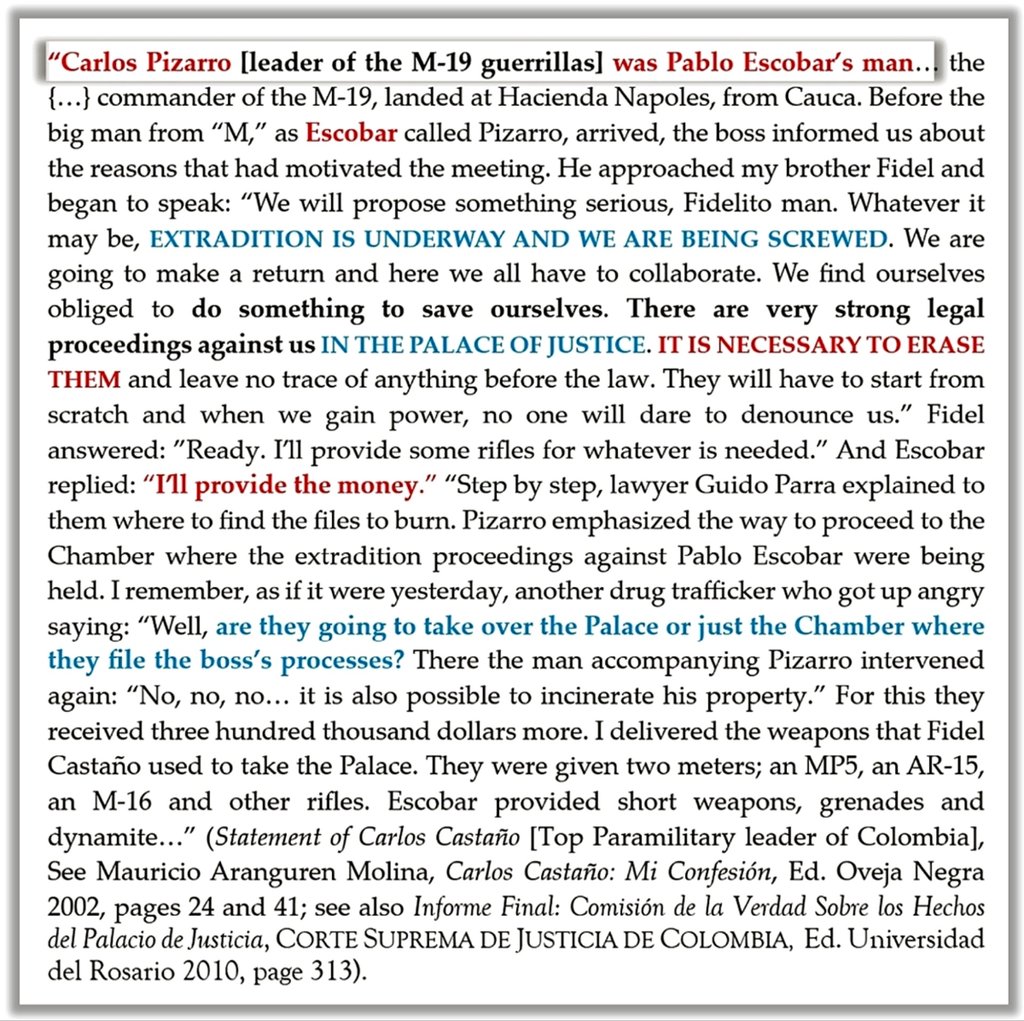

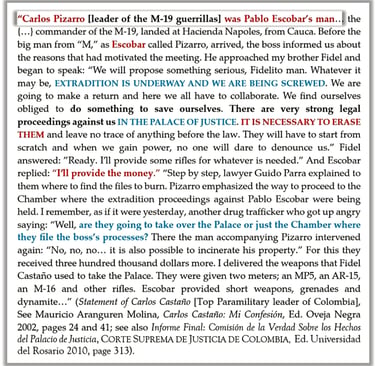

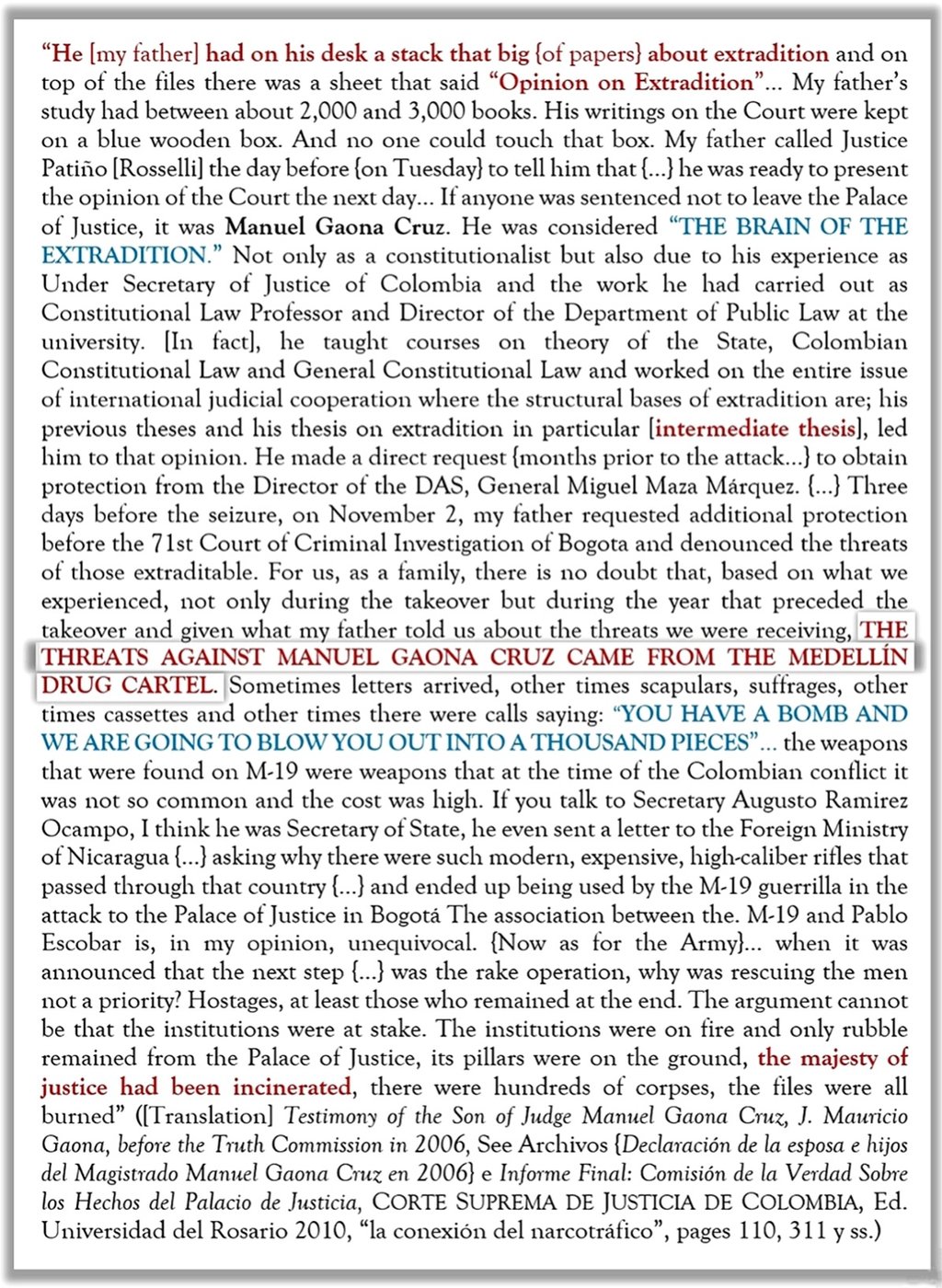

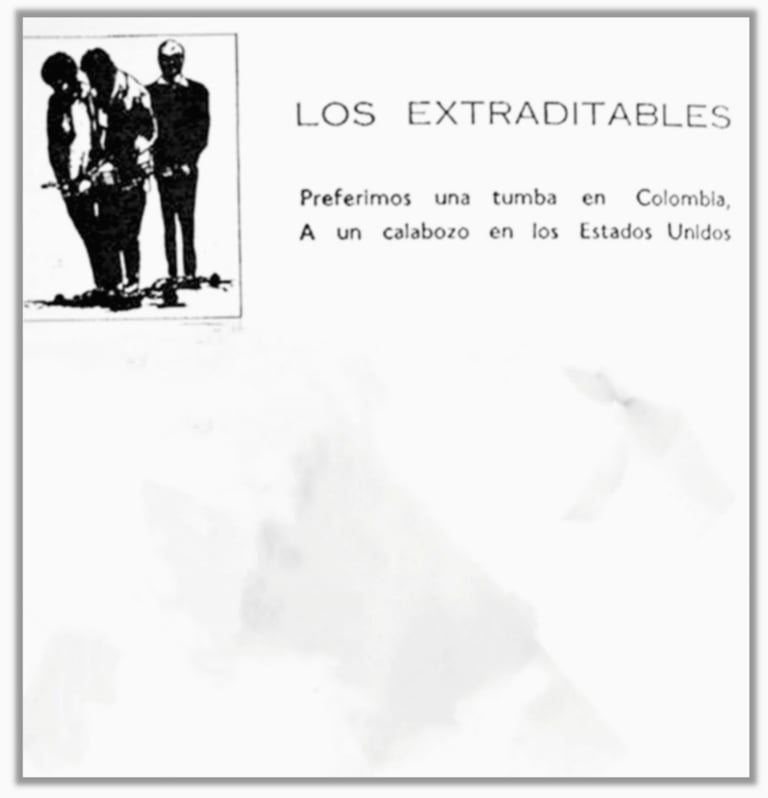

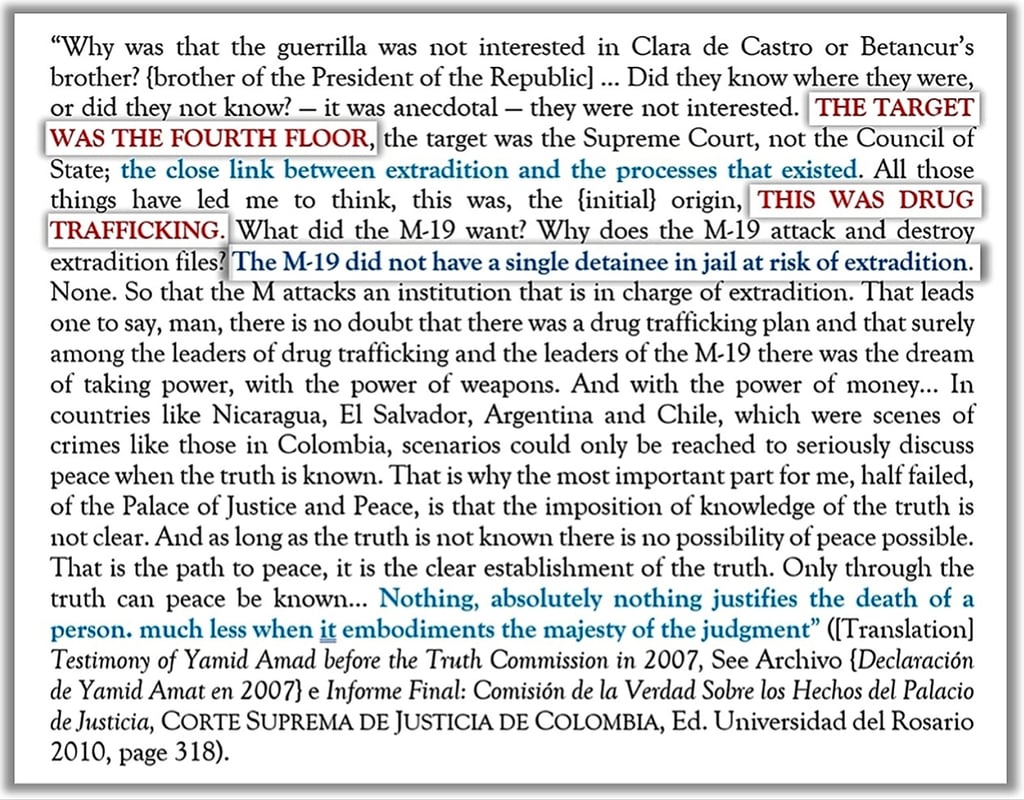

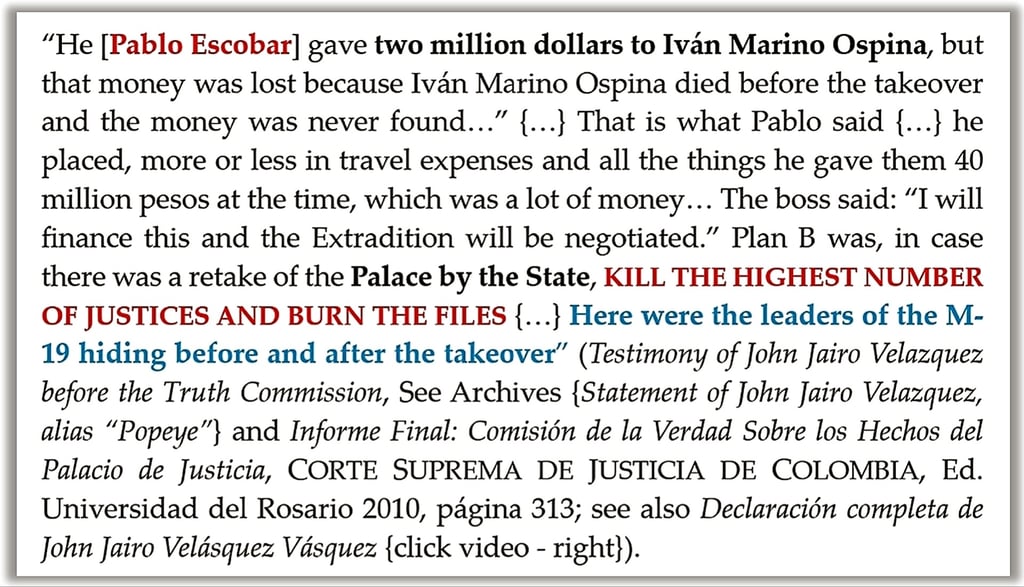

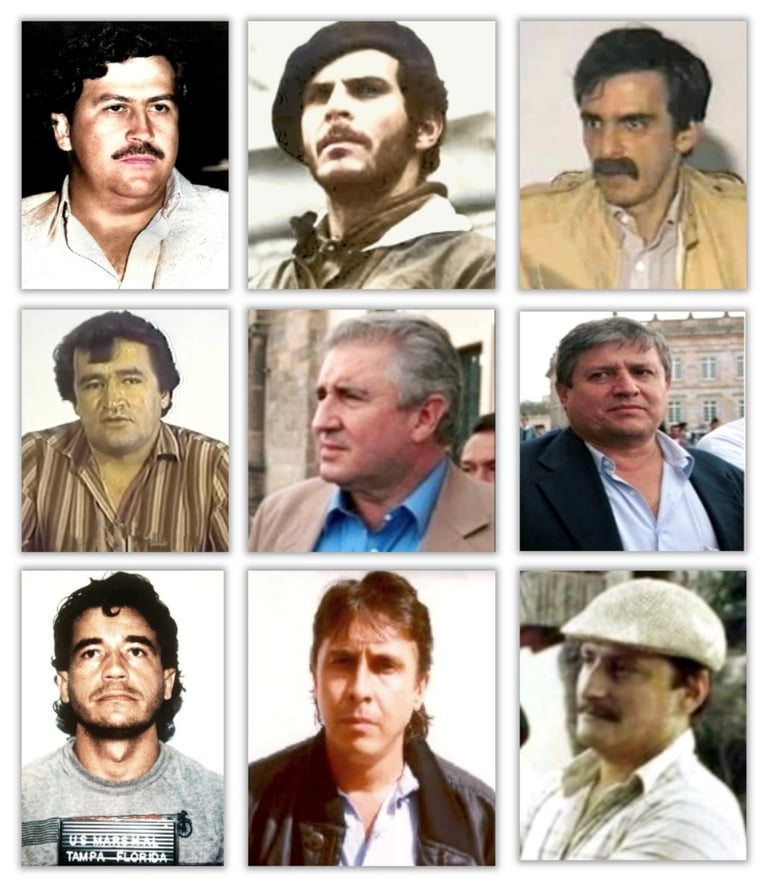

In June 1985 and following landmark decisions of the Constitutional Chamber of the Supreme Court on the Extradition Treaty, Pablo Escobar, the members of the Medellín Cartel, M-19 guerrilla commander Carlos Pizarro, lawyer Guido Parra Montoya, and the brothers Fidel and Carlos Castaño met at the Hacienda Nápoles near the city of Medellin to discuss how to halt extradition proceedings before the Constitutional Chamber. At the meeting, it was agreed to attack the Palace of Justice, burn the extradition files, and assassinate all the Justices of the Constitutional Court. In Escobar's words: "We are obligated to do something to save ourselves. There are very serious legal proceedings against us in the Palace of Justice. We must erase them and leave no trace before the law. They will have to start from scratch, and once we gain power, no one will dare to denounce us" (Statement by Carlos Castaño on Pablo Escobar and the meeting with the M-19 in Mauricio Aranguren Molina, Mi Confesión: Carlos Castaño Revela Sus Secretos, Ed. Oveja Negra 2002, pages 24 and 41). At the meeting, Pablo Escobar andthe Castaño brothers agreed on providing both the financing of the takeover and the provision of weapons, including handguns (see Testimony of Pablo Escobar's lieutenant John Jairo Velazques before the Supreme Court's Truth Commission in Informe Final: Comisión de la Verdad Sobre los Hechos del Palacio de Justicia, CORTE SUPREMA DE JUSTICIA DE COLOMBIA, Ed. Universidad del Rosario 2010, page 313; see also Escobar's full statement and letters in MGC Death - Documentary Evidence). Attorney Nule provided the M-19 guerrillas specific details regarding the location of the files against the Cartel as well as the exact location of the Constitutional Court deliberation room. Escobar gave the guerrillas precise instructions on what to do in the event of a recapture of the Palace of Justice by the army: "kill as many judges as possible and burn the files" (id., My Confession, page 41; Testimony of John Jairo Velazques).

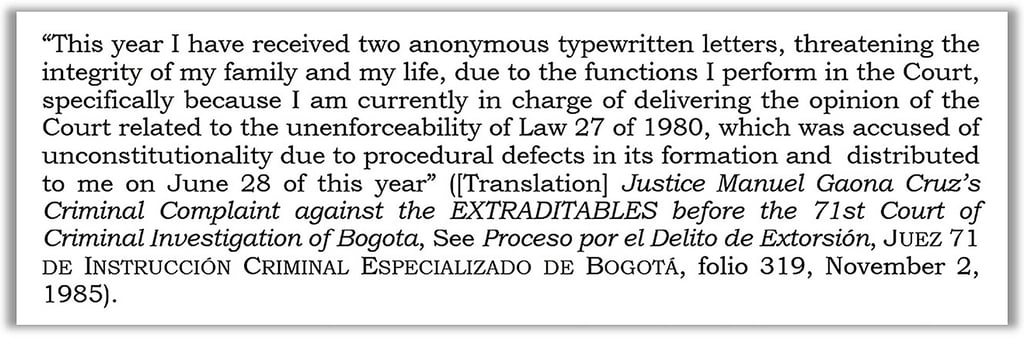

On November 2, 1985, Justice Manuel Gaona Cruz filed a criminal complaint before the 71st Criminal Investigation Court of Bogota, asking the judge to investigate the threats against him issued by "los Extraditables" (see Manuel Gaona Cruz's Criminal Complaint against Los Extraditables in MGC Death – Documentary Evidence). On Sunday, November 3, the last envelope from Pablo Escobar and "los Extraditables" arrived at Justice Gaona's home. Inside the envelope was a blank sheet of paper and a ballot. It was a long holiday weekend in Colombia and Manuel Gaona Cruz dedicated himself, almost nonstop, to writing his opinion on the law approving the Extradition Treaty. That Sunday, however, the justice paused to explain his decision and what was about to happen to his sons and wife. The premonition of his final hours was palpable. Defying the instructions of his bodyguards, the justice asked to be taken for a few minutes to the house where he grew up and met his wife Marina, to the Camilo Torres school where he studied, and to the gardens of the Universidad Externado where he had taught. The best lessons they received from their father, his sons recall, occurred when they went for walks, something the family could no longer do. Upon returning, the justice met with his children and wife in his home study. He hugged his wife and his 10-month-old baby, and told his 11 and 13-year-old sons that he would likely not see them grow up. "They want to prevent me from doing what I have to do. They want to force me to make a decision that goes against my principles, and I will never do that. Under no circumstances," he said. When his sons asked who Pablo Escobar was and why was he threatening them so much, the justice told them in a few words that Escobar was a criminal who wanted to take over the country. Justice Gaona told his sons that he hoped they would understand one day. "If something happens to me, I want you to know that I will miss you very much," he replied. All of them embraced in silence. Manuel Gaona Cruz asked his older children that when his daughter grew up, they would take her to Paris to walk on the bridges of the Seine River, visit her favorite bookstores, and read his thesis at the Sorbonne as he would have liked to do. He asked his wife Marina to travel with their children to France the next day and stay at their friends Simon and Noé's house. Marina refused, telling him: "We'll all leave after you present your report and sign the sentence. We'll wait for you, we'll all leave. We won't be separated. We'll always be together." On Tuesday, November 5, Manuel returned home early to fine-tune the details of his report. That night, he told his wife Marina, "I have a terrible feeling something bad is going to happen tomorrow. Call me at 11:30 AM. Tell Lyda [his secretary] to pass the call on to me even if I'm in court. I need to know you're okay." His typewriter clicked until dawn. On Wednesday, November 6, after saying goodbye with a kiss on the forehead, his children and wife watched the judge depart for the Palace of Justice for the last time at 8:00 AM. Manuel Gaona Cruz was carrying the opinion of the Court under his arm.

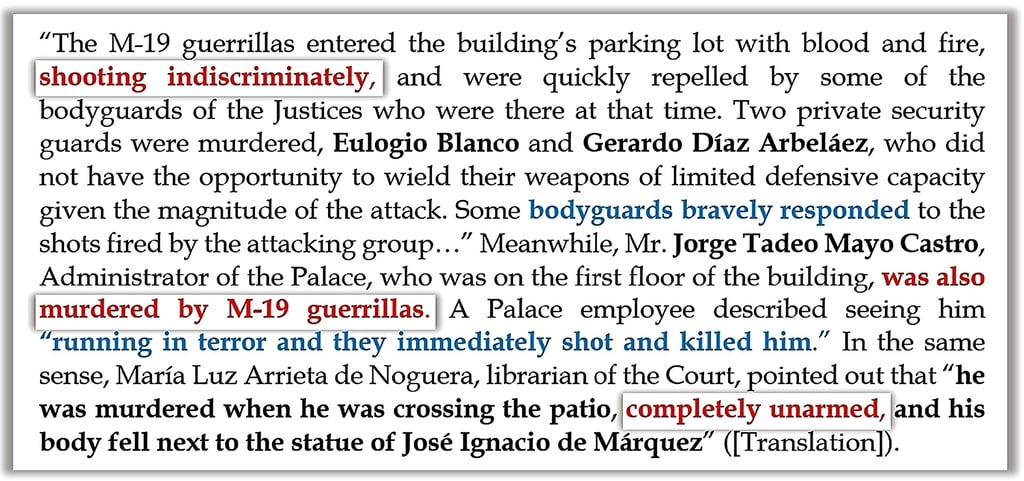

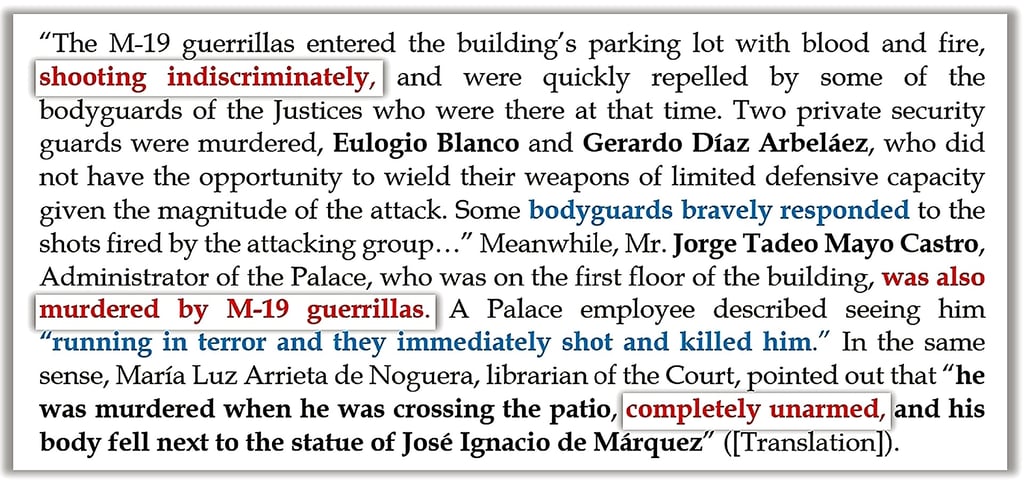

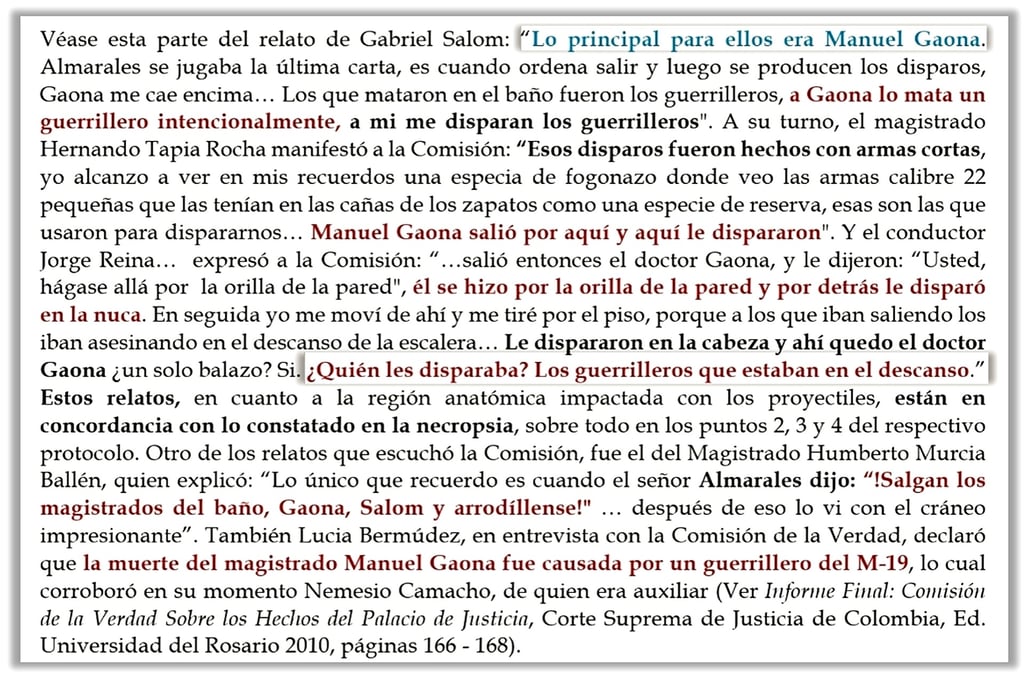

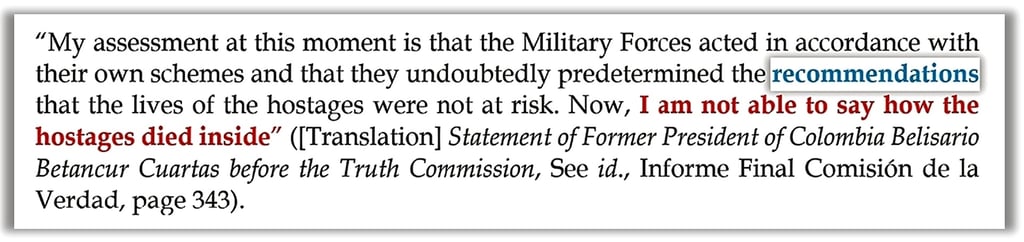

In 2010, the Truth Commission established by the Colombian Supreme Court of Justice concluded in its final report that Justice Manuel Gaona Cruz was murdered by the M-19 guerrillas, right after he refused to lead a group of hostages out of a bathroom and into the crossfire to be used as a human shield for the guerrillas who were pointing their guns at his head and back. The Commission’s final report, which has been also considered by the Inter-American Court of Human Rights (ICHR), concluded that the M-19 guerrillas committed crimes against humanity and flagrant violations of International Humanitarian Law (IHL) during the takeover of the Colombian Palace of Justice, an inhumane armed action that —according to the Commission— cannot be justified as a political action. Among the crimes attributed to the M-19 guerrillas by the Truth Commission, yet not prosecuted (due to amnesty laws) are: kidnapping and hostage-taking, the use of human shields, cruel and inhuman treatment, violations of human dignity and liberty of hostages, and the homicide of Manuel Gaona Cruz (Justice of the Constitutional Chamber), Luz Stella Bernal Marin (Assistant Lawyer to the Council of State), Luis Humberto Garcia (Driver), Placido Barrera Rincon (Driver for Justice Manuel Gaona Cruz), Jorge Tadeo Mayo Castro (Administrator of the Palace of Justice), Eulogio Blanco (Security Guard), and Edgar Gerardo Diaz Arbelaez (Security Guard), in addition to other drivers and bodyguards who tried to resist the guerrillas’ entry through the Palace of Justice garage (see Truth Commission's Final Report in Comisión de la Verdad, pages 163 and 322-330). The Commission further concluded that the takeover of the Colombian Palace of Justice was financed by Pablo Escobar to destroy all files and records against the Medellín Cartel and to prevent the Constitutional Chamber of the Court from declaring the law approving the Extradition Treaty between Colombia and the United States as constitutional. The criminal relationship between drug trafficking and the M-19 guerrillas was extensively documented by the Commission in its final report (Id., pages 311-319). The Commission further concluded that Pablo Escobar, the Medellín Cartel, and the M-19 guerrillas acted in concert. Similarly, the Commission attributed an historical and institutional responsibility to the government of former president Belisario Betancur Cuartas for the existing constitutional power vacuum, press censorship, and the lack of interest in preserving the lives of the hostages (Id., pages 331-352). The Commission also established that the public forces in charge of the military operation during the recapture of the Palace of Justice committed crimes and violations against International Humanitarian Law (IHL) related to the violation of the international principle of Distinction between civilians and military targets, the excessive use of force, the Principle of Proportionality, Necessity and humanity, and the forced disappearance of several cafeteria employees and Palace officials, as well as the alteration of evidence (Id., pages 353-408).

In 2007, a meeting was held at the Attorney General's office between National Deputy Comptroller and Justice Manuel Gaona Cruz' son, J. Mauricio Gaona, Deputy Prosecutor Angela Maria Buitrago and the Attorney General of Colombia Mario Iguaran Arana, to clarify whether after six years of investigation, there was evidence of Justice Gaona's execution by the Army after leaving the Palace of Justice, or whether the credibility of the witnesses who saw his execution by the M-19 inside the palace of Justice had been impeached. The prosecutors' response was unmistakable: "no evidence showed Justice Gaona left the Palace alive, nor had any witness confirmed that, although the departure of other individuals was nonetheless established." Despite Mauricio Gaona's insistence that the M-19 should be investigated for crimes against humanity, the Prosecutor explained that her investigation was mainly focused on the Army's actions and the disappeared persons, noting further that a congressional pardon prevented a deeper investigation into the guerrillas. The following year, Prosecutor Buitrago charged former military officers, including Alfonso Plazas Vega and Jesus Armando Arias Cabrales, with the forced disappearance of 11 people who survived the siege, leading to prison sentences for the military. The convictions were reviewed by higher courts, with colonel (r) Alfonso Plazas Vega being acquitted in 2015, while general (r) Jesús Armando Arias Cabrales had his 25-year sentence confirmed in 2019. In 2023, the Supreme Court confirmed 40-year sentences against general (r) Edilberto Sanchez Rubiano and Captain Oscar William Vasquez Rodriguez, and in 2024, the Superior Court of Bogotá confirmed 31-year sentences for General (r) Iván Ramirez Quintero and Colonel (r) Fernando Blanco Gómez for the same crime.

Supreme Court of Justice of Colombia November 7, 1985

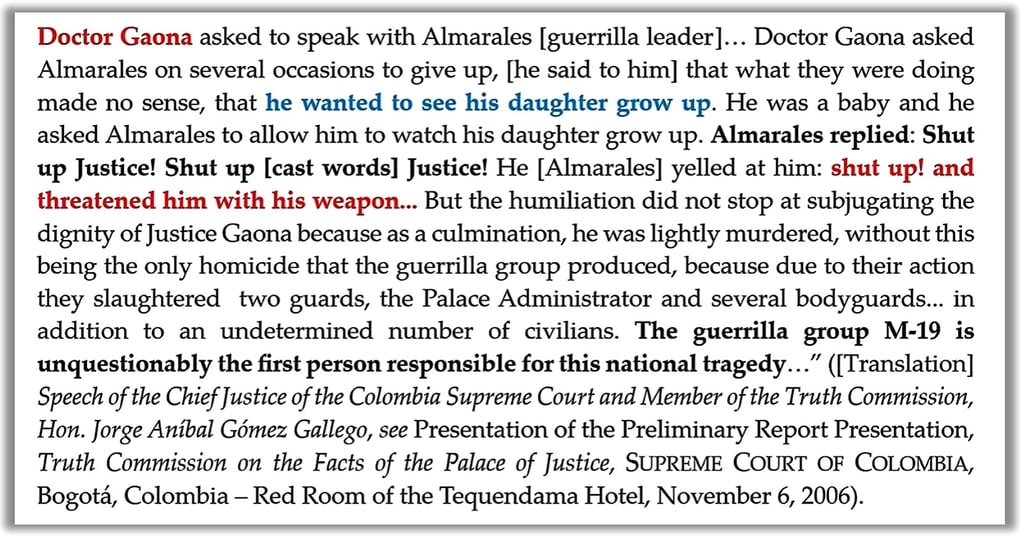

The Truth Commission established by the Supreme Court of Colombia described the human rights violations and crimes against humanity suffered by Justice Manuel Gaona Cruz at the hands of the M-19 guerrillas as "outrages against the dignity of Justice Gaona" (see Preliminary Report of the Truth Commission by Chief Justice, Hon. Jorge Anibal Gomez Gallego in Presentación del Informe Preliminar de la Comisión de la Verdad por el Magistrado y Ex Presidente de la Corte, Jorge Aníbal Gómez Gallego, CORTE SUPREMA DE JUSTICIA 2006; see video in MGC Death - Evidence).

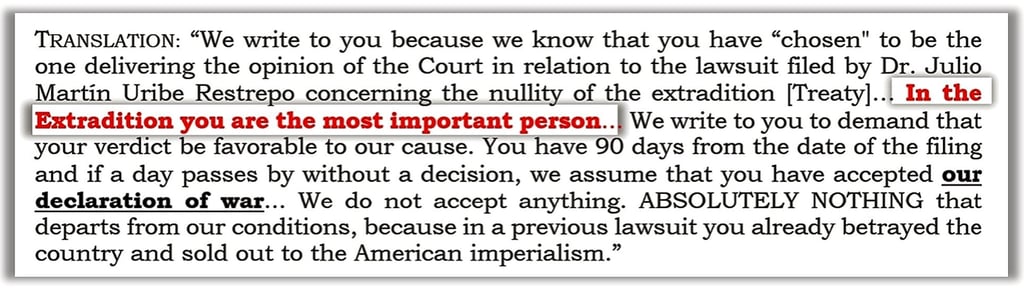

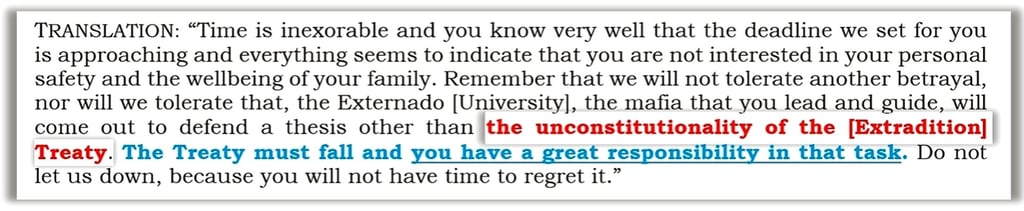

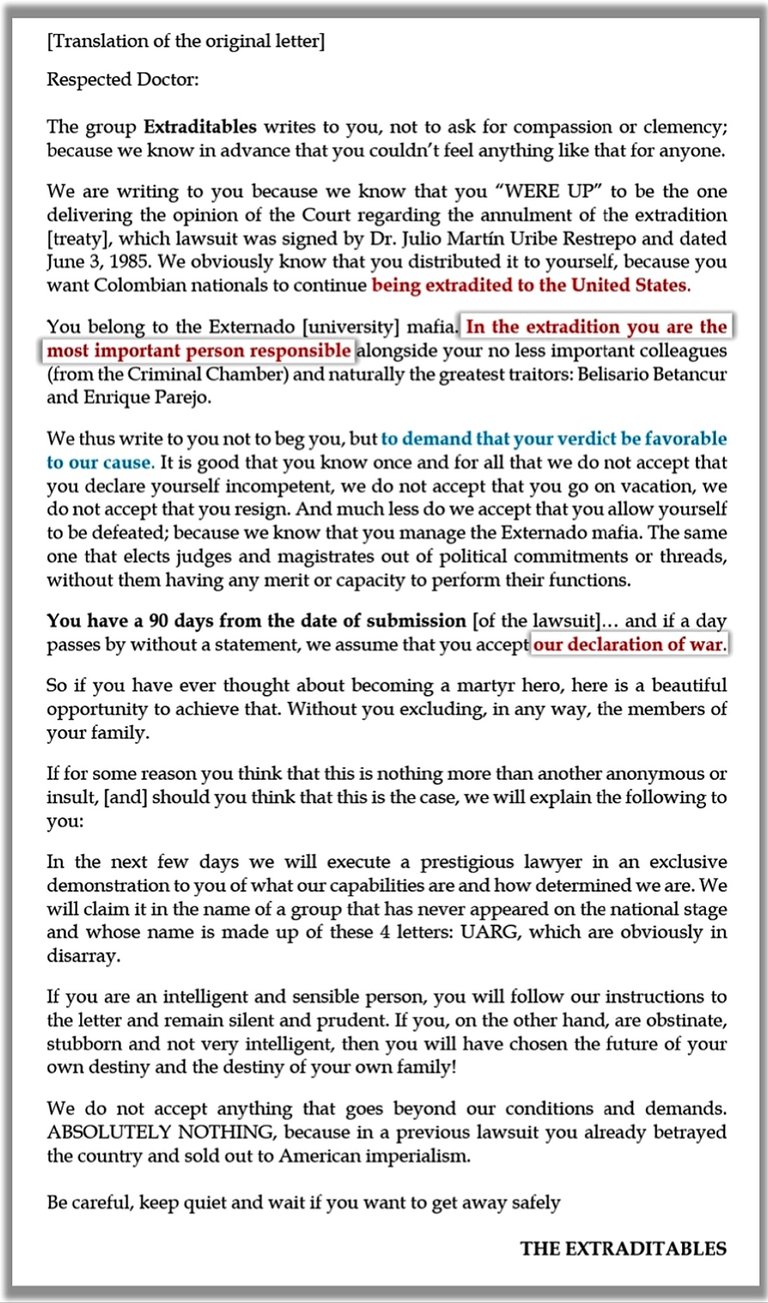

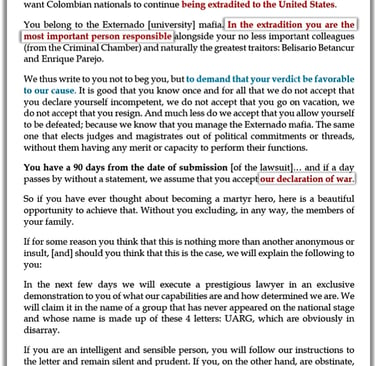

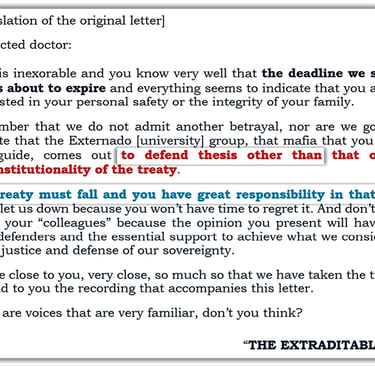

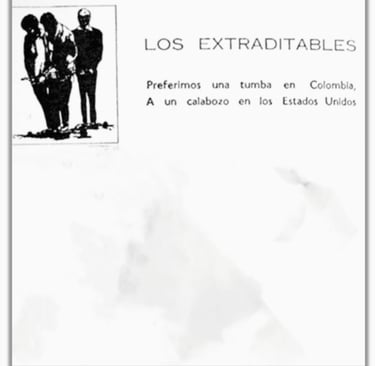

On June 5, 1985, Pablo Escobar's Attorney, Julio Martin Uribe Restrepo, filed a complaint before the Supreme Court of Colombia challenging the constitutionality of the law approving the Extradition Treaty between Colombia and the United States of America (Law 27 of 1980). On June 28, 1985, the complaint arrived at the chambers of Justice Manuel Gaona Cruz. On Monday, August 5, Manuel Gaona Cruz received the first letter from the Extraditables (i.e., Pablo Escobar and the Medellín Drug Cartel), which transcribed:

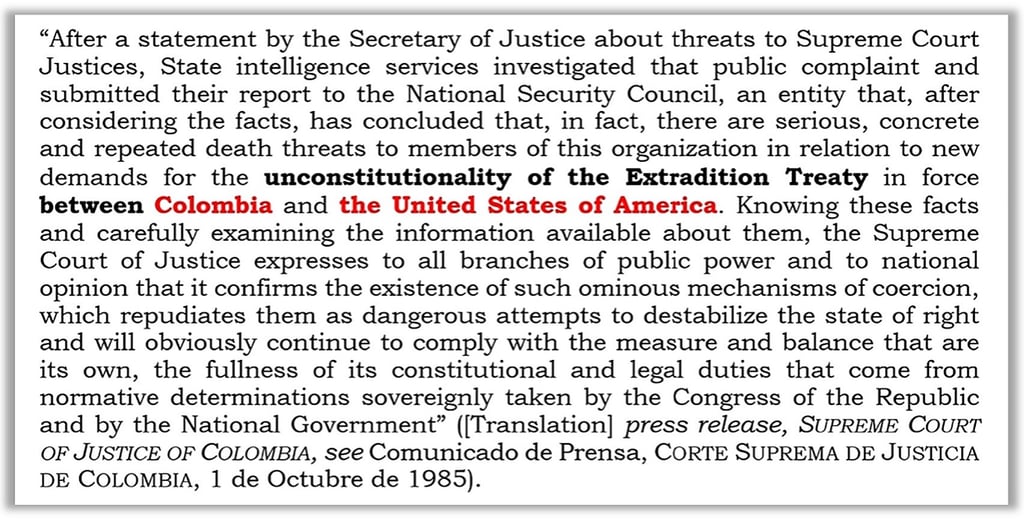

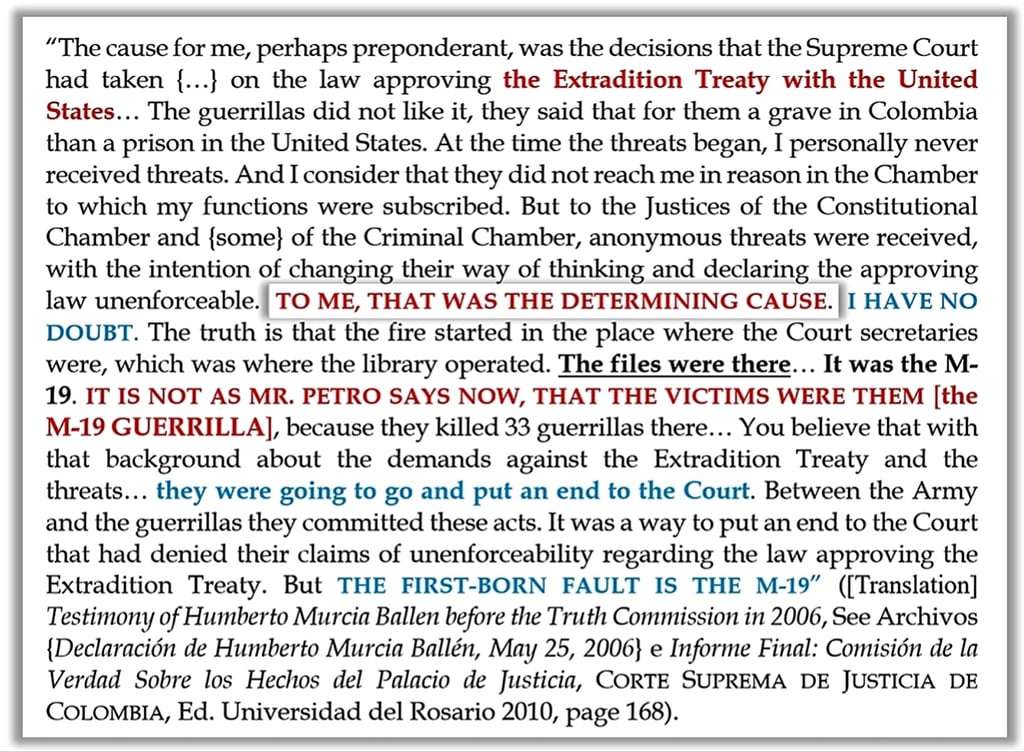

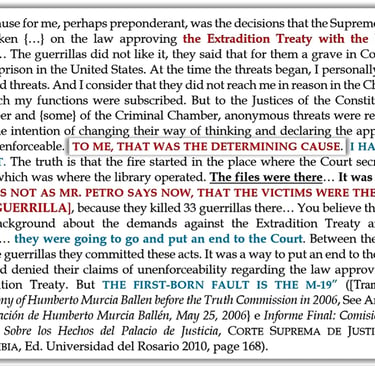

Despite the security measures arranged to protect Justice Gaona and his family, the telephone interceptions at his residence continued throughout September. To discuss the report from the National Security Council regarding the risks and threats posed by the group "los Extraditables" led by Pablo Escobar against the Justices of the Constitutional Chamber and the Chief Justice, a meeting was held on Monday, September 30, 1985, at the Military Club. Those in attendance were the Justices of the Constitutional Chamber Manuel Gaona Cruz and Carlos Medellín Forero, the Chief Justice Alfonso Reyes Echandía, the Secretary of Interior Jaime Castro, the Secretary of Justice Enrique Parejo Gonzáles, the Director of the Administrative Department of Security (DAS) General Miguel Maza Márquez, and the Director of the National Police General Víctor Delgado Mallarino. The following day, on Tuesday, October 1, 1985, the Supreme Court of Justice of Colombia issued a press release informing the public about the threats from drug cartels related to the motion of unconstitutionality against the law approving the Extradition Treaty between Colombia and the United States, which was being considered by the Court. The constitutional review of the law was assigned to Justice Manuel Gaona Cruz.

His doctoral dissertation on Colombian and Latin American Presidentialism was lauded by the Sorbonne University of Paris 1 with its highest academic honor, Summa Cum Laude. Manuel Gaona Cruz is one of the very few foreigners and the sole Colombian to appear on the list of the Sorbonne’s most illustrious alumni, having received distinctions from both the Government of the Republic of France (with a Diplôme d'État) and the Sorbonne University (with the highest honorable mention Très Bien). This esteemed list also includes figures such as Thomas Aquinas, Maximilien Robespierre, Honoré de Balzac, Alexis Henri Tocqueville, Marie Curie, Pierre Curie, Louis Pasteur, Michel Foucault, and Alfred Binet. Beside the year 1970, the reference, "Manuel Gaona Cruz, Colombia", is etched in stone.

In addition to the human rights atrocities, the violations of the most basic principles of International Humanitarian Law, and the crimes against humanity committed against Justice Manuel Gaona Cruz during his kidnapping and assassination at the hands of the M-19 guerrillas, with his passing, the nation lost one of his most brilliant jurists, who for many, was the greatest expert on Constitutional Law in Colombia (see Diana

In 2022, Externado University held a ceremony to celebrate the victory of the former leader of the M-19 guerrilla Gustavo Petro Urrego in the presidential elections. At the event, the President of Externado University, Mr. Hernando Parra Nieto addressed the honoree before hundreds of students, saying: "Doctor Gustavo Petro, you are an illustrious son of Externado" (See complete speech and full ceremony at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=loj6_r89rmU).

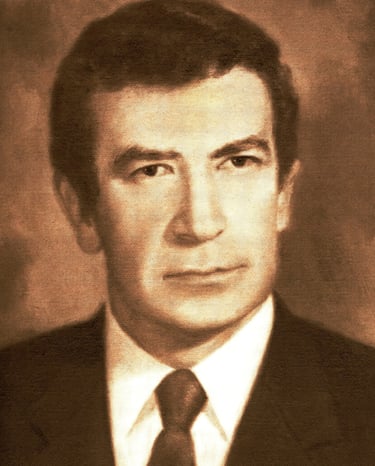

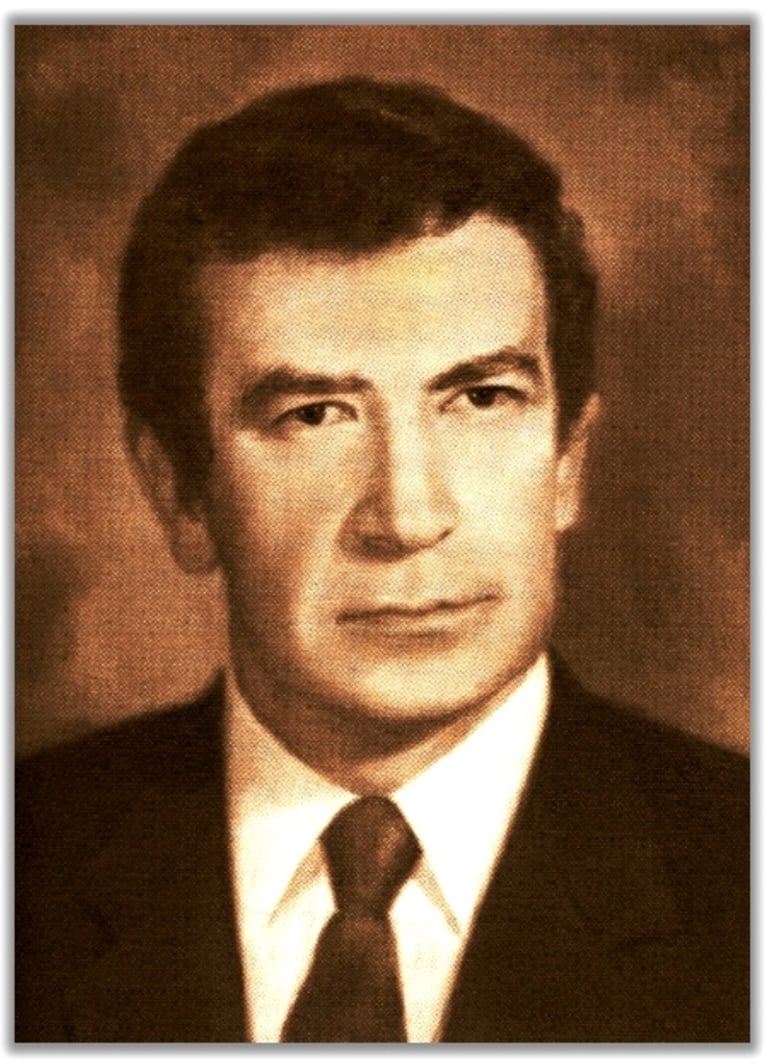

Manuel Gaona Cruz was the Chief Justice of the Constitutional Chamber (1984) and Justice of the Supreme Court of Colombia (1980-1985). He is recognized as one of the most brilliant and influential constitutionalists in the history of the country. His jurisprudence has transcended constitutional doctrine in Colombia and other countries in the region. His work as constitutional lawyer and his scholarly contributions as constitutional law professor were pivotal in the history and development of the Colombian constitutional system. The depth of his thought, the humbleness of his character, and the devotion to his academic work both as professor and as university president are remembered with profound appreciation by the thousands of students he educated from various universities and generations. His work as Under Secretary of Justice of Colombia and his fight against drug cartels in Colombia have also been recognized by judges, attorneys generals prosecutors, and international organizations. In 1996, the President of Colombia awarded Manuel Gaona Cruz the nation's highest civilian honor, the Order of Boyacá (Grand Cross, in memoriam) for his merits and his service to his country.

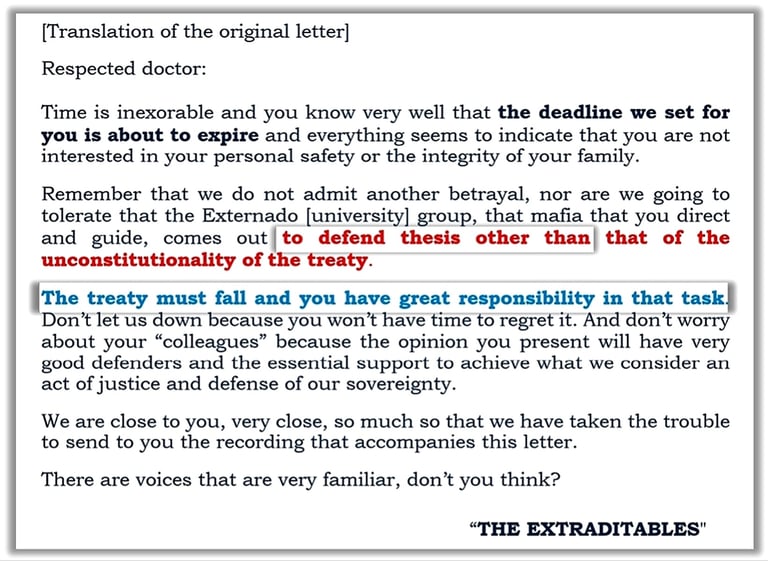

Following multiple bomb threats to his residence, surveillance of his family, phone calls, and audio cassettes with intercepted conversations of his children, on Sunday, September 1, 1985 and, while having breakfast with his wife and children, Justice Manuel Gaona Cruz received a second letter from Pablo Escobar signed by the group "los Extraditables" [The Extraditables]. In the letter, the Extraditables warned him not to defend his thesis on the constitutionality (the intermediate thesis) of the law approving the Extradition Treaty (see Pablo Escobar's and the Medellín Cartel's Second Letter to Justice Manuel Gaona Cruz in MGC Death – Documentary Evidence: Threats to Justice Manuel Gaona Cruz; see also the letter in Informe Final: Comisión de la Verdad Sobre los Hechos del Palacio de Justicia, CORTE SUPREMA DE JUSTICIA DE COLOMBIA, Ed. Universidad del Rosario 2010, page 315).

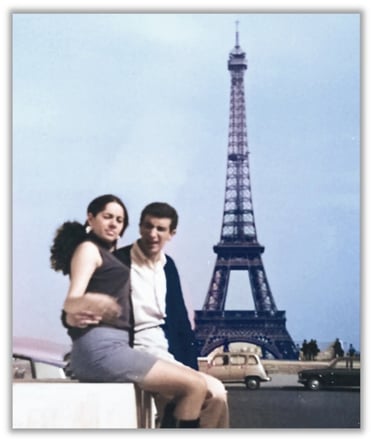

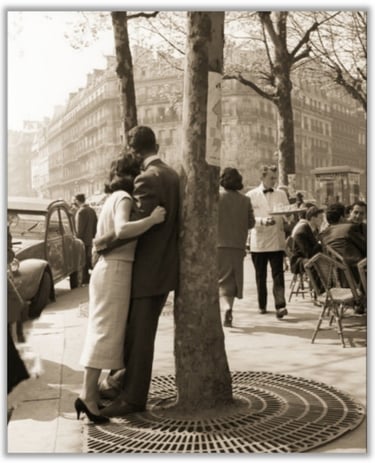

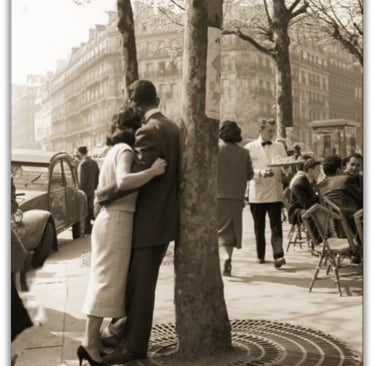

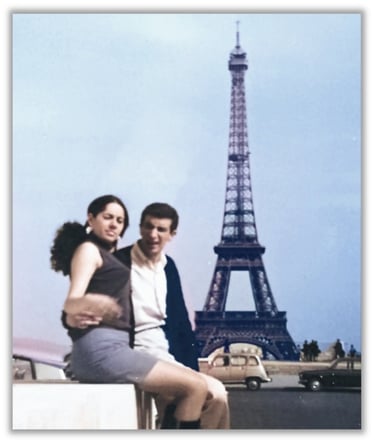

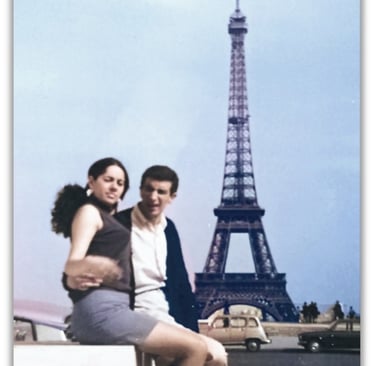

Manuel and his wife Marina Paris 1967

In addition to the notable influence of his constitutional and public law professors, Georges Vedel, Maurice Duverger and Georges Burdeau, Manuel and his wife experienced the protests of May 68 in Paris, along with the cultural transformation of French society following the emerging ideological debate between structuralists and existentialists in the 1960s.

Sorbonne University - Paris 1

Letter from Pablo Escobar and the Medellín Drug Cartel to Justice Manuel Gaona Cruz (see full letter in MGC Death – Documentary Evidence – First Letter from the Extraditables; see also letter published in the Supreme Court's Truth Commission Final Report, id., Informe Final: Comisión de la Verdad, page 315).

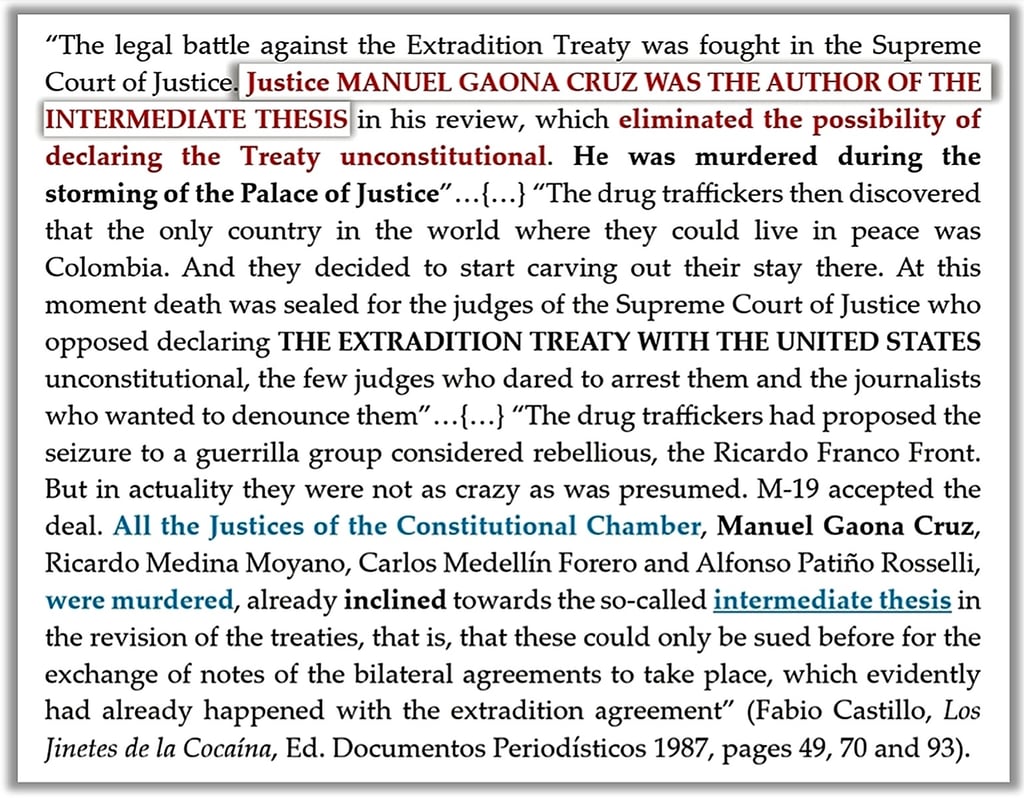

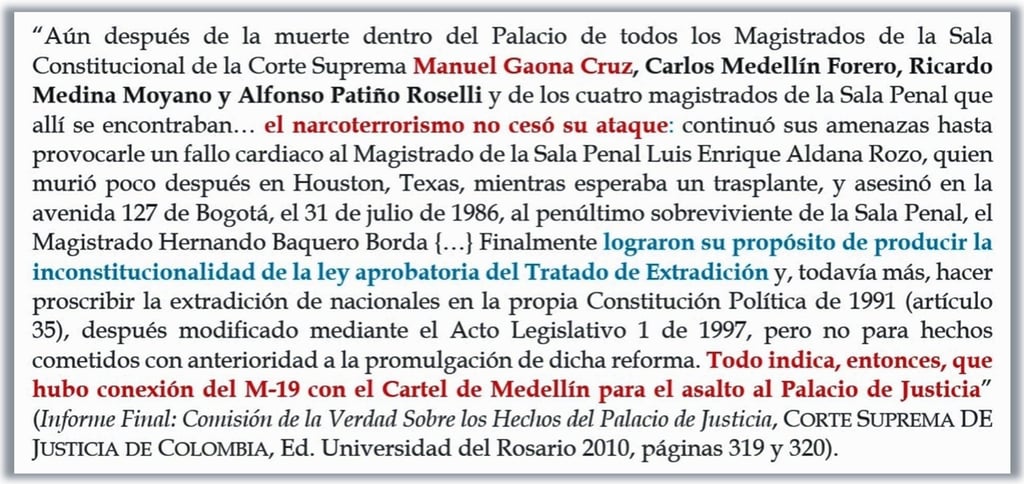

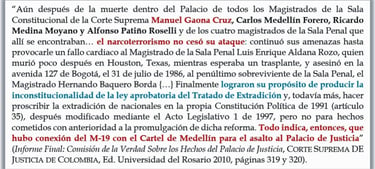

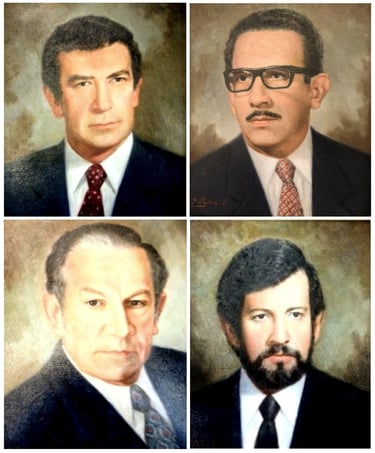

After the assassination of all the justices who comprised the Constitutional Chamber of the Court (Manuel Gaona Cruz, Carlos Medellín Forero, Ricardo Medina Moyano, Alfon Patiño Rosselli), the attack on the Palace of Justice in 1985, and subsequently, on Justice Hernando Baquero Borda in 1986, Pablo Escobar finally succeeded in getting the new Supreme Court of Justice, under intimidation, to declare the Extradition Treaty between Colombia and the United States unconstitutional eleven months after the guerrilla takeover in December 1986 (see Supreme Court's Truth Commission Final Report, Id., Informe Final: Comisión de la Verdad, pages 163 and 319; see also Fabio Castillo, Los Jinetes de la Cocaína [The Cocaine Riders], EIE 1987, pp. 48 and 70-73; Full Statement of the U.S. Ambassador to Colombia, Charles Anthony Gillespie Jr. in MGC Death - Crime Motive: Pablo Escobar, the Extraditables, and the M-19 guerrillas).

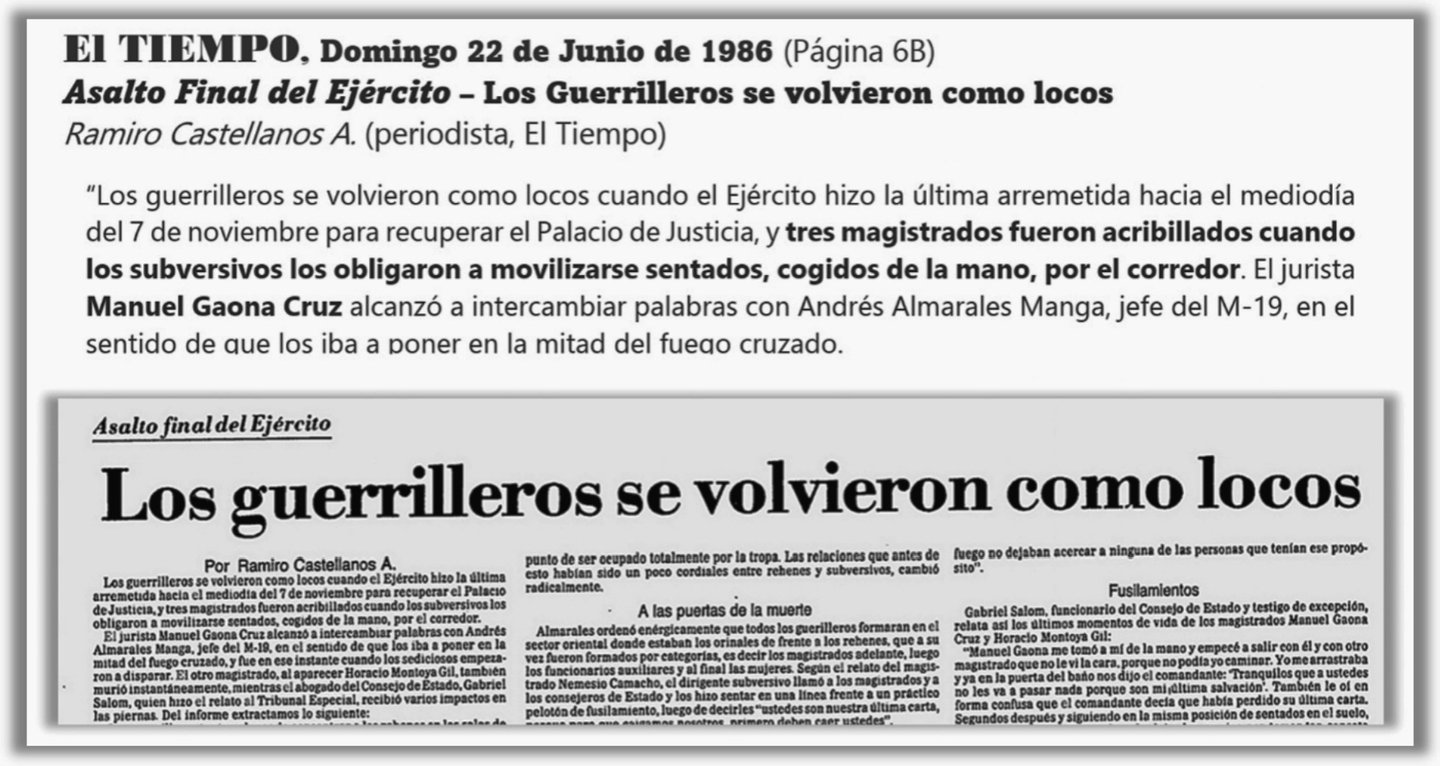

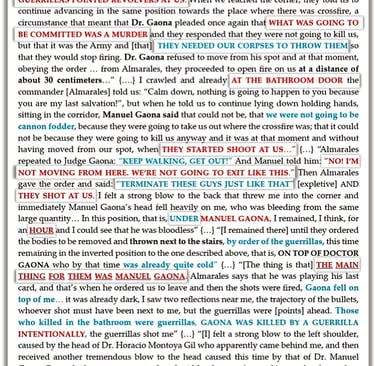

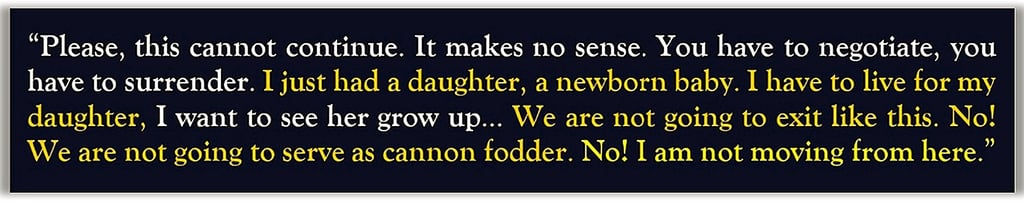

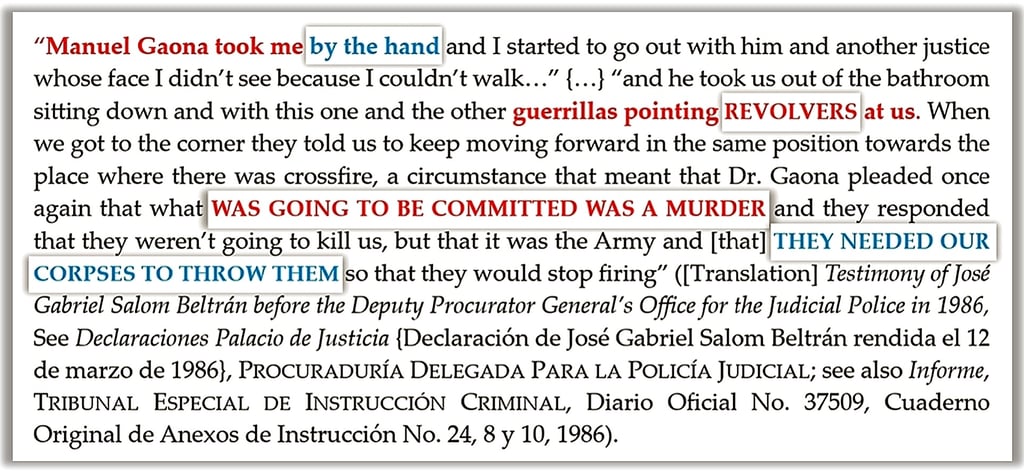

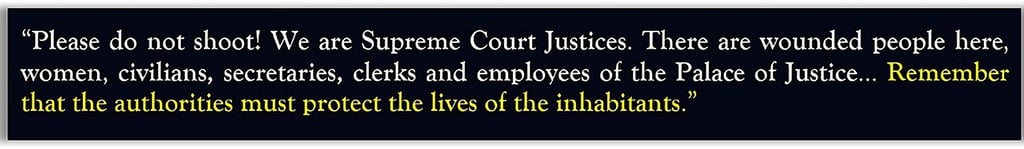

Last words of Supreme Court Justice Manuel Gaona Cruz to guerrilla leader Andres Alamarales Manga, on Thursday, November 7, 1985, before being executed by M-19 guerrillas inside the Palace of Justice (see MGC Death – Testimonial Evidence; see also Statement of Jose Gabriel Salom Beltran before the Deputy's Public Ministry Office for Judicial Police in Declaración de José Gabriel Salom Beltrán rendida el 12 de marzo de 1986, PROCURADURÍA DELEGADA PARA LA POLICÍA JUDICIAL; see also Informe, TRIBUNAL ESPECIAL DE INSTRUCCIÓN CRIMINAL, Diario Oficial No. 37509, Cuaderno Original de Anexos de Instrucción No. 24, folios 1, 8 y 10, 1986; Informe Final: Comisión de la Verdad Sobre los Hechos del Palacio de Justicia, CORTE SUPREMA DE JUSTICIA DE COLOMBIA, Ed. Universidad del Rosario 2010, page 166; Ramiro Castellanos A., Asalto Final del Ejército : Los Guerrilleros Se Volvieron Como Locos [The Army's Final Assault: The Guerrillas Went Crazy], EL TIEMPO, June 22, 1986 {page 6-B}.

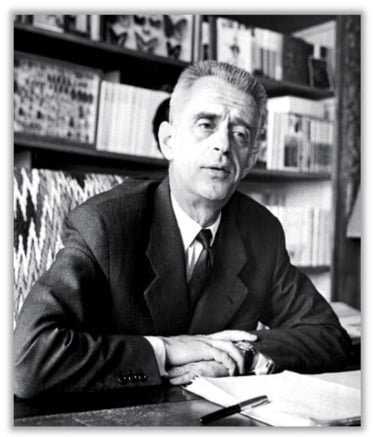

Uriel Alberto Amaya Olaya 30th Criminal Investigation Judge of Bogota (1989)

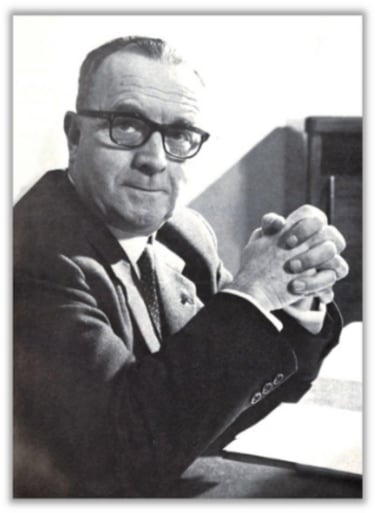

Charles Anthony Gillespie Jr. (Right) U.S. Ambassador to Colombia 1985-1988

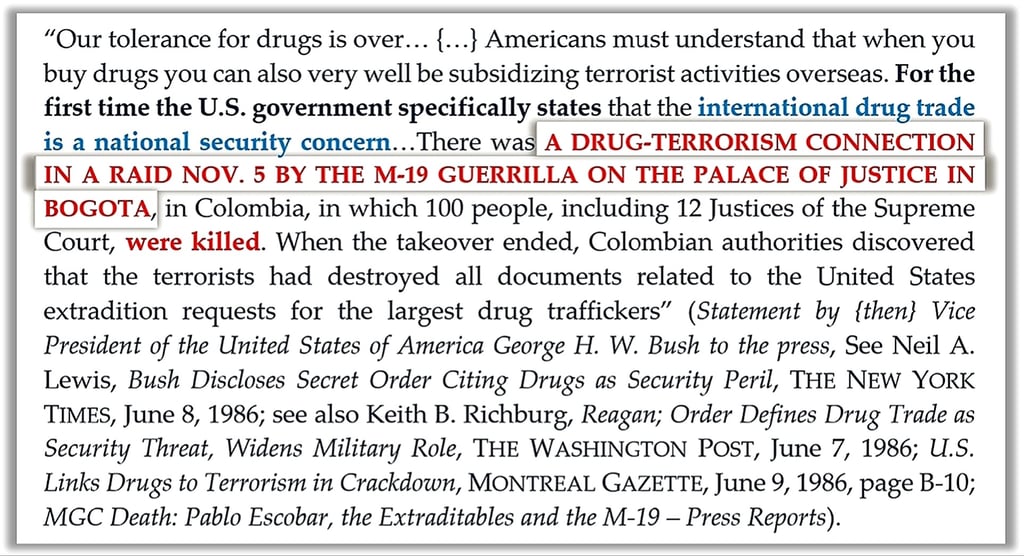

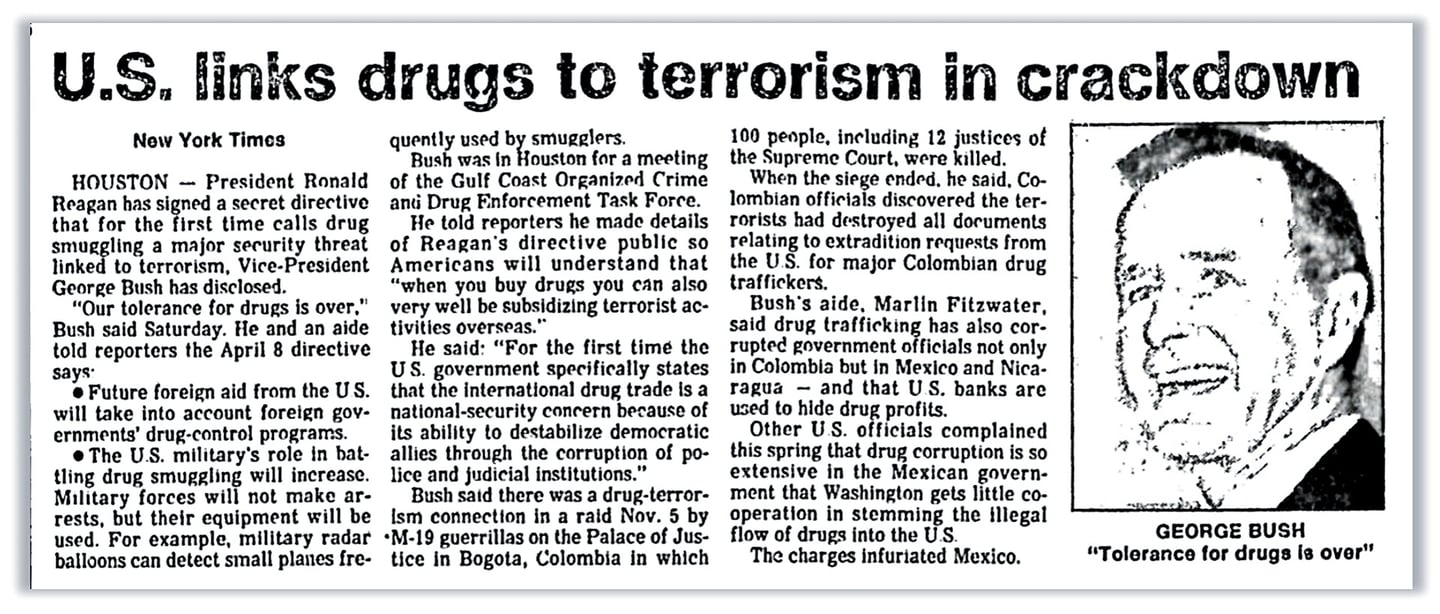

For his part, the President and then Vice President of the United States, George H. W. Bush, stated:

George H. W. Bush United States President 1989 -1993 Vice President 1981 - 1989

Jorge Anibal Gomez Gallego Chief Justice Colombia Supreme Court 2003-2004 Member of the Truth Commission 2006 - 2010

Supreme Court of Justice of Colombia November 6, 1985

Externado University of Colombia Hernando Parra Nieto (Left, University's President) and Gustavo Petro (Right, Former Leader of the M-19 Guerrilla and president-elect), July 26, 2022.

Despite the gesture and the welcome he received at the university where five of the eleven assassinated justices worked as law professors, the former guerrilla leader of the M-19 never acknowledged the terrorist group's responsibility for the crimes committed in the attack on the Palace of Justice, nor for the crime against Justice Manuel Gaona Cruz. In 2024, in fact, the guerrilla leader and (now) president of Colombia, Gustavo Petro Urrego, decorated his M-19 guerrilla comrades during the anniversary of the Palace of Justice takeover, calling them "examples of peace" (see Frank Saavedra, "El Presidente Petro Condecoró a Exguerrilleros del M-19 Junto a Miembros de las Fuerzas Armadas: 'Es un ejemplo de paz'," INFOBAE, November 5, 2024).

Voice and Teachings of Justice Manuel Gaona Cruz

Manuel Gaona Cruz led the group of lawyers who filed a lawsuit before the Supreme Court of Justice of Colombia against Legislative Act No. 1 of '79, a decision which led to the Fall of the 1979 Constitution (see Manuel Gaona Cruz & Antonio José Cancino, La Caída de la Reforma Constitucional de 1979, Ed. TEMIS 1981). His defense of the principles of Separation of Powers and the Independence of the Judiciary that caused it transcended not only as constitutional doctrine in Colombia, but as a reference in Comparative Constitutional Law in other countries (see Marisol Peña Torres, "La Caída de la Reforma Constitucional de 1979", REVISTA CHILENA DE DERECHO, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, Vol. 10, 1983, pages 231-242). The influence of his legal opinions as Supreme Court Justice has been studied and highlighted by several generations of Colombian jurists. Among his most cited opinions are the doctrine of preliminary constitutional review, which was later adopted in the 1991 Constitution of Colombia (Article 241, Paragraph 10, "Jurisdiction of the Constitutional Court," POLITICAL CONSTITUTION OF 1991), granting the thereby created Constitutional Court the power to review international treaties and laws approving them before their ratification, as well as his intermediate doctrine (based on Public International Law, Comparative Constitutional Law, and Colombian Constitutional Law) which prevented the declaration of unconstitutionality of the law approving the Extradition Treaty between Colombia and the United States of America between 1982 and 1985. His most famous legal writings include, among others, the respect for freedom of the press and its sources, the respect for individual liberties and human rights in Colombia, the independence of the judiciary, the constitutional limitations on police power, the immutability of judicial rulings, the review and reform of the Constitution, the scope of the public action of unconstitutionality, the constitutionality of economic emergency decrees, and the constitutional limits on the state of siege and other states of exception in times of peace. At an international level, his doctrines on Latin American presidentialism and comprehensive and parallel constitutional review in Colombia—which Professor Gaona categorized as "the most complete in the West and, therefore, in the world" (Manuel Gaona Cruz, Control y Reforma de la Constitución en Colombia, MINISTERIO DE JUSTICIA DE COLOMBIA 1988, Tomo II, page 72)—became references in Comparative Constitutional Law (see Julio Cesar Ortiz, "El Control Constitucional en Colombia", BOLETÍN MEXICANO DE DERECHO COMPARADO, Universidad Autónoma de México UNAM, No. 71, 1991, pages 481-516; Allan R. Brewer-Carias, "El Sistema Mixto o Integral de Control de Constitucionalidad en Colombia y Venezuela", REVISTA TACHIRENSE DE DERECHO, Universidad Católica del Tachira, No. 5-6, 1994, pages 111-164; Jorge Alejandro Amaya, EL CONTROL DE CONSTITUCIONALIDAD, Astrea Argentina, 2015).

In response to his service as Director of the Department of Public Law and as a distinguished professor of Constitutional Law and the Theory of State, on the one hand, and in consideration to the request made by the students of School of Law and by the then President Fernando Hinestrosa to the Justice's widow, the body of Manuel Gaona Cruz was held for two days in the main auditorium of Externado University on November 8 and 9 of 1985.

This work has been published in Spanish, English, and French and it is the result of several decades of research. This research was directed by Professor and son of Justice Manuel Gaona Cruz, J. Mauricio Gaona. Our work was supported by historians, anthropologists, pathologists, criminologists, ballistics experts, forensic technicians, lawyers, architects, IT professionals, and field researchers in Colombia, the United States, and France. This website and the following research are dedicated to the loving memory of Manuel Gaona Cruz and to the young people in whom we entrust the truth, the history, the sacrifice and the legacy of a truly remarkable jurist and human being. We present this work to the youth in search of the truth with a message beyond our time. The life and death of Manuel Gaona Cruz are prologues. Both the perpetrators of the unjustifiable and the people and organizations that benefited from the impunity of his crime and the manipulation of the truth forgot an indelible premise of history that is present in all crimes against humanity: victims do remember.

All rights reserved © J. Mauricio Gaona - Foundation Manuel Gaona Cruz - 2025.

Justice Manuel Gaona Cruz 1985

Before leaving for France, Manuel proposed to his neighbor, Marina, whom he had known since childhood. Manuel Gaona Cruz departed from the port of Cartagena de Indias for Europe in late June 1966. The sea voyage lasted a little over a month, and he was accompanied by his legal theory professor, Luis Fernando Gómez Duque, who used to jokingly recall his first exchange with his student on the boat: "I remember I told him, 'Hey Manuel! You've been standing there for more than an hour now. You're going to catch a cold, and it's drizzling out there. Don't tell me it's the first time you've seen the sea.'" Marveling, wet, and with a slight smile, Manuel looked at him and replied: "It's my first time for everything." Upon arriving at the port of Cannes in August, Manuel and his professor went their separate ways. One went to Paris, while the other went to Germany. Before saying goodbye with a heartfelt hug, the professor told his student: "This is my train, and that one over there is yours. That train takes you to Paris, which is your final destination. Although, knowing you as I do, something tells me you will go farther. Take care, and say hello to Robespierre for me." After learning he was admitted to the Sorbonne's Doctoral School, Manuel and Marina met a few months later in Paris, where they lived for five years. From then on, they were together and started a family with their children, Gabriel, Mauricio, Manuel, and Juliana.

Despite rumors from alleged hearsay witnesses regarding the supposed departure of Manuel Gaona Cruz from the Palace of Justice and his subsequent execution at the hands of the Army, and notwithstanding the request made by Justice Gaona Cruz' sons to investigate human rights violations committed by both the M-19 guerrillas and the Army—including said rumors—the Prosecutor's Office could not confirm such rumors, for which it refrained from issuing a resolution of accusation regarding the alleged execution of Justice Manuel Gaona outside the Palace of Justice. In 2023, former Deputy Prosecutor Angela Buitrago was nominated for Attorney General by the president of Colombia and former leader of the M-19 guerrilla, Gustavo Petro Urrego. In 2024, she was appointed Secretary of Justice in Petro's Government. In spite of her affiliation and closeness to the government, the investigation conducted by Deputy Buitrago had an undeniable legal and historical merit in terms of human rights and, more particularly, in relation to the group of people who disappeared during the recapture of the Palace of Justice, which eventually led to the criminal responsibility of the Army's operational command.

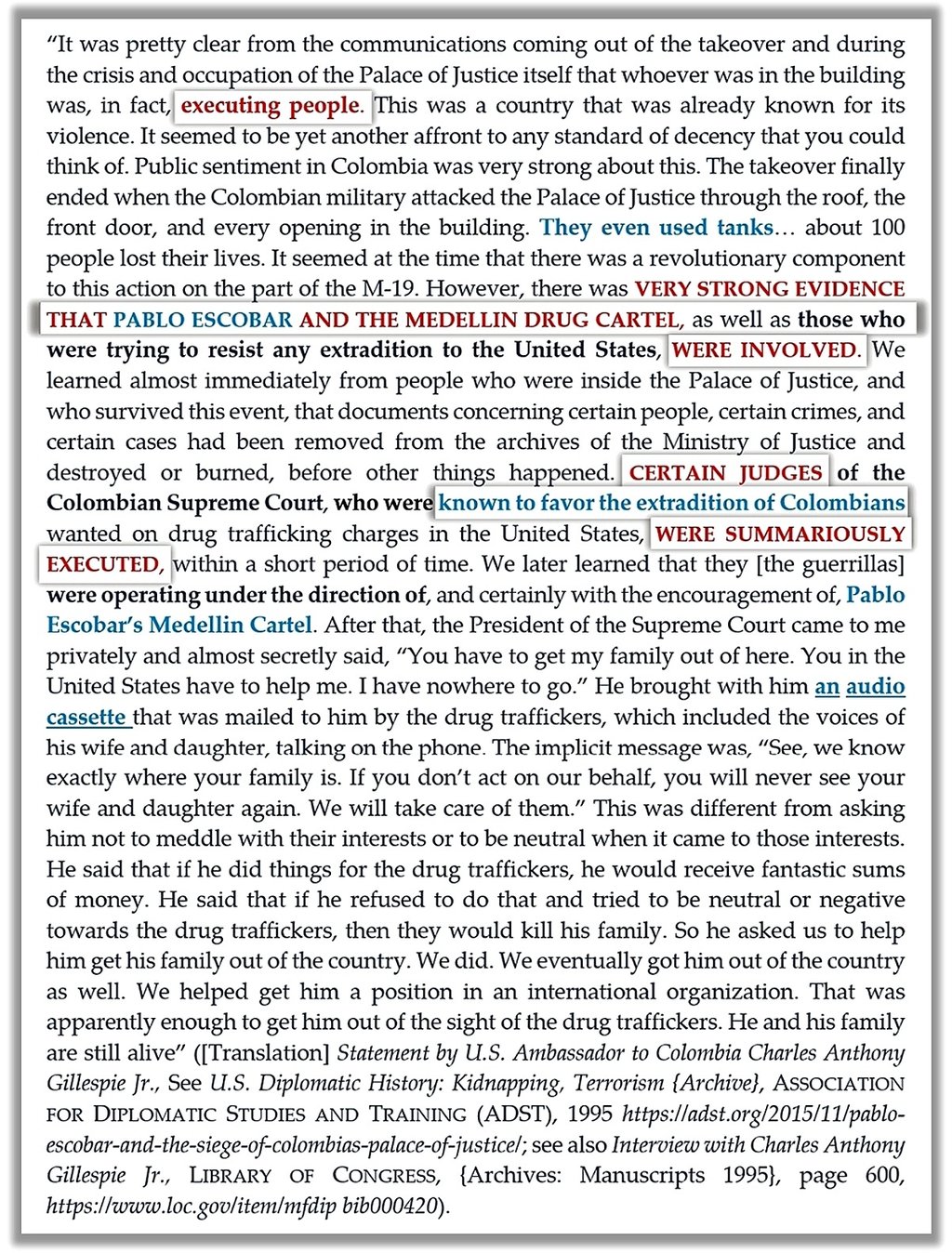

Despite rumors promoted by people with judicial, economic, political and bureaucratic interests—aimed at distancing the M-19 guerrillas from Justice Manuel Gaona Cruz' assassination and at erasing from the collective memory of Colombians the criminal relationship between the M-19 and drug trafficking in the attack on the Palace of Justice (see MGC Muerte – Rumores Sobre el Homicidio del Magistrado Manuel Gaona Cruz)—the United States government never had any doubt about the execution of Justice Gaona Cruz at the hands of the M-19 guerrillas, nor about the criminal conspiracy that existed in the takeover of the Palace of Justice in Colombia between the Medellín Cartel, Pablo Escobar, and the M-19 guerrillas. The statement issued by the United States Ambassador to Colombia in 1985, Charles Anthony Gillespie Jr., which is kept in the Library of Congress and in the historical archive of the U.S. Department of State, is part of that nation's public and diplomatic record. On this matter, the U.S. Ambassador to Colombia declared:

Ongoing efforts to erase from Colombia's collective memory the crimes against humanity and the human rights violations committed during the 1985 Palace of Justice attack continue. The 2025 propaganda film November, produced by television commercial director Tomas Corredor, brazenly promotes the image of M-19 guerrillas as victims of the siege, completely sanitizing the atrocious crime committed against Manuel Gaona Cruz while twisting the Justice's own words to portray him as an ally of his assassins. Cynically cashing in on one of the greatest tragedies in Colombian history and the memory of one of its most well-known victims, the film fundamentally distorts Manuel Gaona Cruz’s words and actions, misrepresenting his personality, moral integrity, and the character known to thousands of his students and colleagues. To edit out human rights violations and rewrite the words of victims is an assault on the history of this holocaust. Today, some television producers are working at full speed to rewrite Colombia’s collective memory through a blockbuster aimed at glorifying the most barbaric actions, enticing the youth to follow their path, and erasing the crimes against humanity that were committed there.

LIFE

FIRST YEARS

Manuel Gaona Cruz was born on May 15, 1941, in the city of Tunja, in the Department of Boyaca, Colombia. His family was of humble origins, with his parents, Virginia Cruz and Manuel Gaona, working in textile production. As the oldest of ten siblings, Manuel was given the responsibility from a very young age to study and work simultaneously to help support his family. As a child, Manuel would often accompany his father on his trips through the towns of Boyaca, selling textiles used to make sacks, blankets, and ruanas (similar to ponchos). His father, Don Manuel, used to recount that at the end of their route, his son would sit on the hood of his truck to observe the people passing through the main squares of the towns they visited. This more than once led his father to recall a memorable response from his son when he asked: "What are you doing sitting there, son? What are you looking at so intently?" Smiling, his son answered: "I was looking at the difference between the people with ruana and those with ironed ruana. It's a good thing Tunja is cold, because without a ruana, we wouldn't be able to tell them apart."

Manuel did his primary studies at the Public School of Tunja and his high school studies at the Camilo Torres School in Bogotá, after his father decided to move the family to the capital. Yet, when Manuel announced that he wanted to study law, his father, who disliked lawyers, vehemently opposed the idea, which eventually led to Manuel leaving home to pursue his dream of becoming a lawyer.

Among the books that most fascinated Manuel were: The Wall by Jean Paul Sartre, On the Genealogy of Morality by Friedrich Nietzsche and the 1953 classic, awarded by the French Academy of Language, French Language and Civilization Course, by Gaston Mauger. With this last book, Manuel taught himself French.

Virginia Cruz and Manuel Gaona Manuel Gaona Cruz' parents

Manuel Gaona Cruz First Communion 1949

Manuel Gaona Cruz Law degree graduation and swearing-in ceremony 1965

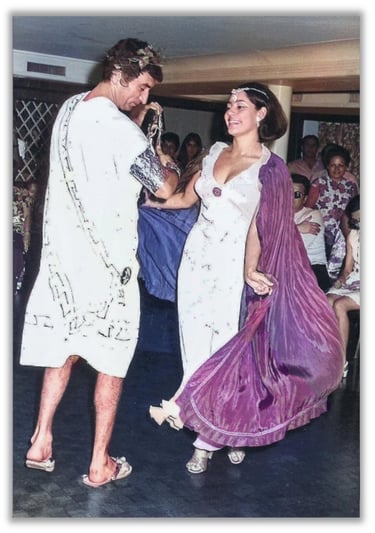

Years later, upon learning that his son was about to graduate with the highest honors from Externado University, father and son reconnected. A few months later, moreover, upon learning that the Government of France had granted his son an honorary scholarship to complete a Ph.D. in law at the Sorbonne University in Paris, Don Manuel organized a memorable party to celebrate his son's graduation, scholarship, and upcoming trip to France. Among the guests was his neighbor Marina, whom his son hadn't seen in several years. When Manuel saw Marina, he was captivated. They talked and danced for hours. That night, and without a formal courtship, Manuel proposed marriage to Marina and asked her to meet him a few months later in Paris. From that night on and until the end, Manuel and Marina were together.

Education and Life in Paris

Manuel Gaona Cruz graduated with honors and a law degree from Externado University in 1965. He later earned a summa cum laude (Mention d'honneur très bien) and a Ph.D. in Constitutional Law and Political Science from the Sorbonne University in Paris 1 in 1972. His doctoral thesis on Colombian and Latin American Presidentialism was lauded by the Government of the Republic of France and by the Sorbonne Doctoral School in 1970. His work was supervised by professors Georges Burdeau and Maurice Duverger.

After overcoming the distance with long love letters for six months, Manuel and Marina were married on January 6, 1967, and lived in an apartment on Rue Saint Antoine, very close to the Place de la Bastille in Paris. In their first years, the newlyweds enjoyed the splendor of the Parisian Bohème of the 60s, a scene inspired by the songs of Charles Aznavour, Yves Montand, Joe Dassin, and Jacques Brel, along with the French cinema movies of Alain Delon, Gérard Depardieu, Pierre Richard, Jean-Paul Belmondo, Brigitte Bardot, and Catherine Deneuve. They also encountered the ideological and cultural debate of the time between French existentialists and structuralists, shaped by Jean Paul Sartre, Michel Foucault, and Pierre Bourdieu.

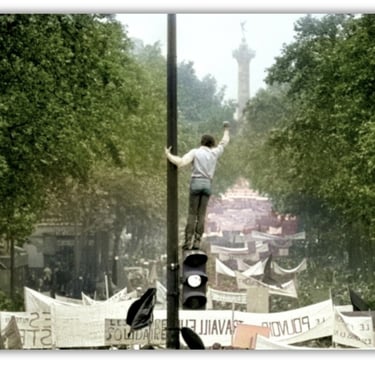

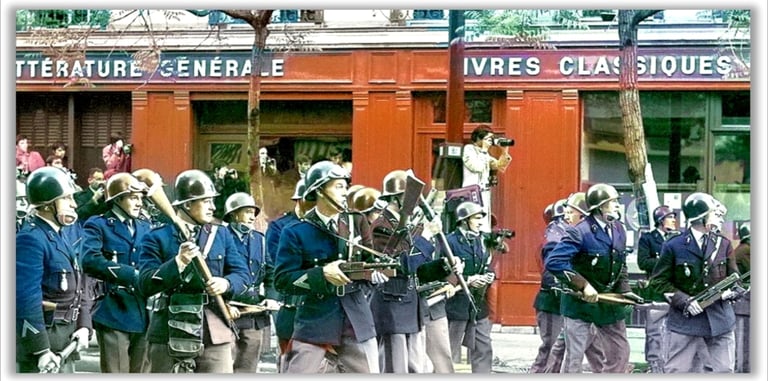

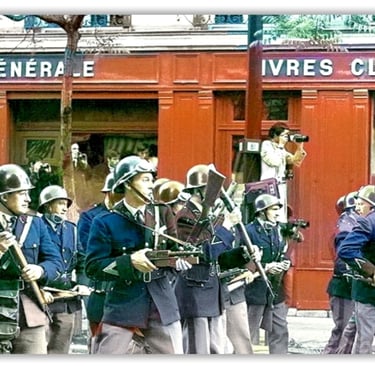

Manuel and Marina found themselves in the heart of the May 1968 student protests in Paris (« mai 68 ») when the forces led by the government of General Charles De Gaulle entered the Latin Quarter and took over the Sorbonne University facilities. Following the increase in street violence and the closure of public transportation, banks, and postal services, food scarcity became imminent. Manuel and Marina had no other option but to take refuge in their apartment and share a cup of coffee and a baguette each day to make their food rations last. The May Revolution led to political, social, and cultural change in France. Since then, the role and power of students have transformed the French educational system. After putting his name forward to represent foreign students in France, the young Colombian lawyer was elected President of the International Association of Foreign Students CIRCUFLAK in August 1968.

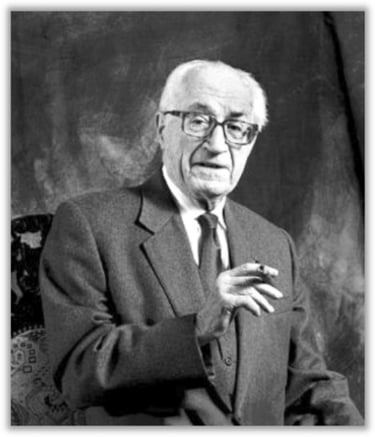

Manuel Gaona Cruz defended his doctoral thesis in the fall of 1970 before a jury of five professors, including three of the most legendary professors of the Sorbonne University: Georges Vedel (Member of the French Constitutional Council and the French Academy), Maurice Duverger (Professor Emeritus of the Sorbonne University), and Georges Burdeau (Honorary Professor of the University of Paris, author of the General Theory of the State and the ten-volume Treatise of French Constitutional Law; see La mort de Georges Burdeau: Analyse d'une étonnante modernité, LE MONDE, April 27, 1988). The defense of Manuel Gaona Cruz's Ph.D. dissertation lasted three and a half hours. At the end of his presentation and, in a symbolic gesture considered truly exceptional, the professors exchanged notes, looked at each other, and rose to applaud the candidate.

Manuel Gaona Cruz with his wife Marina in París 1966 – 1971

Student Protests at the Bastille Paris, May 1968

General De Gaulle's forces enter the Latin Quarter and capture the Sorbonne Paris, May 1968.

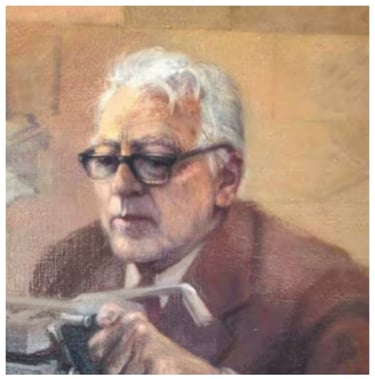

Goerges Vedel

Goerges Burdeau

Maurice Duverger

Professors of Manuel Gaona Cruz at the Sorbonne

Then, they announced their decision to award him the State Doctorate (Doctorat d'État) with the highest French academic distinction and the unanimous declaration of the thesis jury: Summa Cum Laude « Très bien, Monsieur Gaona! Très bien! » (Very good, Mr. Gaona! Very good!). Outside the professors' room, his wife Marina waited for him in her most beautiful dress with a bouquet of flowers. Upon hearing the applause, Marina stood up. When she saw her husband escorted out by his professors and heard the applause of the students who had gathered in the hallway after hearing the news, Marina, emotional and with tears in her eyes, ran to embrace her husband. According to what Manuel and Marina later told their children, that was "the best hug of our lives."

Teachings, Home and Personality

Manuel Gaona Cruz is remembered by friends and students as an exceptional, brilliant, and lively person who was deeply humble, very sociable, and pleasantly jovial. He enjoyed telling jokes and socializing with friends, colleagues, and family in his home. More than that, Manuel was an insatiable reader. His library occupied a primary place in his home and in his life. By 1985, Professor Gaona's library had more than 2,000 volumes in comparative constitutional law, history, philosophy and literature, along with a hundred vinyl records of great classical works that he used to listen to while writing. More than seventy percent of the books that made up his library were written in French and English. When his older children would ask him questions that required an extensive explanation, Manuel would hand them over two books: one with the answer and another with the grammar to understand the language in which it was written. For his older children, Manuel Gaona Cruz was always a teacher more than a father.

Manuel and Marina had four children: Juliana, Gabriel, Mauricio, and Manuel. Their daughter Juliana arrived toward the end of their lives, but she was undoubtedly their greatest joy and fascination. According to one of Manuel Gaona's dearest friends, Humberto Merchan, "Manuel's delight in having his daughter Juliana was contagious. He would go crazy with happiness every time his daughter learned or did something. Every time we saw each other, he would excitedly come into my office to tell me 'stories of the future' about the trips he wanted to take with his daughter and the things he wanted to teach her." Every night upon returning from the Court, Manuel dedicated a couple of hours to talking, playing with, and making his daughter laugh. Because of his personality and frankness, his son Gabriel was the one who made the Justice laugh the most.

De todas las caminatas que hicieron con su padre, la que sus hijos mayores más recuerdan eran las que solían hacer por el caribe Colombiano entre la ciudad de Santa Marta y un pueblo costero llamado Taganga. En una de sus últimas caminatas, Manuel le ensenó a sus hijos a caminar por la vida diciendo:

The Route of Life

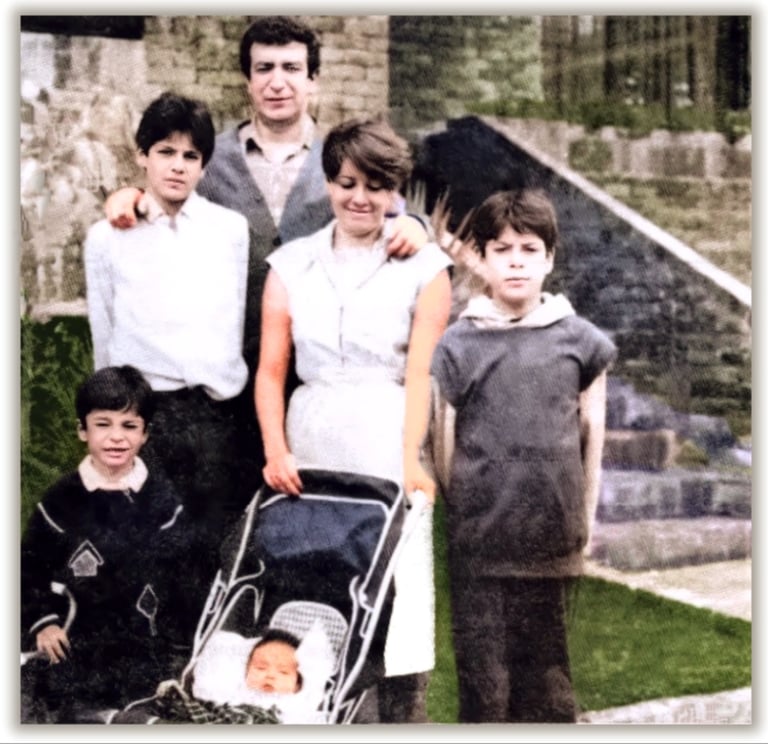

Justice Manuel Gaona Cruz's Family Last photograph of Manuel Gaona Cruz with his children, his baby, and his wife, taken in front of their home three months before the siege of the Palace of Justice. Septiembre 7, 1985.

Career in Colombia

The Under-Secretary of Justice and His Fight Against Drug Trafficking

General-Secretary of Colombia's Public Ministry

Upon returning to Colombia, Manuel Gaona Cruz joined the Office of the Attorney General as an Assistant Prosecutor. Soon, word of the brilliant young prosecutor who had just returned from France reached the then-Attorney General, Jesús Bernal Pinzón, who, after an interview, decided to promote him to an advisory lawyer in his office. Dozens of Colombians who served in the Attorney General's Office during that time still fondly and emotionally remember the personality, humility, and intelligence of Manuel Gaona Cruz. Attorney General Bernal Pinzón himself recounted on more than one occasion the promotion of his young advisor to Secretary General of the Attorney General's Office after asking him: “Doctor Gaona, what should I do? I need to appoint a Secretary General because the one I had left. The problem is it will only be for two months because my term is ending. Do you have a candidate?” — “Of course! Doctor Bernal, I have the exact person for you.” — “Who?” — “Well, me.” After meeting him and receiving excellent references from his predecessor and from delegate and assistant prosecutors, the new Attorney General, Jaime Serrano Rueda, ratified Manuel Gaona Cruz as Secretary General (See Oscar Alarcón Núñez, “La Vida y Tragedia de Manuel Gaona Cruz” in Estudios Constitucionales Manuel Gaona Cruz, MINISTERIO DE JUSTICIA 1988, Volume II, page 609).

Manuel Gaona Cruz served as Under-Secretary of Justice of Colombia during the administration of President Alfonso Lopez Michelsen and Secretary Cesar Gomez Estrada. During his tenure, Manuel Gaona Cruz was credited, among other things, with the development of the Notarial Statute and the Superintendence of Notarial and Registry, as well as the development of the first state policies related to the fight against drug trafficking and the production of drugs, psychotropic substances, and narcotics in Colombia (See Estudios Constitucionales Manuel Gaona Cruz, id., pages 600-609; see also Report of the International Narcotics Control Board, INTERNATIONAL NARCOTICS CONTROL BOARD (INCB) OF THE UNITED NATIONS, 1978, E/INCB/41, New York, 1978; Bruce M. Bagley, Colombia and the War Against Drugs, FOREIGN AFFAIRS, September 1, 1988).

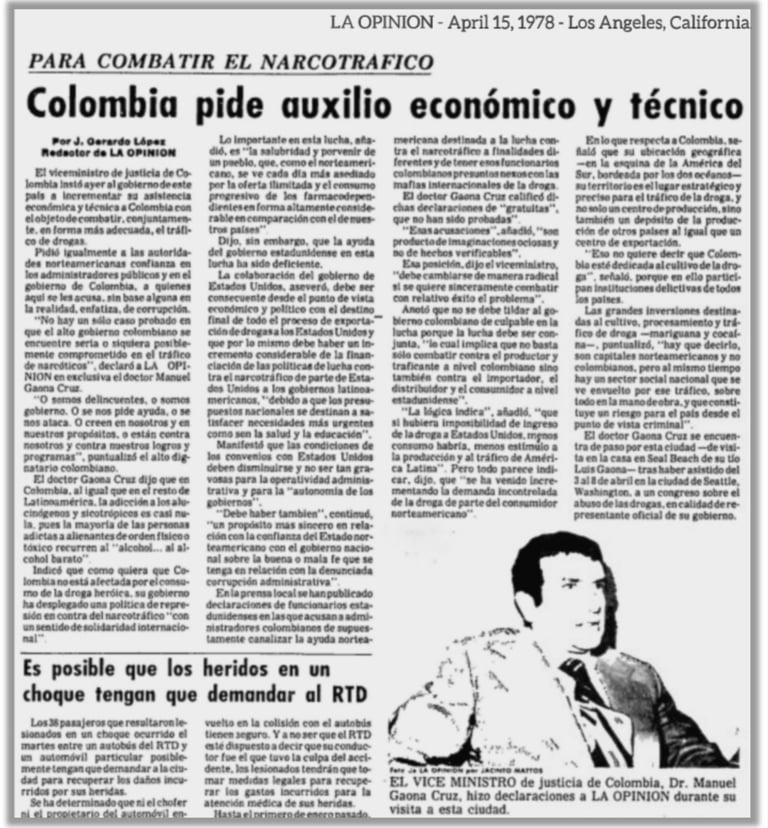

During the International Forum of Judges and Prosecutors held in Washington D.C. in 1978, and before officials from the United Nations and various countries, the Under-Secretary of Justice Manuel Gaona Cruz denounced the exponential growth of drug cartels in Colombia. He attributed this to the increase in drug use in Europe and North America, the lack of international mechanisms to combat drug trafficking, and the unprecedented rise of economic and political corruption in producer countries. In a subsequent visit to the United States, then Under-Secretary Gaona initiated the first process of judicial cooperation with the U.S. based on shared responsibility, while also requesting a technical and financial assistance package from American authorities to jointly fight drug trafficking as a global phenomenon. The newspapers LA Times, La Opinión, and The Herald (See To Fight Drug Trafficking Colombia Asks for Economic and Technical Aid, LA OPINION, April 15, 1978) reported on the Colombian Government's request through its Under-Secretary of Justice.

University President and Constitutional Law Professor

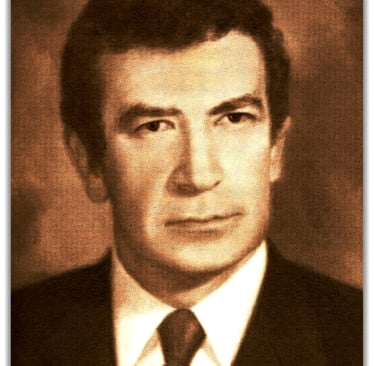

In 1976, the Mayor of Bogota appointed Manuel Gaona Cruz as President of the Francisco Jose de Caldas District University in Bogota, during one of the most convoluted periods in that university's history. The comprehensive restructuring that the young lawyer proposed to the Mayor was essential to save the university, reestablish order, integrate minorities, and promote a merit system for professors and students. In the words of Manuel Gaona Cruz's successor as rector of the university, Professor Jorge Rivadeneira Vargas:

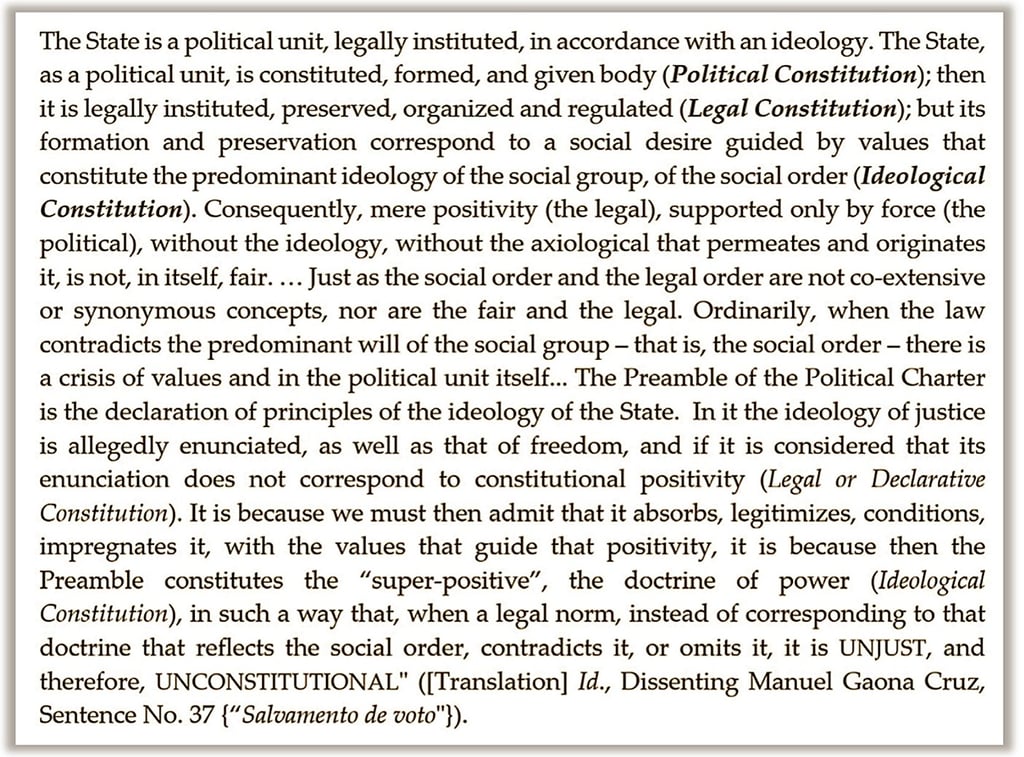

One of Professor Gaona Cruz's best students and disciples, Professor Rodrigo Uprimny Yepes, describes his teacher's constitutional philosophy as a conception of law that is at once sociological and axiological. Gaona believed that law in general and constitutional institutions in particular could not be understood outside of their social context, and that the raison d'être of any State is to protect individual liberties, not to restrict them. For this reason, he indicated that the Constitution must be interpreted as a guarantor of rights, not merely in its strictly normative sense, believing that "the Court protects the Charter, not the Charter the Court." He argued that respect for the law cannot precede the respect for life or human rights, and that the Constitution is not a norm per se, but rather a "tripartite" Constitution, that is: "political, legal, and ideological Constitution" (Uprimny, Rodrigo et al. “La Filosofía Constitucional del Profesor Gaona" en Estudios Constitucionales Manuel Gaona Cruz, MINISTERIO DE JUSTICIA 1988, Tomo I). For Gaona, in short, "constitutional norms are the institutional embodiment of a specific conception of the world," and their justification is found in the "axiological or evaluative aspect that explains the Constitution's raison d'être," from which our rights and most primary liberties are derived ( See Manuel Gaona Cruz, Ponencia: Congreso Internacional de Derecho Constitucional, Sao Pablo-Brasilia, Brasil, 1976; Manuel Gaona Cruz,. “La Reforma del 36”, REVISTA 6 DE NOVIEMBRE, No. 2, junio 1986, página 50).

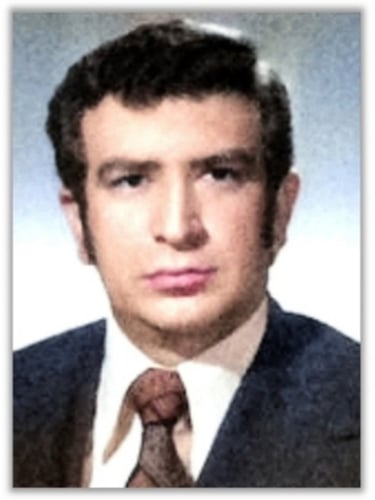

Chief Justice of the Constitutional Chamber and Justice of the Supreme Court of Colombia

Manuel Gaona Cruz was appointed as a Justice of the Court in July 1980 and as Chief Justice of the Constitutional Chamber of the Supreme Court of Colombia in 1984. The list of candidates nominated to replace his predecessor, the Constitutional Chamber's Justice Gonzálo Vargas Rubiano, was made of then-former Under-Secretary of Justice Manuel Gaona Cruz, former Mayor of Bogotá Bernardo Gaitán Mahecha, and Magistrate of the Council of State Humberto Mora Osejo. At 38 years of age, Manuel Gaona Cruz was victorious and was appointed by the Supreme Court of Justice.

The jurisprudence of Magistrate Manuel Gaona Cruz is extensive and highly varied. His rulings, clarifications, and dissenting opinions in Public Law, Constitutional Law, and International Law established very clear jurisprudential lines on the prior constitutional review of international treaties signed by Colombia and the laws that approve them. This thesis changed a century's worth of jurisprudence from the Supreme Court of Justice, which had always been reluctant to exercise such control under the regime of the 1886 Constitution. Justice Gaona's thesis gained traction in the Court during the 1980s and was later adopted in the 1991 Constitution of Colombia (Article 241, Section 10, "Powers of the Constitutional Court," CONSTITUTION OF 1991). His most famous rulings include those on the respect for freedom of the press, the application of international treaties and human rights in Colombia, the constitutional representation and protection of minorities, the limits on police power and military criminal justice, the constitutional scope of fiscal, political, and disciplinary controls, the technique and methods of constitutional interpretation, the autonomy and independence of the judicial branch, the intermediate thesis and the constitutionality of the law approving the Extradition Treaty between Colombia and the United States of America (Law 27 of 1980), integral-type constitutional control, the constitutionality of economic emergency decrees, the state of siege and constitutional criminal law, the monetary and exchange sovereignty of the Colombian State, the constitutional regime of savings, taxes on the coffee industry, state interventionism, and economic freedoms, among others. His well-known dissenting opinion on "the Ideological Constitution," based on his study of state theory "The Doctrine of Power," has become a benchmark for methodological constitutional interpretation for Colombian and Latin American courts. It has allowed for connecting the spirit that inspires and precedes the creation of a Constitution with its normative scope, despite the distance between the time of its authors and that of its interpreters (CSJ, Dissenting Opinion of Manuel Gaona Cruz, Ruling No. 37, Case No. 868, July 6, 1981). Regarding the Ideological Constitution and the Doctrine of Power, in particular, Magistrate Manuel Gaona Cruz wrote:

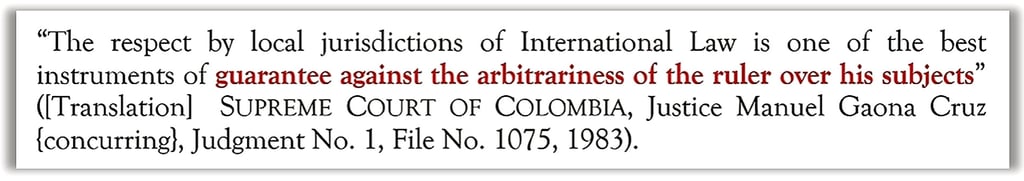

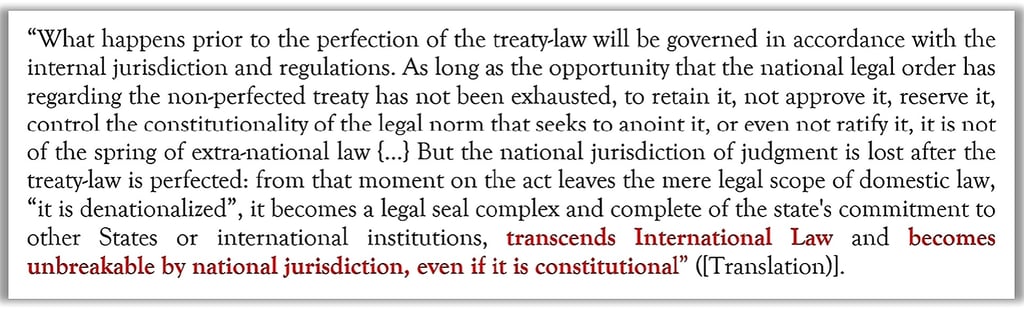

Regarding the respect for international law in Colombia and the constitutionality of the law approving the Extradition Treaty between Colombia and the United States (Law 27 of 1980), Justice Manuel Gaona Cruz wrote:

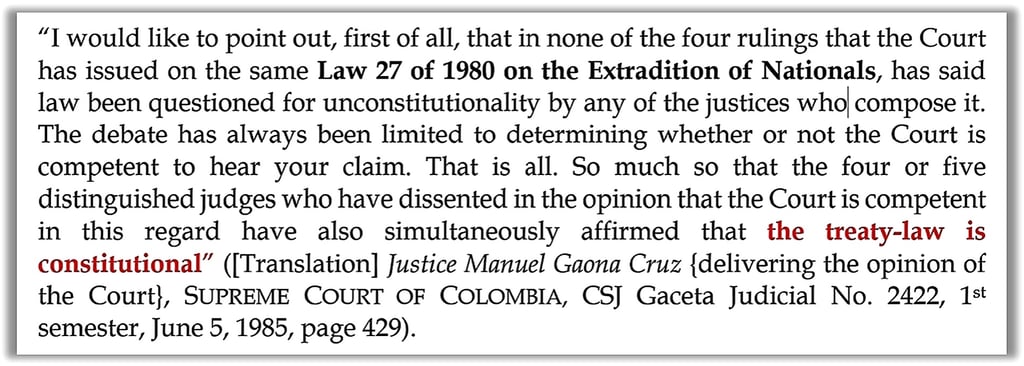

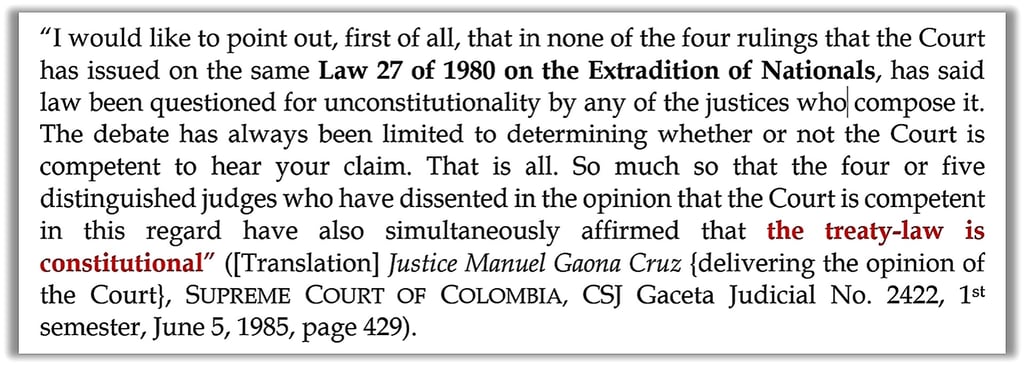

Consequently, for both the Constitutional Chamber that was deciding the fate of the law approving the Extradition Treaty between Colombia and the United States (Law 27 of 1980) and for Justice Manuel Gaona Cruz, who wrote the extradition ruling known as the "intermediate thesis," there was no doubt about the constitutionality of the treaty-law. Four months before the Palace of Justice siege, in his final intervention on the extradition of Colombian drug traffickers to the United States (CSJ, Concurring Opinion of Justice Manuel Gaona Cruz, Ruling No. 41, File No. 1275, June 5, 1985, Judicial Gazette 2422, 1st semester, page 429), thevJustice of the Constitutional Chamber of the Supreme Court of Colombia, Manuel Gaona Cruz, ruled:

The thesis of Justice Manuel Gaona Cruz on the enforceability ("ejecutoriedad") of international treaties in Colombia—including the Extradition Treaty with the United States—was called the intermediate thesis because its legal and methodological basis was built on an interpretation of both international law (general, bilateral, and comparative) and domestic law (Colombian Constitutional Law). This thesis argued that from the perspective of General International Law (Vienna Convention of 1969, articles 5 and 11), international agreements and treaties are applicable in signatory countries from the moment the treaty is perfected through the exchange of diplomatic notes between the parties. From the perspective of Bilateral International Law (United States of America and Colombia), it also established that the exchange of notes had been carried out between the Colombian Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the U.S. Department of State. According to Magistrate Gaona's meticulous analysis, the primacy of General International Law is recognized by most of the world's constitutions, which gives treaty-laws a special character and hierarchy. From the perspective of Domestic Law (Colombian Constitution), the Supreme Court of Justice only has the power of peremptory constitutional reviewover the laws that seek to approve international treaties made by the Colombian Government. This power, Justice Gaona wrote, is lost when the treaty is “denationalized” and becomes part of International Law. According to the magistrate, the denationalization of the treaty occurs when the President of the Republic signs the approving law, that is, ratifies the treaty. Once perfected and ratified, the Court loses jurisdiction to rule on the enforceability or "ejecutoriedad" of the treaty in Colombia, as it is nothing more and nothing less than an agreement that, by virtue of its perfection and ratification, ascends to a superior legal hierarchy that makes it fully constitutional: that of a treaty-law. And being constitutional, Justice Gaona added, the Court cannot do anything other than to inhibit itself, as it cannot examine the enforceability (or decree the nullity) of a treaty-law. Eventually, Justice Gaona Cruz's thesis, discussed and carefully shaped in four previous decisions with his colleagues in the Constitutional Chamber, became the official position of the Supreme Court of Justice of Colombia concerning the extradition of drug traffickers ("Colombians and foreigners") to the United States. In his constitutional study (See CSJ, Concurring Opinion of Justice Manuel Gaona Cruz, Judgment No. 1, File No. 1075, September 1, 1983), Justice Manuel Gaona Cruz wrote:

Such a jurisprudential position turned Magistrate Manuel Gaona Cruz and the Magistrates of the Constitutional Chamber into military targets for Pablo Escobar and the members of the drug cartels in Colombia. This eventually led to a criminal alliance between the M-19 guerrilla—which publicly repudiated the Court's position—and the Medellin Cartel, which, despite knowing the Court's stance, filed a nullity action through an attorney against the law approving the treaty just a few days after the Court's last ruling had declared it fully constitutional. The purpose was to use threats to pressure the magistrates of the Constitutional Chamber and their families into declaring the law “unconstitutional,” through what the Medellin Cartel called: “our declaration of war” (See MGC Death - Documentary Evidence: Pablo Escobar's Second Letter to Justice Manuel Gaona Cruz).

Jurisprudence

International Law in Colombia - Extradition Treaty between Colombia and the United States of America

Constitucional Doctrine

The Constitutional Law Attorney and the Fall of the 1979 Constitution

As a citizen and constitutional lawyer, Manuel Gaona Cruz led the group of lawyers who filed and won the unconstitutionality lawsuit (Art. 215, Constitution of 1886) against Legislative Act No. 1 of 1979, known as "The 1979 Constitution," before the Plenary Chamber of the Supreme Court of Justice. The challenged Act sought to reform the Colombian Constitution through legislative means, using as a preliminary framework temporary modifications introduced by Act No. 1 of 1977. The legal team was composed of Manuel Gaona Cruz, Antonio José Cancino, Oscar Alarcón Núñez, J. Climaco Giraldo Gomez and Tarsicio Roldán (CSJ, M.P. Fernando Uribe Restrepo, Inexequibilidad de la Reforma Constitucional de 1979, 3 de noviembre de 1981, Expediente No. 786). The scope of the reform, the unconstitutionality lawsuit against it, the Supreme Court's decision to declare it invalid, and the Legislative Decree No. 3050 of 1979—which changed the voting system (qualified majority) of the Court's Constitutional Chamber for decisions on the unconstitutionality of Legislative Acts—led to an institutional confrontation of historical proportions among the three branches of power in Colombia, in which Manuel Gaona Cruz was one of the main protagonists, given both his position as the plaintiff's lawyer and later as a newly appointed Supreme Court Justice.

From a historical perspective, the lawsuit had three major effects on the Colombian constitutional system. First, the lawsuit served as a legal precedent and a historic opportunity for the Supreme Court of Justice to establish itself as the guarantor of the protection, integrity and supremacy of the Constitution. In such process, the Court, through its decision of unenforceability and unconstitutionality, demarcated the scope of the constitutional powers of the other two branches of public power in relation to the Court's primary function: to ensure the preservation of the Colombian constitutional system.

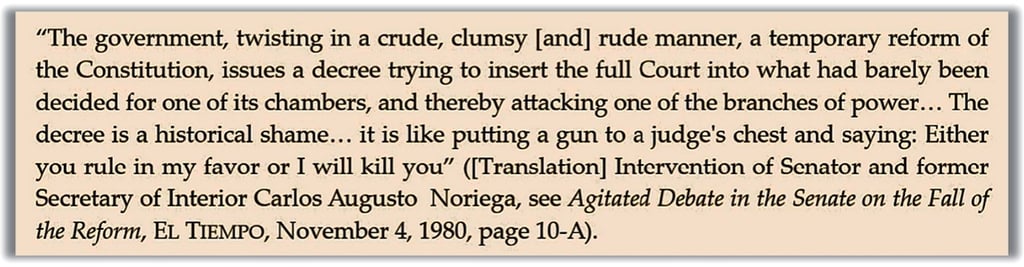

In the meantime, the Minister of Justice, Felio Andrade Manrique, announced the publication of Legislative Decree No. 3050 of 1979, which sought to nullify the Court's declaration of unconstitutionality and modify the voting system of the Constitutional Chamber. The reaction against the government's decree ("el decretazo") was immediate. Several constitutionalists of the time described the decree as "an attack on the rule of law" (Ismael Enrique Arenas, "Ilegal, el Decreto 3050," EL TIEMPO, November 10, 1980). The decree sparked a heated debate within the Congress of the Republic, where several congressmen spoke out to defend the Court's decision of unconstitutionality. In his speech, Senator and former Minister of Government Carlos Augusto Noriega summarized the actions of Minister of Justice Felio Andrade Manrique and the government of the time in the following terms:

In the midst of the debate, and just a few minutes after his first insinuation, Senator José Vicente Sánchez asked to speak in order to read a message from the leader of the opposition party at the time (the Conservative Party), former President Misael Pastrana Borrero. This message unambiguously refuted Minister Andrade's insinuation:

To prove the supposed lack of objectivity of Justice Manuel Gaona Cruz regarding the '79 reform and his criticisms of the government's Decree No. 3050, Secretary Andrade's son recorded a constitutional law class taught by Professor Gaona at the Universidad Externado (See Rubén Ordóñez Ortega, RODRIGO LARA: UN ACERCAMIENTO A SU VIDA, Figueroa Rojas Impresiones, 2005) páginas 140-141). In the recording, the professor, after a historical overview of the Separation of Powers and the role of the Supreme Court of Justice vis-a-vis the integrity of the rule of law, described the government's decision to reform the Constitution via decree and thereby to limit the Court's constitutional control as a disproportionate reaction alien to any democratic system. In that historical context, Professor Gaona warned, there would be no difference between President Turbay and General Landazábal. Judges must remain independent of political influence; such a guarantee is necessary to ensure the separation of public powers. “A closed Court is better than a submissive Court,” Professor Gaona affirmed. The defense of the Justice and the independence of the Supreme Court before Congress was led by Senators Jaime Vidal Perdomo, Luis Carlos Galán Sarmiento, Rodrigo Lara Bonilla, Guillermo Benavides Melo, and Rafael Caicedo Espinosa, who left their position on record in a written statement during the debate on the Fall of the '79 Reform, calling the government's attitude toward the Court an: "improper executive interference with the Court" (See "Acalorado debate en el Senado sobre la caída de la Reforma," EL TIEMPO, November 4, 1981, page 10-A).

The last of the three insinuations made by Secretary Andrade, according to which the modification introduced by the decree referred to the full Court and not to the Constitutional Chamber, was refuted a week later by the Council of State of Colombia in a ruling that declared Decree 3050 null and void. The council qualified its illegality as an administrative act that violated the National Constitution.

The lawsuit and the fall of the 1979 Constitution, along with the nullification of the administrative act that attempted to uphold it, remain in the annals of Colombian jurisprudence. The defense of the constitutional principle of Separation of Powers and Supremacy of the Constitution that led to the downfall of the 1979 Constitution transcended not only as constitutional doctrine in Colombia but also as a doctrinal and jurisprudential precedent in other countries (See Marisol Peña Torres, “La Caída de la Reforma Constitucional de 1979”, REVISTA CHILENA DE DERECHO, 1983, Vol. 10, pages 231-242).

In his capacity as the plaintiff against Act No. 1 of 1979, and considering, on the one hand, that the study of the constitutionality of the 1979 Reform was the responsibility of the Constitutional Chamber of the Court, and on the other hand, that by the time the case file reached the Chamber (November 1980), Manuel Gaona Cruz was already a magistrate of the Court and a member of that Chamber, the newly elected magistrate declared himself incompetent to hear the lawsuit. The Court then appointed an ad hoc judge to replace him.

Misael Pastrana Borrero President of Colombia 1970 – 1974

Despite the fall of the 1979 Constitution and the historic defeat of his Minister of Justice and his government after the rulings of unenforceability from the Supreme Court of Justice and nullity from the Council of State, President of the Republic Julio Cesar Turbay Ayala recognized the defeat as “a triumph for democracy,” stating that:

Julio Cesar Turbay Ayala President of Colombia 1978 – 1982

Felio Andrade Manrique Secretary of Justice 1980 – 1982

Carlos Augusto Noriega Senator and former Secretary of Interior 1981

Manuel Gaona Cruz Under-Secretary of Justice

Colombia Under-Secretary of Justice's request before the U.S. Departments of State and Justice Washington, D.C., 1978.

Manuel Gaona Cruz University President and Professor

Manuel Gaona Cruz Constitutional Law Attorney

Third, given the procedural failures alleged by the plaintiffs—in particular, the approval of the reform in the first round without the participation of minorities "precisely so that it would not be criticized" (See CSJ, Unconstitutionality of the 1979 Reform, ibídem, page 13) —the fall of the 1979 Constitution has become constitutional doctrine and legal precedent to ensure, since its very occurrence, the respect for the democratic participation and representation of minorities in Colombia (See Manuel Gaona Cruz and Antonio José Cancino, La Caída de la Reforma Constitucional de 1979, Ed. TEMIS, 1981)). The parts of the complaint, reiterated by the Supreme Court in its legal review, reflect the undeniable value of its doctrinal and historical significance: “The violation of the principle of minority participation determined that the incriminated law was enacted against the Constitution” (Id., page 15; files 85 and following).

Manuel Gaona Cruz Justice of the Supreme Court of Colombia 1980 - 1985

In relation to the right to the representation and constitutional protection of minorities in Colombia (CSJ, Dissenting Opinion by Justice Manuel Gaona Cruz, Judgment No. 6, File No. 993, February 10, 1983), Justice Manuel Gaona Cruz wrote:

Despite the political reactions and pressures that the fall of the 1979 Constitution produced, Manuel Gaona Cruzcontinued his work. During the half-decade he served on the Supreme Court of Justice, Manuel Gaona Cruz wrote and advanced several of the most influential judicial decisions in the Colombian legal and constitutional system.

Audio: Manuel Gaona Cruz

All rights reserved © J. Mauricio Gaona - Manuel Gaona Cruz Foundation - 2025.

The second (and most direct) effect of the trial was the downfall of the 1979 Constitution, approved by the Congress of the Republic and promoted by the Government of President Julio Cesar Turbay Ayala. This constitution contained a constitutional modification to the balance and distribution of public powers through structural changes to the powers of the legislative and judicial branches. The 74 articles that made up the 1979 Constitution sought to expand the Superior Council of the Judiciary, create the Attorney General's Office, and assign new judicial functions to the Senate, while limiting the constitutional powers of the Supreme Court in relation to the constitutional control it could exercise over government legislative decrees. The reform also modified the participation of minorities in the legislative process (composition of commissions, board of directors, voting system, etc.), the finance law, the national development plan, and the election systems for the Comptroller and the Attorney General.

In his capacity as the plaintiff against Act No. 1 of 1979, and considering, on the one hand, that the study of the constitutionality of the 1979 Reform was the responsibility of the Constitutional Chamber of the Court, and on the other hand, that by the time the case file reached the Chamber (November 1980), Manuel Gaona Cruz was already a magistrate of the Court and a member of that Chamber, the newly elected magistrate declared himself incompetent to hear the lawsuit. The Court then appointed an ad hoc judge to replace him.

To justify the government's action, Secretary of Justice Felio Andrade Manrique made three insinuations before Congress, which were quickly refuted as a prelude to the government's defeat and the declaration of nullity of Decree 3050. First, Secretary Andrade defended the decree by arguing that it was not only the result of government concerns but had also been agreed upon with the country's political leaders. Second, the Secretary suggested that the decree was necessary to counteract the attack on the legal and public order stemming from the lack of objectivity of the Justice of the Constitutional Chamber, Manuel Gaona Cruz, given his position as a plaintiff and because he had recently appeared in a Constitutional Law class to criticize the decree. And third, Secretary Andrade argued, the decree did not refer to the Court or the Constitutional Chamber but to the Supreme Court of Justice as a whole.

Secretary Andrade's attempt to get rid of Magistrate Gaona failed dramatically in a matter of hours. The next morning, after clarifying that Justice had Gaona recused himself from deciding on the lawsuit long ago, both Professor's and the Justice's voices converged in a masterful Constitutional Law lesson on the importance of the separation of public powers in modern democracies and the ethical and legal precedents supporting the distinction between the professor and the Justice. The interview ended with a resounding silence from the inquisitorial side and with the public support of the Chief Justice. After the interview and upon arriving at Externado University to teach as usual his Constitutional Law course, Professor Gaona found hundreds of students waiting for him on the stairs. Manuel Gaona Cruz couldn't even reach the classroom when, upon seeing him, a crowd of students lifted him onto their shoulders while chanting his name down the hallway of the law school to the main auditorium of the Externado University, where professors, officials, and hundreds of students were waiting to show their support. The surprise and emotion were overwhelming for Professor Gaona, who could barely express, his voice choked up, again and again: “Thank you very much, thank you all.” To commemorate the event and their professor's teachings, the graduates of the law school of Externado University of 1980 adopted the name “Class of Manuel Gaona Cruz.”

In addition to his academic background and prestige, the election of Manuel Gaona Cruz as a Justice of the Constitutional Chamber was due, in part, to his unwavering public defense of preserving the separation of powers and protecting the independence of the judicial branch. It was also due to his commitment to ensuring the constitutional representation of minorities in the legislative process and to keeping the guardianship and integrity of the Constitution in the hands of the Supreme Court of Justice.

Internationally, his theses on Latin American presidentialism and comprehensive and parallel constitutional controlin Colombia—which Professor Gaona categorized as "the most complete in the West and, therefore, in the world"(Manuel Gaona Cruz, Control y Reforma de la Constitución en Colombia, MINISTERIO DE JUSTICIA 1988, Volume II, page 72)—became doctrinal references in Comparative Constitutional Law (See Julio Cesar Ortiz, "El Control Constitucional en Colombia," BOLETÍN MEXICANO DE DERECHO COMPARADO, Universidad Autónoma de México UNAM, No. 71, 1991, pages 481-516). In Colombia, several of Manuel Gaona Cruz's rulings and theses were adopted into the 1991 Political Constitution and have transcended over time as constitutional doctrine applicable in dozens of conflicts and circumstances. The legal devotion of his work denotes his social vocation and the rigor of his constitutional judgment. Among these provisions, the following remain as judicial maxims of his legacy:

DEATH

THE ASSASSINATION OF JUSTICE MANUEL GAONA CRUZ: A CRIME AGAINST HUMANITY

I. ATTACK ON THE PALACE OF JUSTICE

II. SECURITY FAILURES AND CIVIL RESISTANCE TO THE ATTACK

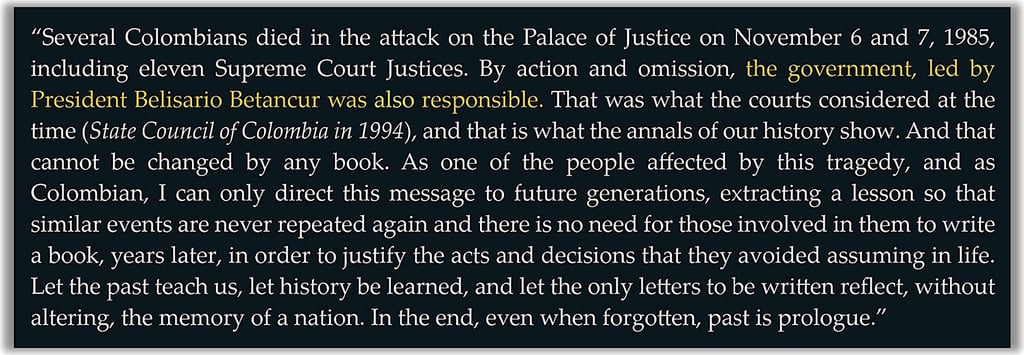

State Council, Third Division, Upholding Sentence against the State for Egregious Security Failures Sentences No. 9276 (August, 19, 1994), 9459 (April 3, 1995), 11798 (December 2, 1996).

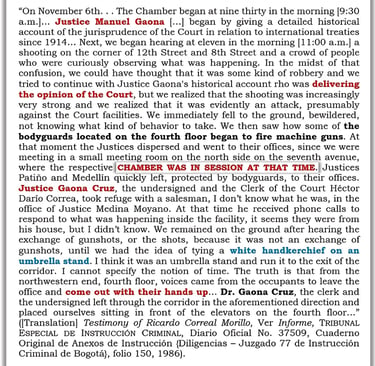

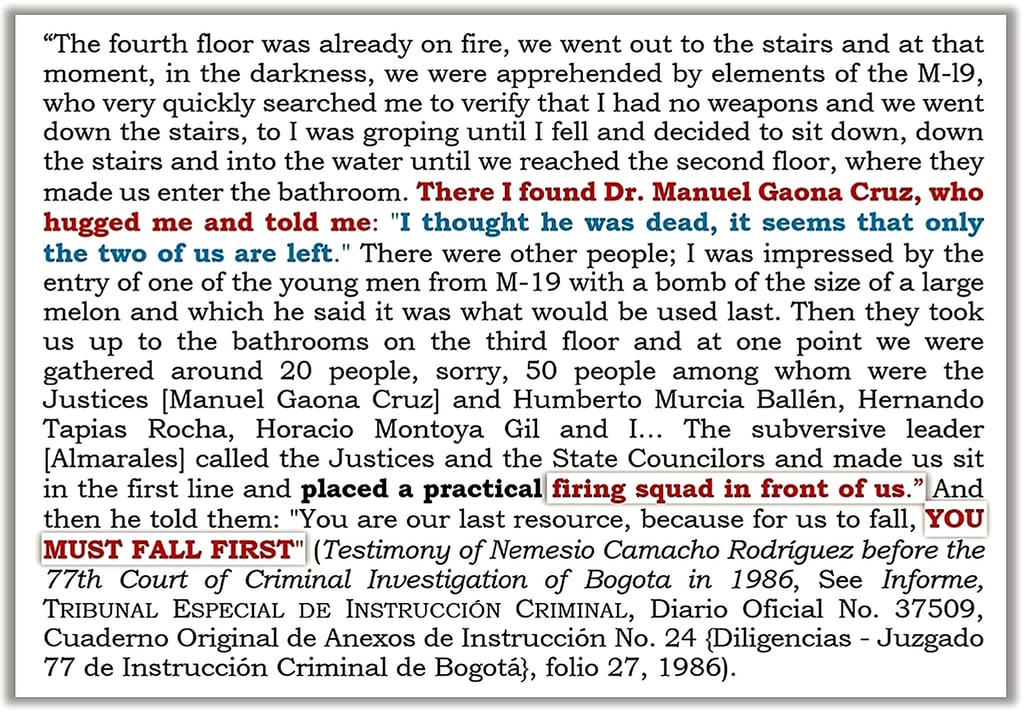

III. THE KIDNAPPING OF JUSTICE MANUEL GAONA CRUZ

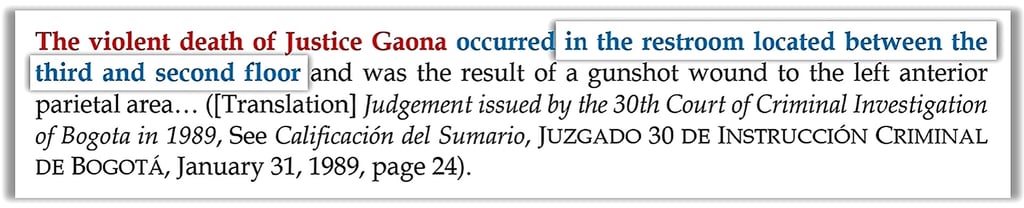

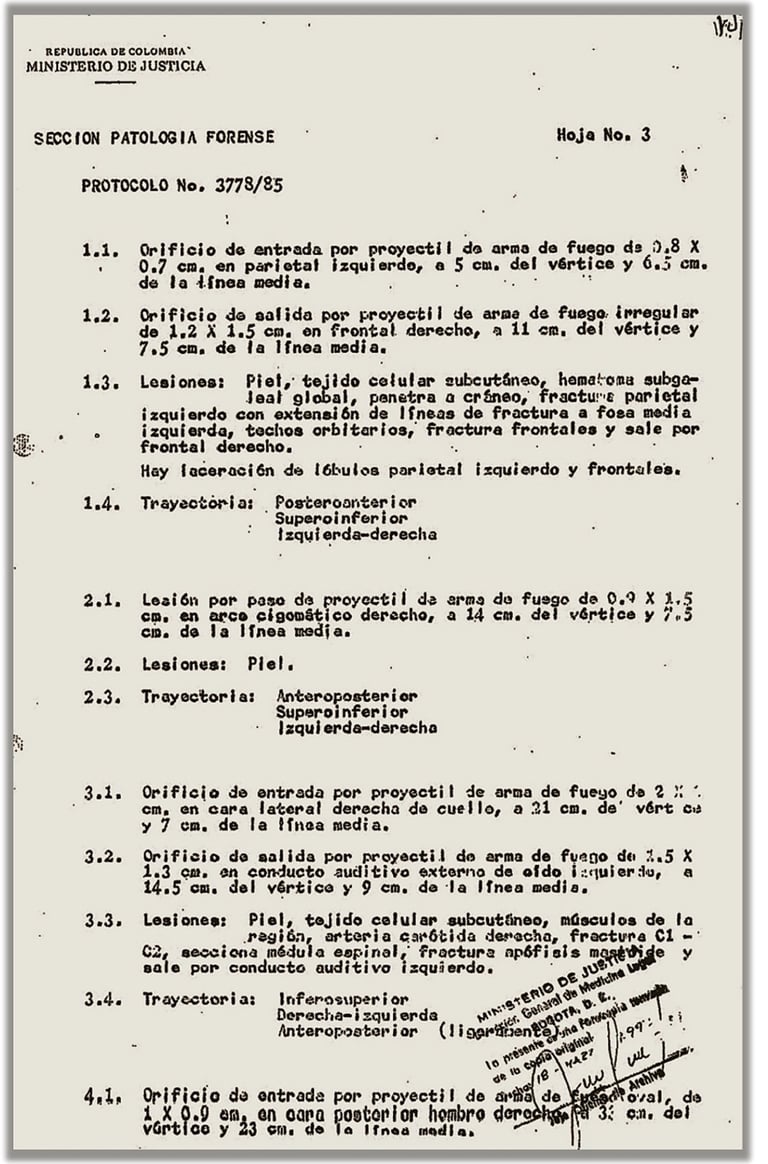

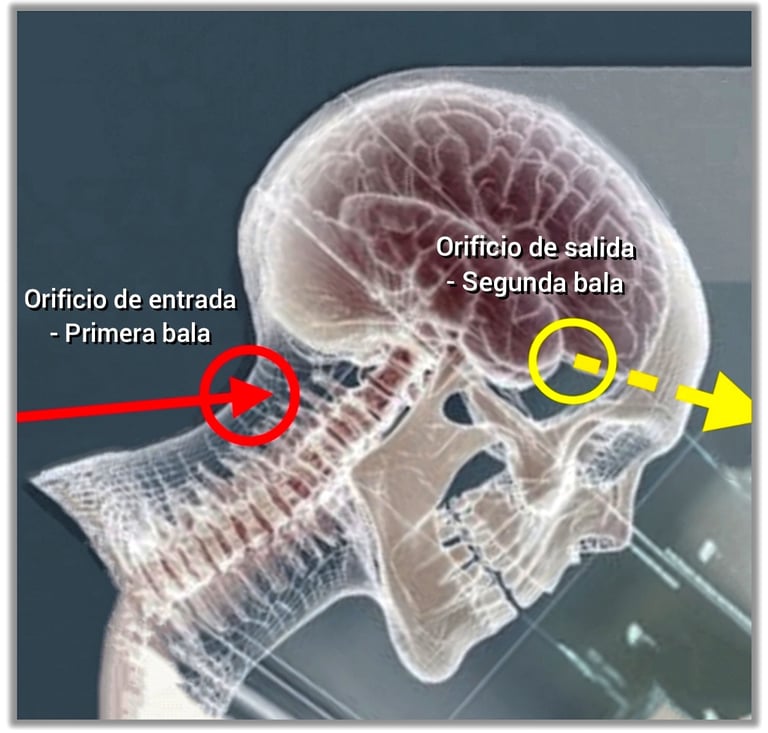

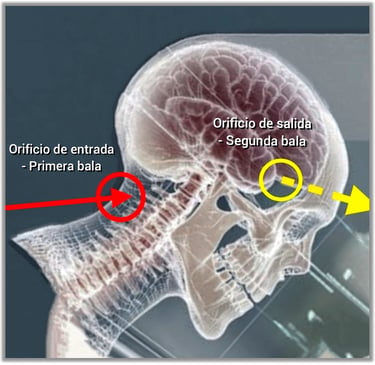

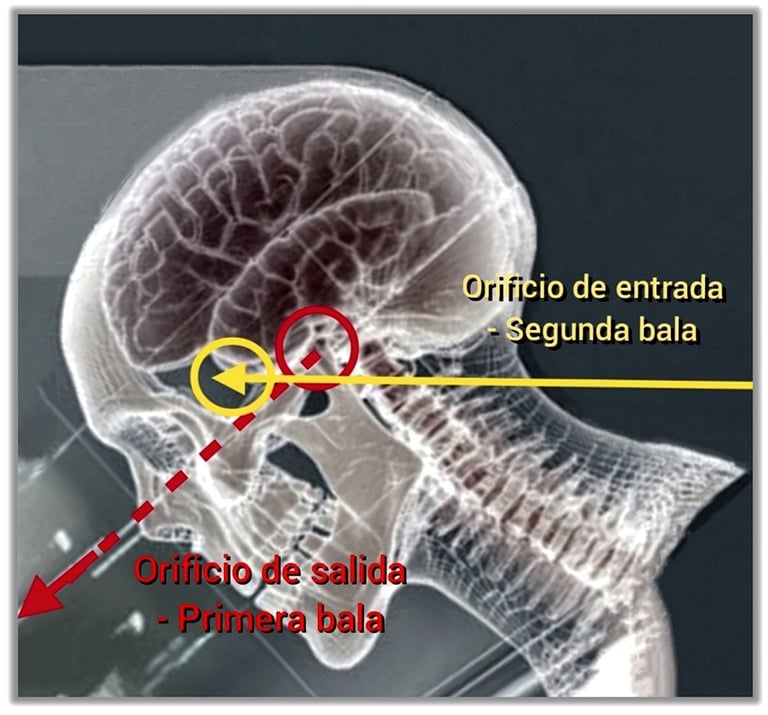

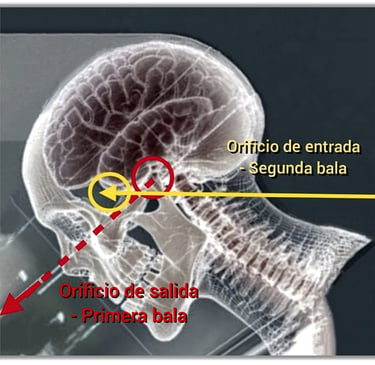

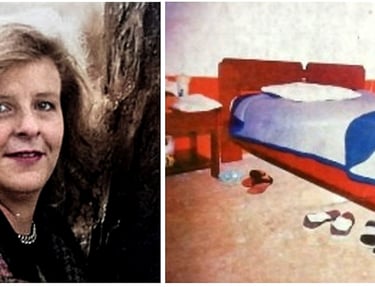

Considering, on one hand, the institutional position he held (former Chief Justice of the Constitutional Chamber and Supreme Court Justice), the legal position he supported (Justice delivering the opinion of the Court and author of the intermediate thesis that prevented the declaration of unconstitutionality of the law approving the Extradition Treaty), the circumstances that preceded his kidnapping (Justice was presenting his opinion in the day and hour of the attack), the human rights violations and the crimes against humanity he was subjected to (See MGC Death – Investigations and Responsibilities), as well as the cowardly, inhumane, atrocious, and cruel manner in which the M-19 guerrilla assassinated him (shot in the back with shots to the head after he refused to go out into the crossfire and serve as a human shield for the guerrillas who were shouting at him and pointing while Magistrate Gaona in his last words replied, “!No! We are not leaving like this. I'm not moving from here”), only to then toss his body out for the Army to see (See MGC Death – Forensic Reconstruction of the Crime Scene) and considering, on the other hand, the Army's indifference to Magistrate Gaona's request for a ceasefire and the constitutional and moral abandonment by the Government of President Belisario Betancur Cuartas, coupled with the terror instigated by Pablo Escobar in those who dared to investigate him and the need of the Government of President Barco to demobilize the M-19 guerrilla whose interests were strategically aligned with those of drug trafficking regarding extradition (See MGC Death – Documentary Evidence – Motive and Planning of the Crime: Pablo Escobar, the Extraditables and the M-19), the assassination of Justice Manuel Gaona Cruz at the hands of the M-19 became one of the most inconvenient crimes in Colombian history.